Published Dec 22, 2024 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Dec 23, 2024 | 1:21 PM

Decades-long dispute between Kerala and Tamil Nadu over Mullaperiyar Dam.(img-https://thecommunemag.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Stalin-To-Meet-Vijayan-In-Vaikom-On-Mullaperiyar-Dam-Maintenance-Issue-1024x576.jpg)

The sunflower fields stretching to the foot of the Western Ghats will take a couple more months to fully bloom. From a distance, the Vaigai Dam will offer a mystic look in chilly January mornings and evenings, a hint of fog often blanketing the reservoir.

The villages in Tamil Nadu’s Theni will unite in gratitude to a British army engineer and civil servant, responsible for providing water to the district’s fertile land and people.

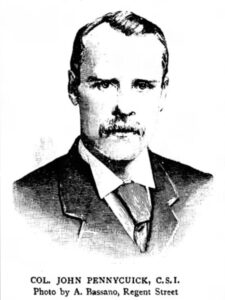

As many as 999 hearths will crackle to life in January, as people reverently offer Pennycuick Pongal to Colonel John Pennycuick (1841-1911), who designed and constructed the Mullaperiyar dam at Idukki in Kerala. The dam provides water to several districts in Tamil Nadu.

The Mullaperiyar dam has turned the dry lands of Theni, Madurai, Dindigul, Sivagangai, and Ramanathapuram into fertile havens of prosperity. Even today, generations honor Pennycuick not only through the Pongal festival but also by naming their children after him, a testament to the enduring bond between a visionary and the lives he had touched.

The dam’s story is about emotions, forged documents, political drama, and a long-standing conflict between two neighboring states, Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

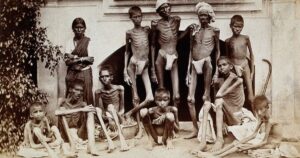

Parts of the erstwhile kingdom of Travancore faced devastating floods between 1876 and 1878, while regions under the Madras Presidency suffered from a severe famine that claimed over 1 million lives. The Periyar and Vaigai rivers, both originating from the Western Ghats, were significantly affected by these events.

Col John Pennycuick. (Wikimedia Commons)

During the summer, the Vaigai River would often dry up before reaching Madurai, exacerbating the drought that followed the famine and continuing to take lives in the Madras Presidency. Meanwhile, in parts of Kerala, particularly Travancore, heavy rains and floods led to further loss of life.

This dire situation inspired the British colonial administration to consider the construction of a dam across the Periyar River. In 1882, Colonel John Pennycuick’s design, which combined rubble and concrete, was selected after several revised plans.

Construction of the dam commenced in May 1887 and was completed in 1895. The dam was officially inaugurated on 10 October 1895.

The location chosen for the dam was originally under the jurisdiction of the Travancore kingdom. When the British rulers sought to construct the dam, they required permission from King Vishakam Thirunal Ramavarma of Travancore.

Madras famine of 1876.(Wikimedia Commons/Wellcome Library Image Catalogue)

The British were confident that they would obtain the permission, as in earlier years, the British army had assisted Travancore in warding off Tipu Sultan’s invasion bids. However, the king did not consent to the agreement without a price.

The British government justified the deal by claiming that the waters of the Periyar were of no real value to Travancore, as the surrounding areas were largely uninhabited forests. However, after over 10 years of resistance, the Maharaja eventually signed the lease agreement.

In a powerful expression of his reluctance, King Vishakam Thirunal Ramavarma declared, “I am signing this agreement with my blood!” His words reflected not only the deep personal anguish over the concession but also the weight of a decision made under considerable pressure.

Periyar lease agreement.

On 29 October 1886, a lease agreement was established between Maharaja Vishakam Thirunal Ramavarma and the Secretary of State for India, concerning the Periyar irrigation project.

The agreement included the lease of 8,000 acres, located 155 feet above the Periyar water level, along with an additional 100 acres to the then-Madras government. This lease granted the British the right to divert water from approximately 648 square kilometers of the Periyar basin above the dam for use in the Madras state.

In return, Travancore was to receive an annual lease payment of ₹40,000, calculated at five rupees per acre. This lease amount was deducted from the tax Travancore owed to the British. The agreement stipulated a lease term of 999 years, with the possibility of renewal for another 999 years.

The dam, located at 9º 32’ 0” N latitude and 77º 8’30” E longitude, now stands in the Peermedu taluk of Idukki district.

Colonel Pennycuick identified the location for the dam at the place where the Periyar and Mulla rivers converge, eventually forming the Mullaperiyar River. After flowing for 11 kilometers, the river passes between two mountains, creating a natural pathway for the dam.

A view of the Mullaperiyar Dam. (Creative Commons)

The Mullaperiyar Dam is a gravity dam, meaning it relies on the sheer weight of its structure to resist the pressure exerted by the water.

At one point, the Madras Presidency nearly abandoned the project due to the persistent challenges of floods, landslides, and the spread of diseases. Despite this, Pennycuick remained determined. He returned to England, sold his assets, and used the proceeds to fund the completion of the dam, ultimately ensuring its successful construction.

Mullaperiyar Dam is made of surkhi mix instead of concrete. Surkhi is a traditional building material used in India, made by combining lime with burnt clay, brick dust, or powdered bricks.

The Mullaperiyar Dam’s catchment area lies entirely within Kerala, making it an intrastate river. On 21 November 2014, the dam’s water level reached 142 feet for the first time in 35 years, and again on 15 August 2018, following heavy rains in Kerala.

Kerala has consistently criticised the 1886 leasing agreement and challenged its legality, particularly highlighting concerns over the safety of the 126-year-old dam. Discussions regarding the dam’s potential failure have been ongoing since 2009.

Tamil Nadu has opposed Kerala’s proposal to decommission the dam and construct a new one.

A major point of contention is the dam’s rule curve, which regulates reservoir storage levels, the timing of gate openings, and overall safety measures.

Kerala has raised concerns over Tamil Nadu’s outdated operational schedule and the lack of access to vital data due to terrain challenges and inadequate infrastructure.

In 2006, the Supreme Court allowed the water level of the Mullaperiyar Dam to be raised to 142 feet, contingent on the completion of reinforcing measures, additional vents, and other safety proposals.

Kerala, while agreeing to provide water to Tamil Nadu, expressed concerns about the dam’s safety due to its age, and the risk posed by potential leaks.

In 2014, the Supreme Court ruled the Kerala Irrigation and Water Conservation (Amendment) Act, 2006, invalid, paving the way for Tamil Nadu to increase the water level to 142 feet. A permanent Supervisory Committee was established to address safety issues.

However, a UN report highlighted the dam’s vulnerabilities, noting that its location in a seismically active area and its age pose significant risks, with an estimated 5 million people potentially affected if the dam were to fail.

The Supreme Court allowed Tamil Nadu to raise the water level of the Mullaperiyar Dam, citing the state’s significant efforts in maintaining and strengthening the dam.

On 21 November 2014, the dam’s water level reached 142 feet for the first time in 35 years, and again on 15 August 2018, following heavy rains in Kerala.

Tamil Nadu government invested heavily, spending nearly ₹26 crores on essential enhancements, such as establishing an ice plant at Mullaperiyar for mass concreting. Ice cubes are used during concreting to prevent excessive pressure buildup.

On the other hand, Kerala’s argument centered around the potential risks associated with the dam, including findings from a dam break analysis conducted by IIT-Roorkee. The study highlighted threats from heavy rainfall, earthquakes, and shockwaves caused by landslides, emphasizing the possibility of catastrophic failure during a hydrological event.

Despite submitting these concerns, the Supreme Court questioned Kerala’s stance, pointing out that in the event of a seismic event measuring six on the Richter scale, even the Idukki arch dam would likely be the first to suffer damage, not the Mullaperiyar Dam.

While Tamil Nadu demonstrated its consistent efforts and presented the strengthening measures convincingly, Kerala fell short in advocating for the decommissioning of the dam. This disparity in arguments ultimately influenced the court’s decision in favor of Tamil Nadu.

Over the years, Tamil Nadu’s political parties have used the Mullaperiyar Dam issue to sway voters.

DMK leaders, including M Karunanidhi in 2014 and MK Stalin in 2019, promised in their election manifestos to raise the dam’s water level to 152 feet, a demand recently reiterated by Minister TN Periyasamy.

Similarly, the AIADMK under Jayalalithaa celebrated a Supreme Court verdict permitting increased water storage as a major political victory. Both parties have politicised the emotional connection of Tamil Nadu’s people to the dam, sidelining Kerala’s safety concerns.

Currently, Tamil Nadu diverts the dam’s water for agriculture and drinking needs across five districts. Recently, Kerala granted Tamil Nadu permission for essential repairs following discussions between Chief Ministers Stalin and Pinarayi Vijayan at Vaikom.

This approval, surprisingly issued before Stalin formally raised the request, marked a temporary shift in Kerala’s earlier stance of prioritising safety guarantees.

As for the 999 hearths that would be lit to make pongal in January — the number refers to the lease period.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).