Published Feb 08, 2026 | 1:23 PM ⚊ Updated Feb 08, 2026 | 1:23 PM

Representational image. Credit: iStock

Synopsis: Kerala’s government has introduced special incentives and restrictions for postings in the neglected districts of Kasaragod, Idukki, and Wayanad. Service in these areas now counts double for transfers, offering priority relocation afterward, while imposing strict limits on leave, transfers, and deputations to curb chronic vacancies and ensure administrative continuity in geographically isolated, development-lagging regions.

On paper, a government posting comes with no geography clauses. In terms of Kerala, from Kasaragod to Thiruvananthapuram, the state is supposed to be one seamless administrative unit.

However for years, that unwritten rule has stopped short at the borders of Kasaragod, Idukki, and Wayanad.

These three districts have existed in an awkward administrative blind spot: officially part of the state’s routine posting cycle, yet quietly treated as exceptions.

Vacancies linger there longer, officers find ways out faster, and development projects move at a crawl.

Now, the government has chosen to confront this imbalance — not by enforcing the original service compact, but by rewriting it.

Through a mix of incentives, restrictions and special exemptions, postings to these districts are being repackaged as both a reward and a restraint.

However, this sweetening also raises some uncomfortable questions – why have three districts come to require a special rulebook of perks and penalties? And what does it say about a system that must bargain with its own employees to deliver basic governance where it is needed most?

When the state government framed uniform norms for transfers and postings, it was meant to ensure fairness and predictability across departments.

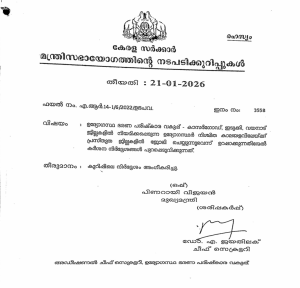

But an order issued on 22 January by Additional Chief Secretary Rajan N Khobragade of the Personnel and Administrative Reforms Department shows how those rules are now being consciously relaxed — and reshaped — for three districts alone: Kasaragod, Idukki and Wayanad.

At the heart of the move is a long-standing problem the government has struggled to solve — a persistent reluctance among employees to serve in these districts, resulting in chronic vacancies and repeated disruptions to flagship development packages.

The latest instructions are not a sudden deviation.

They are the outcome of years of review meetings, including discussions chaired by the Additional Chief Secretary for Planning and Economic Affairs, and separate consultations involving the Chief Secretary and the Kasaragod District Panchayat President.

Across departments, the diagnosis has been the same: projects stall because sanctioned posts remain vacant, officers seek transfers at the first opportunity, or prolonged leave weakens already thin administrative capacity.

To counter this, the government has decided to use incentives — and restrictions. One of the most significant relaxations is in how service tenure is counted. For transfer purposes, one year of service in Kasaragod, Idukki or Wayanad will now be treated as equivalent to two years in other districts.

Officials who complete the mandatory tenure will also be given first preference when seeking transfers to districts of their choice later.

At the same time, the government has drawn clear red lines.

Employees posted to these districts for compulsory service cannot dilute their tenure through long, non-medical leave; any excess leave will simply extend their stay.

Those appointed through district-level PSC notifications after opting for these districts will be barred from deputation, transfer or mutual transfer for at least 10 years — a condition proposed to be built directly into future PSC notifications, backed by consent letters at the time of joining.

The logic, the order says, is twofold.

First, ensure continuity in administration where terrain, distance and limited infrastructure already make governance difficult.

Second, create real opportunities for local candidates, who are more likely to stay back and serve without repeatedly seeking exits.

An excerpt from the Cabinet notes which approves the relaxations

The order also proposes restricting promotions of district-level recruits to posts within the same districts, subject to vacancy, and tightening leave provisions to prevent the practice of “posting without presence”.

Only unavoidable medical leave would be entertained.

Interestingly, the government has also opened a door for those who genuinely wish to build long careers in these districts.

Employees willing to continue beyond three years can do so with written consent, with the possibility of later postings within nearby stations of the same district. Senior officers can even be brought back to these districts after stints elsewhere, again subject to vacancy and consent.

Taken together, the exemptions underline an uncomfortable reality: uniform rules have not worked uniformly on the ground.

For Kasaragod, Idukki, and Wayanad — districts marked by geographical isolation, development lag and staffing fatigue — the government has chosen carrot over stick, and it got the backing of a Cabinet meeting decision on 21 January.

A note circulated to the Council of Ministers on 21 January during the Cabinet meeting, accessed by South First, lays out the ground realities that compelled the government to allow relaxations in these three districts.

The document traces the policy back to a high-level review meeting held on 22 November, 2021, chaired by the Additional Chief Secretary (Planning and Economic Affairs), which examined the functioning of the special development packages for Kasaragod, Idukki, and Wayanad.

The meeting concluded that frequent transfers were severely affecting project implementation in these backward and geographically challenging districts.

To address this, departments were directed to identify suitable officials for package implementation and ensure that officers posted in the three districts continue for a project-specific minimum tenure.

These directions were later formalised through a circular issued on 14 March, 2022, with strict instructions to department heads to incorporate tenure conditions in appointment orders.

The urgency behind the relaxations became clearer during a subsequent meeting on 8 March, 2022, focused on the Kasaragod Development Package.

The Chief Secretary and the Kasaragod District Panchayat president flagged widespread staff vacancies across departments, warning that development works were stalling for want of personnel.

Adding to the pressure, the Kerala State Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Commission recommended district-specific recruitment, including a proposal to earmark at least 50 percent of posts for Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe candidates from the respective districts through a special legal mechanism.

These concerns were escalated to the Chief Minister, who directed the Chief Secretary to hold consultations with service organisations and submit a detailed view.

The exemptions, the note suggests, were not administrative favours but stopgap measures aimed at retaining officials, ensuring continuity and addressing structural imbalances in districts that have historically lagged behind the rest of the state.

Finance warns leave rule change could hit state exchequer hard

While broadly backing the government’s move to make compulsory postings in Idukki, Wayanad and Kasaragod more attractive, the Finance Department has raised strong objections to a proposal that it says could open the door to heavy and unpredictable expenditure.

In a note submitted to the government in 2024, the department flagged one specific clause in the original proposal — a plan to revise the rate of earning earned leave from one day for every 11 days of service to one day for every eight days for employees serving in the three districts.

The Finance Department said it was unable to agree with this change.

Under existing rules, an employee with 30 years of service earns around 990 days of earned leave, though up to 1,200 days can be surrendered.

Reducing the qualifying period to eight days, it warned, would substantially increase the leave accumulated.

When surrendered, this additional leave would translate into a major financial liability for the government, the scale of which cannot be accurately estimated in advance.

The department also cautioned that region-specific leave rules would dilute the uniformity of the Kerala Service Rules (KSR) and complicate leave accounting, especially with frequent transfers.

As an alternative, it suggested giving additional transfer weightage for service in the three districts — such as counting one year there as two elsewhere — a proposal that was later approved.

The Personnel and Administrative Reforms Department said it had no specific comments, noting that leave matters fall under the KSR.

Blessed with forests, hills and postcard landscapes, Kasaragod, Wayanad and Idukki should, on paper, be among Kerala’s most desirable districts.

In reality, they have for decades remained the most difficult postings for government officials across departments — places many arrive at reluctantly and leave at the earliest opportunity.

The result is a chronic cycle of vacancies that quietly erodes governance and development.

The primary deterrent, officials say, is geography — relentless and unforgiving.

“Kasaragod still feels like a different state administratively,” said a senior Revenue officer who has served there twice. “You are nearly 600 km from Thiruvananthapuram. Every meeting, every file movement, every training programme comes with travel fatigue built in.”

Wayanad and Idukki present a different challenge.

Hemmed in by forest terrain and narrow ghat roads, both districts become vulnerable during the monsoon, when landslides and road closures can cut off entire taluks for days.

The absence of rail connectivity only deepens the sense of isolation.

“There are weeks during heavy rains when you are simply stuck,” said an Assistant Engineer posted in Idukki to South First. “If a road goes, everything goes with it — inspections, school visits, even basic administration.”

Healthcare, officials say, is a quieter but decisive factor.

Despite improvements, Kasaragod continues to be perceived as dependent on hospitals in Mangaluru for tertiary care — a perception that shapes family decisions even today.

In Wayanad and Idukki, the shortage of specialist doctors feeds a constant anxiety, especially among officers with young children or elderly parents.

“It’s not about luxury,” said a woman officer posted in Wayanad. “It’s about knowing that in an emergency, help is close. Here, that certainty doesn’t exist.”

Professionally too, the districts offer little visibility.

With vacancies often touching 30–40 percent in key departments such as Revenue, Education and Health, officers find themselves managing disproportionate workloads.

Yet the assignments that bring policy exposure or career leverage remain concentrated in urban centres.

“You work more, but your work is seen less,” said a mid-career official in Kasaragod. “That creates frustration over time.”

Slowly, a stigma has attached itself to these postings — the unspoken label of a “punishment transfer”.

No one admits to it openly, but the sentiment is widespread.

Family considerations often seal the reluctance.

Limited options for higher education, fewer private-sector jobs for spouses, and concerns around safety in remote areas weigh heavily, particularly on younger officers and women employees.

“As officers, we don’t fear work,” said a senior official in the high ranges. “But when infrastructure is weak and vacancies are routine, the system sets you up to fail. And that fear is what people really want to avoid.”

Until these structural issues are addressed — through incentives, better connectivity and visible career support — Kerala’s most scenic districts may continue to be its most administratively neglected.

(Edited by Amit Vasudev)