Published Jan 03, 2025 | 12:00 PM ⚊ Updated Jan 06, 2025 | 11:22 AM

Kerala tops wage charts but trails in gender pay equity. (South First)

This report is the first in a series analysing gender-based wage gaps in South Indian states. The Union Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation recently released a report examining the roles of men and women across various sectors. The findings highlight a significant disparity in earnings, with women in India earning considerably less than their male counterparts.

“They say women’s work is not as productive, but we do twice the amount. Men leave after a few hours but we stay back to finish everything,” Geetha, a 46-year-old paddy worker from Palakkad in Kerala, told South First.

She said she earns ₹580 per day compared to ₹800 earned by her male counterparts. Her tasks include transplanting seedlings and weeding — work considered “unskilled” and, therefore, paid less.

Kerala boasts some of the highest daily wages for workers across the country but a deep-rooted gender pay gap continues to cast a shadow over its labour market, highlighting persistent inequality in one of the nation’s most forward-thinking regions. It presents a glaring paradox regarding wages.

A recent Union Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation report, Women and Men in India, 2023, underscores this disparity.

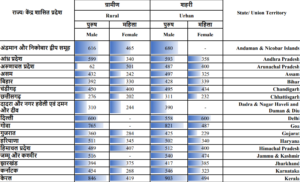

While male casual labourers in rural Kerala earn an impressive ₹846 per day — nearly double the national average — their female counterparts earn a mere ₹419, less than half of what men make for similar work.

Average Wage Earning (in Rs.) received per day by Casual Labourers in works other than Public.

Works (Apr-Jun, 2023) (Source: Women and Men in India, 2023 Report)

In urban areas, the situation is even worse, with men earning ₹903 daily and women ₹494, translating to a pay gap of 45.29 percent.

Kerala has consistently ranked at the top for daily wages in both rural and urban areas.

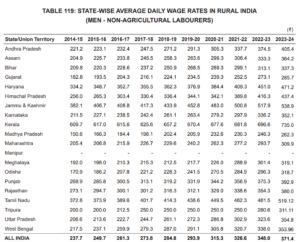

The Reserve Bank of India’s Handbook of Statistics on Indian States highlights that the average daily wage for a rural worker in Kerala exceeds ₹700, which is twice the national average.

State-wise average daily wage rates in rural India (men — non-agricultural labourers)

Source: RBI’s Handbook of Statistics on Indian States

Skilled workers, including carpenters and masons, have seen steady wage growth over the years.

For instance, the daily wage rate for carpenters increased from ₹973.03 in 2021–22 to ₹1,015.73 in 2022–23, while masons saw their wages rise from ₹978.45 to ₹1,018.46 during the same period.

These figures point to Kerala’s relatively high labour costs, driven by a history of strong labour movements and minimum wage regulations.

Despite these wage highs, women in Kerala remain at the lower end of the spectrum.

The gender pay gap in casual labour — particularly in agriculture and construction — reveals a troubling picture.

Women casual workers, who are predominantly engaged in unskilled work, earn significantly less than men, even when performing similar tasks.

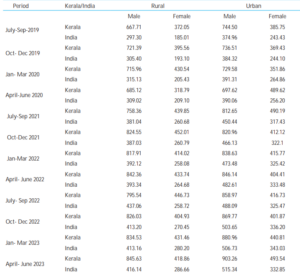

In the agricultural sector, for instance, male unskilled workers earned an average of ₹781.75 per day in 2021–22, compared to ₹577.73 for female workers.

Gender Difference in Average Wage/Salary/Earnings per day from casual labour work other than public work

(Source: Periodic Labour Force Survey 2022-23)

While women’s wages grew at a higher rate (6.03%) than men’s (1.34%) the following year, the gap remained substantial at ₹179.62 in 2022–23.

This disparity is rooted in systemic discrimination and occupational segregation, where women are largely confined to low-paying, manual tasks deemed “unskilled.”

Despite a small wage increase in recent years, the gap remains significant.

The construction sector paints a similar picture. In the third quarter of 2023–24, the average daily wage for male unskilled workers stood at ₹853.57, while women earned ₹778.57.

Ranjitha (name changed as per request), a 34-year-old construction worker from Odisha who has been working at a site in Thiruvananthapuram city for the last year, told South First that while her male colleagues earn ₹850 per day, she is paid only ₹600 for the same tasks, such as carrying bricks and mixing cement.

“We work the same hours, but our pay is always less. Most of us don’t know the wage regulations here, so we don’t ask for more,” she said.

Her contractor justified the disparity by claiming that men handle heavier tasks, but Ranjitha refuted it.

“Even when we do the same work, we are paid less. We don’t argue because we fear losing our jobs,” added Ranjitha.

At the same time, according to the data compiled by the Kerala Directorate of Economics and Statistics, in the housing sector, unskilled workers’ labour wage rates — for both men and women —in Thiruvananthapuram is ₹900. The state average is ₹857.14 for men and ₹778.57 for women.

Considering Ranjitha’s account, the construction workers at her site — both men and women — earned wages below the state average.

Her friend Anita Devi, who works in the construction sector in Kozhikode also shared a similar experience. She and other women earn ₹550 per day, while male workers from the same group earn ₹800.

“We were told this is the standard pay for women workers. None of us knew we could demand more,” she told South First.

At the same time, labour wage rates as compiled by the Kerala Directorate of Economics and Statistics mentioned that in Kozhikode, a male unskilled worker will get ₹900 and an unskilled women labourer will get ₹800.

Labour Department officials point out that most women migrant workers are unaware of their rights and the state’s minimum wage laws, making them vulnerable to exploitation.

The economic disparity is not limited to wage rates.

Kerala’s labour market reflects broader systemic issues, such as the undervaluation of women’s work, occupational segregation, and cultural perceptions of gender roles.

Women in agriculture, for instance, are often assigned manual tasks considered unskilled and therefore less productive.

This classification justifies lower pay, even though women often work harder and for longer hours than their male counterparts.

In the cashew industry, strict gender-based divisions of labour keep women in lower-paid roles, perpetuating economic dependence and limiting their social status and decision-making power.

While the Equal Remuneration Act of 1976 mandates equal pay for equal work, its implementation faces challenges in unorganised sectors where defining “similar work” is often subjective.

Differences in task allocation and skill levels are frequently used to justify wage gaps, exacerbating inequality.

The Economic Review of Kerala 2023 acknowledges wage disparity as a significant area of concern.

It notes that gender inequality in earnings is more pronounced in casual labour than in salaried jobs or self-employment.

Even though women in Kerala earn more than their counterparts in other states, their wages remain substantially lower than their male counterparts.

This disparity is evident across sectors. An analysis of hourly wages in nine occupational categories revealed that men earned more than women in almost all fields, from professionals to service workers.

The review emphasises that reducing the wage gap is crucial for the economic empowerment of women.

It calls for policies that address unpaid household and caregiving responsibilities, which disproportionately fall on women. Redistributing these responsibilities within households and implementing supportive state policies are essential steps toward gender parity.

Kerala has made strides in raising minimum wages across sectors, which has benefited women to some extent.

The state’s agricultural sector provides an illustrative example, where the wage gap between male and female unskilled workers decreased from ₹204.02 in 2021–22 to ₹179.62 in 2022–23.

However, these incremental gains are insufficient to address the structural issues underlying wage inequality. The concentration of women in low-paying jobs and their limited bargaining power remain significant barriers.

To ensure true economic empowerment, Kerala must adopt a multi-pronged approach, say Labour Department officials.

This includes implementing robust policies to enforce equal pay, addressing occupational segregation, and providing skill development programmes to help women transition into higher-paying roles.

The state must also promote shared household responsibilities and recognise the economic value of unpaid caregiving work.

While Kerala’s high wages set a benchmark for the rest of the country, its persistent gender pay gap is a stark reminder that economic growth does not automatically translate into equity.

Bridging this gap is not only a matter of justice but also a critical step toward achieving inclusive development.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).