The mukthiyar system, once seen as indispensable in the unique context of Lakshadweep, is now standing at the brink of extinction. In the first week of August, the Lakshadweep Bar Association urged the Kerala High Court to abolish it altogether.

Published Aug 26, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Sep 12, 2025 | 11:33 AM

Mukthiyar system took root historically due to the islands' geographical isolation and administrative challenges.

Synopsis: Mukthiyars are individuals familiar with Lakshadweep’s customary laws who represent clients in legal matters without being qualified advocates, authorised through a mukhtyarnama (a document signed by the litigant granting authorisation for representation) executed by litigants.

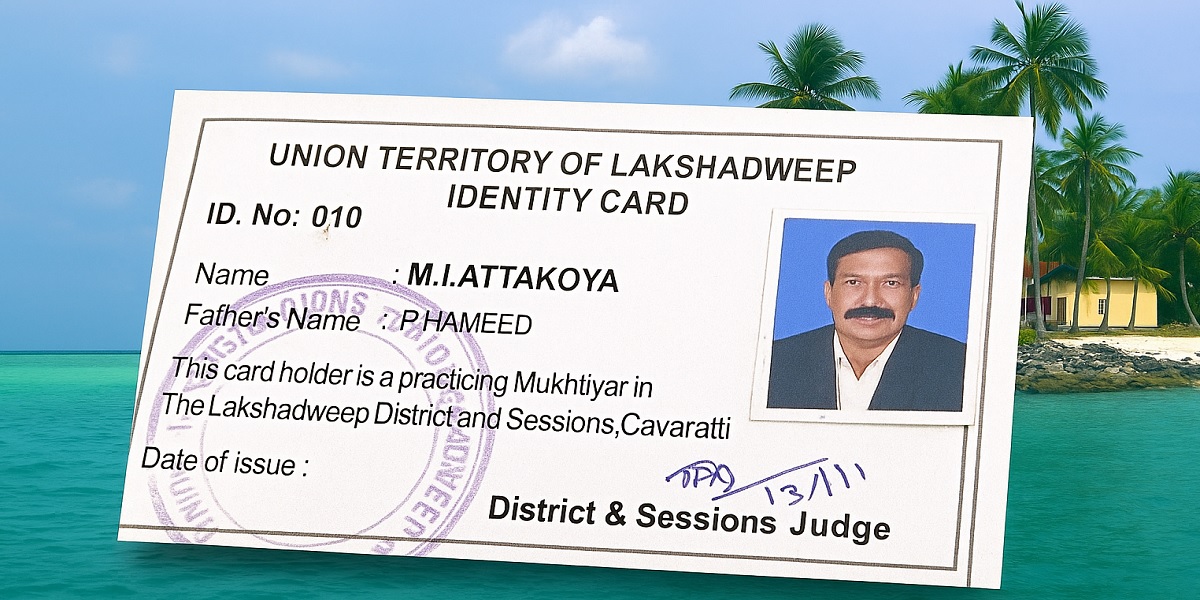

Name: M.I. Attakoya

ID No: 010. This card holder is a practicing mukthiyar in the Lakshadweep District and Sessions Court, Kavaratti.

For over four decades, Attakoya from Kavaratti has carried an identity that is far more than just a professional title; he has been a Mukthiyar of Lakshadweep, one of the last representatives of a tradition deeply woven into the island’s legal and cultural fabric.

For him, the role was never merely about appearing in court or representing people before the law. It was about trust, about being the bridge between his community and justice. But today, that pride is heavy with sorrow.

The mukthiyar system, once seen as indispensable in the unique context of Lakshadweep, is now standing at the brink of extinction. In the first week of August, the Lakshadweep Bar Association urged the Kerala High Court to abolish it altogether.

The mukthiyars of Lakshadweep, who once stood tall in the community, now watch as the system that defined them edges closer to its end, and with it, the closing of a chapter that may never be written again.

Mukthiyars are individuals familiar with Lakshadweep’s customary laws who represent clients in legal matters without being qualified advocates, authorised through a mukhtyarnama (a document signed by the litigant granting authorisation for representation) executed by litigants.

Mukthiyars of Lakshadweep

The system took root historically due to the islands’ geographical isolation and administrative challenges.

Speaking to South First, Attakoya, one of the senior mukthiyars, explained, ”The mukthiyar system was once prevalent across the country, including in Kerala, decades ago. In Lakshadweep, access to education was very limited, so law graduates were not available, and the system continued here.

Even though we didn’t have formal law degrees, we developed a deep understanding of Lakshadweep’s unique laws—like those relating to property possession. For instance, the islands still follow matrilineal inheritance, similar to what the Nair community in Kerala practised, while patriarchal inheritance also exists today.

Most of our cases involves civil disputes, though I have also appeared in criminal cases. The real issue now is that practicing advocates in Lakshadweep feel distressed, because many people still prefer approaching us. They find mukthiyars more approachable and trustworthy.”

Attakoya further explained, ”The interesting part is that Chief Justice Nitin M Jamdar and several legal experts from Kerala once visited us. They were very supportive, and at one point, there were even discussions about promoting us as advocates.

Also, The Mukthiyar Association has also been active in Lakshadweep.

At a time when there were no advocates in the archipelago, mukthiyars played a crucial role in protecting the laws of our land. “We never bargained for fees with clients. Our charges were minimal compared to those of advocates,” he said.

Even today, people from Lakshadweep take mukthiyars along to brief advocates in different parts of India for their cases.

We have been part of Lakshadweep’s history, yet now our very existence is in question. Only a handful of mukthiyars remain, fewer than 15, and the system is bound to fade with time. But why this sudden hurry to abolish the practice?

Attakoya’s son is now an advocate. “The younger generation is not following our path. they earn law degrees and pursue their careers.” he told South First.

When South First contacted Advocate Fathima Sulfath from Lakshadweep, who practices at the Kerala High Court, she explained, ”The case on the abolition of the mukthiyar system is still pending in the Chief Court because mukthiyars were impleaded. Under the Advocates Act, a person without a law degree can appear for a client in court in certain situations. This is different from representing oneself. Section 32 allows a non-advocate to represent another party in a specific case, but with restrictions.”

She added that with the growth of legal infrastructure and the increasing presence of trained advocates, the relevance of the mukthiyar system is now under question.

The Lakshadweep Bar Association has pointed out the lack of regulation, oversight, and standardized qualifications for mukthiyars, which could affect the administration of justice, especially in criminal cases.

With qualified lawyers available locally, the Association considers the system largely redundant.

The Lakshadweep Mukthiyar Association has approached the Kerala High Court to be impleaded, seeking recognition of experienced mukthiyars under Section 24(3) of the Advocates Act, 1961, which permits state bar councils to enroll individuals with special qualifications.

Advocate Enoch David Simon Joel, serving as amicus curiae, highlighted that the mukthiyar system lacks clear eligibility criteria, selection norms, and accountability. Allowing non-lawyers to represent clients, especially in criminal cases, breaches Article 22(1) of the Constitution and Section 340 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023.

“Courts are practically bound to accept mukthiyars, but they remain outside the statutory framework. Most of them are former government employees who exploit their knowledge of land acquisition cases, approach clients, and charge hefty percentages of compensation running into lakhs. People, often unaware, end up exploited. While complaints can be filed against lawyers through legal councils, there is no such mechanism against mukthiyars. If they wish to practice, they should be required to enrol as advocates,” he said.

He advised gradually abolishing the system while raising public awareness about the statutory invalidity of mukthiyars under the Advocates Act, 1961, which does not currently extend to Lakshadweep.

Recognising the impact on existing mukthiyars, he suggested welfare measures under the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987, and proposed involving experienced mukthiyars in ADR processes like mediation, where formal legal representation is not required.

Amid the ongoing debate over the mukthiyar system in Lakshadweep, the Kerala High Court on Thursday, 21 August, ordered the formation of a Lakshadweep Judicial Administration and Infrastructure Committee to strengthen the Union Territory’s judicial system.

Joel told South First that the recent order makes no mention of the mukthiyar system.

The move comes in response to persistent challenges in judicial infrastructure and staffing, with residents across several islands facing difficulties in accessing courts. Although Lakshadweep has 10 inhabited islands, court services are currently available on only three—Kavaratti, Androth, and Amini—restricting legal access for people on the remaining islands.

The newly formed committee is tasked with providing better administrative and infrastructure support to the courts in the Union Territory.

Its members will include the Registrar General, Principal District Judge, District Collector, a nominee of the Administrator, Superintendent of Police, Registrar (Computerisation), and a representative of NIC, the court said.

The directive came during a suo motu case initiated to address these systemic issues, with the Special Bench headed by Chief Justice Nitin Jamdar and Justice Ziyad Rahman AA.

Lakshadweep is witnessing rapid changes, both culturally and legally. Yet, this small and vulnerable community asks for time, asks for choices—something denied to them in many of the recent issues emerging from the islands.

As Attakoya, one of the last mukthiyars, says, people must first understand why Lakshadweep is in this situation, and then find a way forward, together. “We are not behind because of our faults, but because our unique circumstances were ignored,” he explained.

“All we ask is, see us, hear us, and stand with us as these changes come. The heart of Lakshadweep is its people, and we deserve dignity, respect, and a future shaped by our own voice, even in matters of justice,” he added.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).