The latest spark came from Tirur MLA Kurikkoli Moideen, who demanded the formation of a new “Tirur district,” citing developmental neglect in the coastal and central parts of Malappuram.

Published Oct 06, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Oct 06, 2025 | 9:00 AM

Malappuram — literally, the land atop the hills — has an estimated population of 4.9 to 5 million. Pictured, Areekode in Malappuram. (Creative Commons)

Synopsis: The long-standing demand for bifurcating Malappuram — Kerala’s most populous district — has been raised once again, as the state is heading toward local body and Assembly polls. Formed in 1969, the district has often been painted in communal hues, mostly by the right-wing, pro-Hindutva groups. This report traces the developments that led to the formation of the Malappuram district and the demand to bifurcate it.

As Kerala inches closer to local body and Assembly elections, an old demand has resurfaced with renewed vigour: The bifurcation of Malappuram, the state’s most populous district.

What began decades ago as a call for better governance, streamlined administration, and fairer distribution of resources is once again back in the spotlight, reviving memories of the district’s birth in 1969 and sparking fresh debates among parties eager to woo voters in this Muslim-majority stronghold.

Tirur MLA Kurukkoli Moideen has once again brought the demand for bifurcating Malappuram district into the spotlight.

Tirur MLA Kurukkoli Moideen at the Revenue Assembly in August.

Speaking at the Revenue Assembly convened at the Institute of Land and Disaster Management, Thiruvananthapuram, Moideen urged the government to create a new district with Tirur as its headquarters.

He proposed that the new district include Tirur, Tirurangadi, and Ponnani taluks—coastal regions largely inhabited by fishermen and other communities that he said remain economically and socially backward.

Moideen argued that Malappuram, despite being the most populous district in Kerala, lags in adequate access to government services, and its bifurcation would ensure better governance and delivery.

The MLA has raised the same demand earlier. In 2021, at his first press meet after being elected as the UDF candidate from Tirur, he pledged to raise the demand for a Tirur district in the Assembly.

The revival of this call has not only reopened discussions on whether the time has come for another administrative division but also casts a fresh spotlight on the historic establishment of Malappuram district in 1969.

“Malappuram” — literally, the land atop the hills — officially came into being on 16 June 1969, carved out from portions of the erstwhile Kozhikode and Palakkad districts.

EMS Namboodiripad

Yet, its formation was far from a simple act of administrative reorganisation.

It triggered one of the most intense political and communal debates in Kerala’s history. Critics branded it “Mappilastan” or “Mopalstan” — a derisive reference likening it to the Muslim majority and thereby Pakistan. Supporters hailed it as long-overdue justice for a backward region.

The idea of a separate revenue district for the backward Eranad and Valluvanad taluks had first been raised in 1960 by P Abdul Majeed, a Muslim League MLA. He and others argued that the hilly Malabar interior suffered from economic neglect and administrative inefficiency under Kozhikode and Palakkad.

Despite sporadic demands, the issue did not gain traction until the 1968 state conference of the Indian Union Muslim League (IUML) held in Kozhikode, which adopted a formal resolution demanding the creation of the Malappuram district.

The demand soon became politically charged.

Malappuram.

While proponents emphasised development and governance, opponents accused the League of seeking a “communal homeland” for Muslims in Kerala’s Malabar region — a claim that would dominate political discourse for years.

Kerala’s political scene in the late 1960s was marked by an experiment in coalition politics. The 1967 elections brought to power the United Front government, a seven-party alliance (Sapthakakshi Munnani) led by Chief Minister EMS Namboodiripad of the CPI(M).

The coalition included the CPI, Muslim League, RSP, Samyuktha Socialist Party, Karshaka Thozhilali Party, and the Kerala Socialist Party.

Within this political framework, the Muslim League’s support was crucial for the survival of the EMS government.

Critics later alleged that the creation of Malappuram was a “reward” for that political backing. However, CPI(M) leaders, including EMS himself, maintained that the decision was purely administrative and aimed at addressing regional backwardness.

On 5 May 1969, the government, acting on the recommendations of AN Kaleeswaran, the Special Officer appointed for the purpose, and the report of a Cabinet Sub-Committee comprising EMS, KR Gouri (Revenue Minister), and CH Muhammad Koya (Education Minister), approved the formation of the new district.

Earlier, when questioned in the Assembly on 22 January 1968, Revenue Minister Gouri clarified that no official proposal had been received from the Muslim League party for forming such a district.

However, she acknowledged that the government had received petitions from “several public organisations and institutions,” some of which had Muslim League leaders as their committee members.

Despite these clarifications, opposition parties — notably the Congress and the Jan Sangh — launched strong campaigns against the proposal. The Jan Sangh released a pamphlet titled “Malappuram or Mopalstan?”, portraying the move as an act of communal appeasement.

Question to Revenue Minister K.R. Gouri on 22 January 1968 regarding Malappuram.

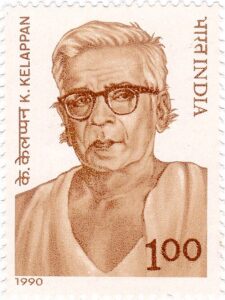

Among those who took a firm stand against the district formation was K Kelappan, the revered Gandhian leader of the freedom struggle. He spearheaded the anti-district committee, warning that creating a district on communal lines would reopen the wounds of Partition.

Kelappan’s supporters argued that he was not opposed to the development of Malappuram but to what he saw as the dangerous mixing of religion and governance.

On the day of Malappuram’s inauguration, protests led by Kelappan — and joined by Jan Sangh’s national leaders — were held at the district headquarters.

In the midst of this heated atmosphere, AK Gopalan (AKG), then CPI(M) state secretary and once a close associate of Kelappan, published an open letter addressed to “My dear Kelappettan,” defending the government’s decision as a step toward rectifying the historical neglect of a backward region.

Kelappan, in turn, responded through the press, addressing AKG as “My dear younger brother” and asserting that while he supported every measure for the area’s progress, he would oppose anything that risked dividing people along communal lines.

Gandhian K Kelappan.

Despite fierce opposition, Malappuram district came into existence on 16 June 1969, comprising the Eranad and parts of Tirur taluks from Kozhikode and portions of Perinthalmanna and Ponnani taluks from Palakkad.

Though the government that gave birth to Malappuram fell, the district survives.

It is also interesting to recall that the idea of forming Malappuram district — today one of Kerala’s most prominent regions — once sparked heated discussions in Parliament.

On 25 July 1969, a group of MPs questioned the then Minister of State for Home Affairs, Vidya Charan Shukla, about Kerala’s move to create a new district called Malappuram, carved out of parts of Palakkad and Kozhikode.

The MPs wanted to know whether it was true that the proposed district would have a Muslim majority, and if it was also a fact that the Jan Sangh, Congress, and other national leaders were opposing its formation. They also asked whether the Union government had written to the Kerala government on the issue, and what the state’s response had been.

On 25 July 1969, a group of MPs questioned the then Minister of State for Home Affairs, Vidya Charan Shukla on the formation of Malappuram.

In reply, Minister Shukla informed the House that, according to the information received from the Kerala government, Malappuram district had indeed been formed — purely for administrative reasons, with no communal considerations involved.

He further added that the only organised political opposition came from the Jan Sangh, while a parallel “anti-Malappuram agitation” was being led by Sarvodaya leader K Kelappan.

The minister clarified that the Centre had not corresponded with the State government on the matter.

Over time, the “Mappilastan” slur faded, only to pop up intermittently in right-wing social media groups. Now, with the demand for bifurcation coming up again, the age-old allegations are also back.

The long-standing debate over bifurcating Malappuram district has resurfaced once again, stirring political ripples across Kerala’s most populous region.

The latest spark came from Tirur MLA Kurikkoli Moideen, who demanded the formation of a new “Tirur district,” citing developmental neglect in the coastal and central parts of Malappuram.

However, the Indian Union Muslim League (IUML) swiftly distanced itself from Moideen’s statement.

Party state general secretary PMA Salam clarified that the League had neither discussed nor decided on any proposal to divide Malappuram, describing Moideen’s remarks as his personal opinion.

The controversy gained traction after Moideen raised the issue during the district revenue assembly held in Malappuram, prompting a sharp response from LDF MLA KT Jaleel, who challenged whether the UDF would dare include such a proposal in its election manifesto.

When Malappuram was carved out in 1969, it comprised just four taluks — Eranad, Perinthalmanna, Tirur, and Ponnani — and had a population of around 1.4 million.

Over the decades, the district has expanded to seven taluks, 138 villages, 15 block panchayats, 94 grama panchayats, and 12 municipalities, represented by 16 Assembly constituencies.

By 2025, its population is estimated to have crossed 4.9 to 5 million, making it Kerala’s most populous district.

The sheer density, it’s alleged, strains infrastructure and public services, fueling periodic demands for bifurcation to ensure more balanced governance and resource allocation.

Proposals to divide Malappuram have been raised repeatedly since the 1970s, often intersecting with issues of development, communal harmony, and regional identity.

In 2010–2013, the Social Democratic Party of India (SDPI) spearheaded a formal agitation, including a district-wide hartal in 2013, demanding a new district comprising Tirur, Tirurangadi, and Ponnani.

The IUML briefly echoed support, but then Chief Minister Oommen Chandy ruled it out.

Then in 2015, the Malappuram District Panchayat passed a resolution urging the government to consider bifurcation for equitable development. In 2019, IUML MLA KNA Khader moved a calling attention motion in the Kerala Assembly, later withdrawn following controversy.

Kerala Congress (Mani) floated an alternative proposal for an “Edappal district.” In 2021, the Kerala Muslim Jamaat petitioned the collector to restructure taluks and villages, citing population growth since 1969.

The demand took a sharper turn in 2023–2024 when SDPI revived it in April 2023, followed by Sunni Yuvajana Sangham leader Mustafa Mundupara’s call in June 2024 for a “Separate Malabar State” from Kasaragod to Palakkad.

In 2024, independent MLA PV Anvar, through his newly floated Democratic Movement of Kerala (DMK), proposed creating a 15th district by combining parts of northern Malappuram and southern Kozhikode, citing administrative inefficiency due to overpopulation.

The IUML’s internal stance on bifurcation has been cautious. Senior leader PK Kunhalikutty, speaking at a literature festival earlier this year, said the party would support the move only if it genuinely aids development and avoids communal polarisation.

Moideen’s latest remarks, however, have exposed renewed divisions within the League on this sensitive issue.

Despite recurring campaigns and local resolutions, successive governments — both UDF and LDF — have rejected the proposal, terming it “unscientific and politically motivated.”

With no official studies or decisions in progress, the bifurcation of Malappuram remains a contentious political flashpoint rather than an imminent administrative reform.

As debates intensify once again, the idea of a “Tirur district” or “Edappal district” continues to oscillate between regional aspiration and political expediency, reflecting the larger complexities of identity and development in Malappuram, where a vast and diverse voter base makes every election a test of strategy and sentiment.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).