Published Oct 28, 2025 | 2:00 PM ⚊ Updated Oct 28, 2025 | 2:00 PM

General Education Minister V Sivankutty said Kerala joined the PM-SHRI scheme to avoid losing about ₹1,500 crore in central aid.

Synopsis: Tamil Nadu’s case was different. It went to court seeking the release of Samagra Shikhsha Abhiyan funds, obligatory for the Centre to be provided under the Right to Education Act, and not under the National Education Policy.

A storm has been raging in the ruling Left Democratic Front (LDF) in Kerala ever since the state General Education Secretary K Vasuki signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Union Government to implement PM-SHRI on 23 October.

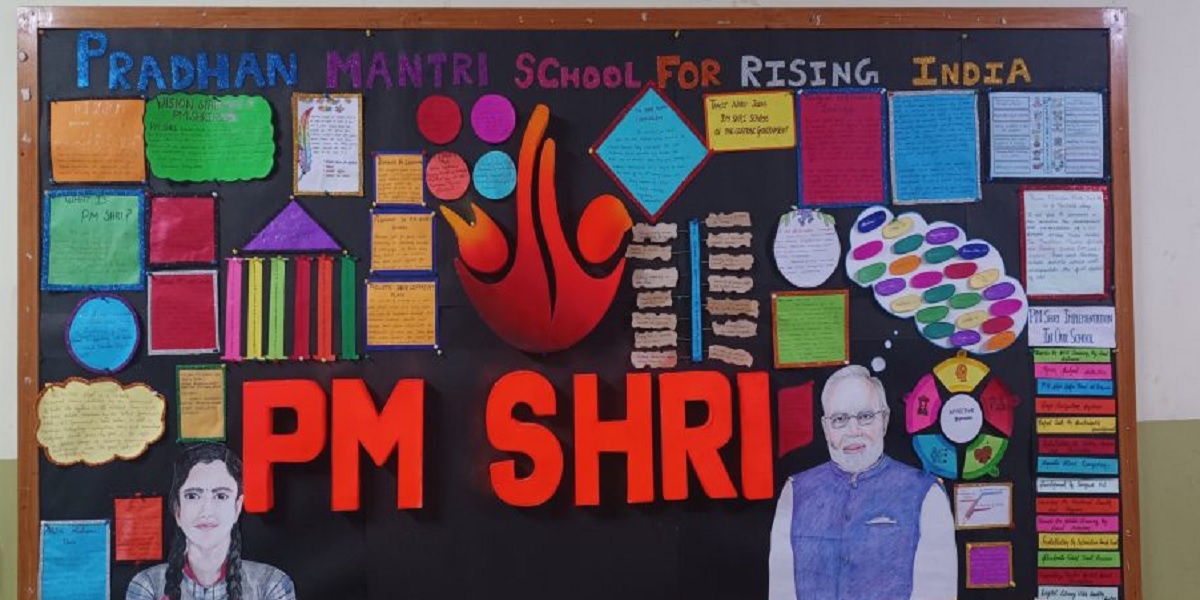

The tempest over Pradhan Mantri Schools for Rising India (PM-SHRI) has rocked the LDF, but it is unlikely to sink the ship.

The fight between the CPI and CPI(M) over PM-SHRI is no longer just about a government policy. It has now become a test of Kerala’s strength, its right to stand firm, protect its identity, and question New Delhi’s growing control.

General Education Minister V Sivankutty said the state joined the PM-SHRI scheme only to avoid losing about ₹1,500 crore in central aid. He explained that the Centre had withheld Samagra Shiksha Kerala (SSK) — a flagship central program supporting school education — funds over the state’s earlier refusal to join the scheme.

Sivankutty added that 165 schools have been selected and clarified that Kerala will continue to use its own textbooks, a concern many had expressed. It was widely feared that the PM-SHRI scheme would push Hindutva ideology in schools.

Yet, amid all the noise, a haunting question lingers: Why isn’t Kerala fighting this battle legally, as Tamil Nadu did in the Supreme Court? Behind this silence lies a web of unspoken truths, and perhaps, the real trap set by the Centre, waiting to be unravelled.

Kerala did not approach the court like Tamil Nadu over the SSK fund issue for a simple reason: Tamil Nadu’s case was different.

Under the Right to Education (RTE) Act, 2009, CBSE (including private unaided) schools must reserve 25% of their seats for children from poor and marginalised backgrounds. The fees for these students are meant to be shared between the Union and state governments in the ratio, 60:40.

When the Centre blocked Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) funds, these schools stopped getting their fee reimbursements. A collective in Tamil Nadu then approached the Madras High Court, which ruled against the state government. This meant Tamil Nadu had to pay the entire fee to these schools from its pocket.

Tamil Nadu challenged this order in the Supreme Court, arguing that the Centre had not given its 60% share as required by law. The Supreme Court found that the Centre had wrongly withheld funds, linking them to the National Education Policy (NEP), 2020, even though the RTE Act, 2009, is a law, while the NEP is only a policy.

A law is binding until it is changed or repealed, but a policy can be altered or scrapped by any government.

So, a policy cannot override a law. The law always stands higher.

In short, the money now released to Tamil Nadu is not a new grant, but the school fee that the Centre was legally bound to pay under the RTE Act.

Tamil Nadu’s petition seeking ₹2,291 crore under the SSA fund, along with 6% interest, is still pending before the Supreme Court. So far, the Tamil Nadu government has not received any money. When the state requested an urgent hearing, the Supreme Court said the case was not of an emergency nature and would be heard in the normal course.

At present, Tamil Nadu’s main concern is not about setting up the PM-SHRI Board but about the three-language policy, especially what it sees as the imposition of Hindi.

Kerala, on the other hand, has never opposed this policy.

The three-language formula was first suggested by the Kothari Commission (1964–66) and later included in the National Policy on Education, 1968. It encourages students to learn three languages — their mother tongue, Hindi or English, and a third language — to promote multilingualism and national unity.

Kerala has always followed this system. Hindi is taught in Kerala’s schools without any dispute or resistance.

Under Section 12(1)(C) of the Right to Education Act, 2009, private (CBSE) schools must reserve 25% of their seats for children from disadvantaged sections, with their fees shared between the Centre and the state. But this provision is not implemented in Kerala, because Kerala does not admit such students to private CBSE schools and pay their fees from the government treasury.

Hence, Kerala cannot file a case like Tamil Nadu demanding reimbursement of such fees.

As senior journalist Jeevan Kumar explained, Kerala’s government schools already provide excellent facilities for children from all backgrounds. Many are of international standards, with strong infrastructure, modern learning resources, and committed public investment.

Every panchayat has more than one school, and successive governments have continued to strengthen public education, ensuring that quality education is available to all, he told South First.

Supreme Court lawyer Adv. Babila Ummer Khan told South First that the SSA fund comes under the Union government’s discretionary grants as per Article 282 of the Constitution. This means the Centre can choose whether or not to give the money.

It is not a legal right of the state, and the funds are released only if the state agrees to the Centre’s terms and conditions.

In the Bhim Singh vs Union of India (2015) case, the Supreme Court confirmed that the Union government has full discretion in such matters. Because of that ruling, filing a case against the Centre to get SSA funds would be legally very difficult, with almost no chance of success.

If Tamil Nadu manages to win its case in the Supreme Court, it would be a welcome development for all states, as it could set a new precedent.

The ₹700 crore that Tamil Nadu received was not from the SSA fund; it came under the Right to Education (RTE) Act. The money reached Tamil Nadu through SSA because that is the nodal agency responsible for RTE implementation.

But the ₹2,291 crore that the Centre has withheld is linked to the NEP, which Tamil Nadu refused to approve. That case has not yet been heard in court. Even when it is, the 2015 Bhim Singh judgment gives the Centre a strong advantage, making it uncertain whether states like Tamil Nadu or Kerala could win such a case.

Kerala’s and Tamil Nadu’s issues are completely different; they arise from two separate legal and policy situations, she said.

According to public interest technologist Anivar Aravind, the PM-SHRI controversy is a symptom of a deeper, architectural shift in fiscal power.

”The key change since 2021 is that the Centre’s Public Financial Management System (PFMS) has evolved from a simple accounting and reporting tool into a powerful expenditure control platform.

Under the new “Just-in-Time” model, PFMS is no longer retrospective. It is a real-time gatekeeper. It algorithmically vets every state transaction against central compliance mandates before execution. Non-compliance results in an instant, technical denial of funds, transforming what was once a financial partnership into a permission-based hierarchy.

What is marketed as a technical upgrade for “transparency” is, in reality, a political weapon. It replaces financial autonomy with algorithmic expenditure control, recoding the federal relationship and centralising fiscal power in India” he told South First.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).