Published Jan 04, 2026 | 8:50 PM ⚊ Updated Jan 04, 2026 | 8:50 PM

The land at Nettukaltheri is officially designated for prison use, and its diversion required judicial clearance.

Synopsis: As Kerala moves swiftly to operationalise the projects cleared by the Supreme Court, the Nettukaltheri land transfer underscores a deeper policy question — how to balance strategic national priorities with the preservation of progressive correctional institutions that have served as national models.

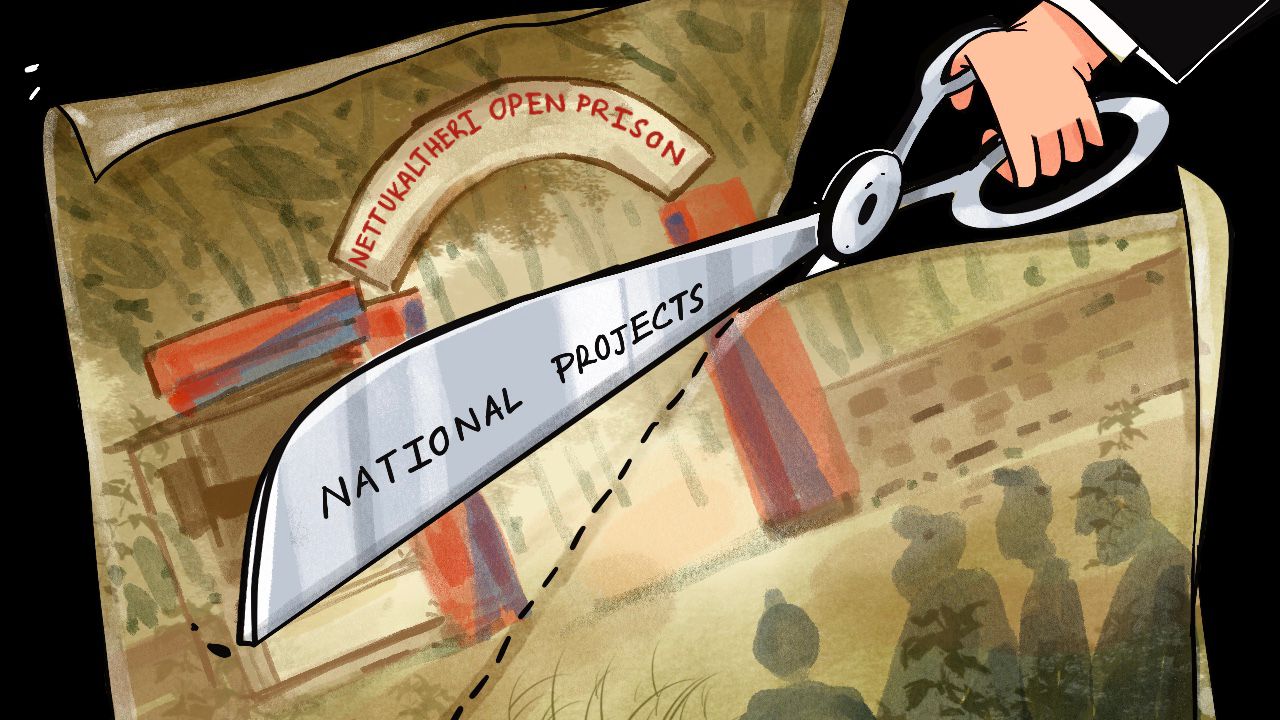

A December 2025 Supreme Court directive allowing the Kerala government to unlock a substantial portion of the Nettukaltheri Open Prison campus for strategic national projects has opened up a wider debate in the state.

The debate revolves around national security, economic growth and institutional expansion, prison reform, rehabilitation models and land-use priorities.

Following the apex court’s nod, the state can now allot 257 acres of the historic open prison at Nettukaltheri, near Kattakada, some 20 km east of the state capital Thiruvananthapuram, for three major institutions: a BrahMos missile manufacturing unit, a Sashastra Seema Bal (SSB) battalion headquarters, and a National Forensic Science University (NFSU) campus.

While the government hailed the decision as a strategic and developmental breakthrough, prison reform advocates and civil society groups raised over shrinking one of India’s most successful open prison models — and Kerala’s highest income-generating jail.

The verdict, delivered on 2 December 2025, by a Supreme Court Bench comprising justices Vikram Nath and Sandeep Mehta, cleared the state’s proposal to allot 257 acres out of the 457-acre Nettukaltheri open prison campus in Thiruvananthapuram district.

The court allowed the land to be divided as follows:

The Bench accepted the recommendations of amicus curiae, Senior Advocate K Parameshwar, who submitted a favourable report after examining the state’s proposal and the strategic importance of the projects.

In its order, the Supreme Court noted that the state had assured it would permanently retain 200 acres for the functioning of the open prison.

Open Prison & Correctional Home, Nettukaltheri.

The court observed that the proposed land transfers would not compromise prison operations, as the parcels earmarked for BATL, SSB and NFSU are physically separated from the core jail compound.

According to the amicus curiae’s report, the 180 acres sought for BATL, located in re-survey No. 66, is nearly three kilometres away from the main jail compound in re-survey No. 45/1, with private land in between.

The court also took cognisance of assurances that the new institutions would function in independent compounds and that buffer zones and wider access roads would be created to protect the retained prison area.

The Bench agreed that the land diversion was justified given the “national and security interest considerations” cited by the state.

The land at Nettukaltheri is officially designated for prison use, and its diversion required judicial clearance due to earlier court directives governing prison conditions and land use.

Such permissions are mandatory whenever land meant for jails or correctional institutions is repurposed for other public projects.

The largest share of land has been allotted to BATL, which functions under the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO).

A BrahMos missile being fired from INS Chennai during TROPEX 2017. (MoD)

According to Industries Minister P Rajeeve, the land will be used to establish a second manufacturing unit dedicated to advanced missiles and strategic defence equipment. The expansion, he said, would significantly strengthen India’s defence manufacturing ecosystem while placing Kerala firmly on the national defence-industrial map.

The project, according to government’s estimates, is expected to generate over ₹2,500 crore in GST revenue over 15 years and create more than 500 high-skilled engineering and technical jobs, apart from a substantial number of indirect employment opportunities.

Rajeev said the state had to approach the Supreme Court for approval as the land was part of a prison complex governed by earlier judicial directions. Legal opinion was sought, the Law Department consulted, and the move was approved at the highest political level before the court was approached.

The SSB battalion headquarters, to be developed on 45 acres, fulfils a long-pending request from the Union Ministry of Home Affairs.

The state government has argued that the presence of a Central Armed Police Force unit in Kerala would enhance internal security preparedness and contribute to local development.

Meanwhile, the proposed National Forensic Science University campus, spread across 32 acres, is expected to host specialised facilities such as cyber defence centres and forensic innovation hubs, offering advanced training to law enforcement agencies and high-end career opportunities for students.

Established in 1962, the Nettukaltheri Open Prison holds a unique place in India’s correctional history.

Conceived as an experiment in reformative justice, it was designed to help prisoners rebuild self-respect and dignity through agricultural work in an open environment.

The then-Home Minister, PT Chacko, had told the Assembly in the early 1960s that the prison would function without walls or barbed wire, relying instead on self-discipline.

Prisoners were engaged mainly in rubber cultivation across hundreds of acres, along with other farming activities, and were paid wages higher than those in conventional prisons.

Over the decades, the prison evolved into a sprawling correctional and agricultural complex, spread across two campuses — Nettukaltheri and the Thevancode annexe, about 8 km apart.

Together, they cover nearly 474 acres and function as a single administrative unit.

Nettukaltheri is widely regarded as Kerala’s highest income-generating jail, earning lakhs of rupees daily through rubber plantations, cattle rearing, goat farms and vegetable cultivation. Agricultural produce from the prison is regularly sold to the public through prison outlets.

At present, the open prison has an authorised capacity of 401 inmates, with 141 male convicts currently lodged there. Kerala has two other open prisons for men — at Cheemeni in Kasaragod and another women’s open prison at Poojappura in Thiruvananthapuram.

While prison officials declined to comment on the land transfer, Babu K Mathew of Prison Fellowship Kerala, an NGO working closely with inmates, said even a minor reduction in land could impact the prison’s self-sustaining farming model.

“Every inch matters for agriculture here. Farming is the backbone of the prison’s rehabilitation programme. But land scarcity is also a reality. Ultimately, this is government land, and the state has the authority to decide,” he said.

At the same time, a psychologist who works with jail inmates said, “Open prisons work because of space — physical, psychological and social. When land is reduced, it is not just acreage that shrinks but the scope for meaningful work, movement and rehabilitation.”

The psychologist further added, “Rehabilitation in an open prison is deeply linked to land availability.”

“Agriculture, outdoor work and freedom of movement are not add-ons here — they are the treatment itself. At the same time, national priorities and development needs cannot be ignored. The challenge is to ensure that expansion elsewhere does not come at the cost of the therapeutic environment that open prisons depend on,” he added.

The decision has also sparked political murmurs.

Thrissur MP and Union Minister Suresh Gopi, on 3 January, alleged that a forensic laboratory project initially proposed for Thrissur was shifted to Thiruvananthapuram after the state cited lack of land availability.

He accused the government of sidelining Thrissur in major development projects and demanded transparency in making such decisions.

As Kerala moves swiftly to operationalise the projects cleared by the Supreme Court, the Nettukaltheri land transfer underscores a deeper policy question — how to balance strategic national priorities with the preservation of progressive correctional institutions that have served as national models.

For now, the court’s approval has tipped the scales decisively in favour of security, science and industry, even as concerns linger about what the transformation means for one of India’s most celebrated experiments in prison reform.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).