Published Aug 13, 2024 | 6:00 PM ⚊ Updated Aug 13, 2024 | 6:00 PM

Kerala has made enviable achievements in healthcare, which the state does not hesitate to flaunt at any given opportunity.

It was the state’s confidence in its healthcare system — on par with any developed European nation — that made it invite Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath to learn from its hospitals in October 2017.

Beneath all the hullabaloo over Kerala’s achievements the state, apparently, is found lacking in effectively preventing the outbreak of diseases.

As many as 144 people have died till July this year due to infectious diseases, denting the state’s pride built over the past 200 years. Deaths due to chikungunya and dengue have ceased to be news, and are often relegated to single columns — if not ignored — on inside pages of newspapers.

Of late, Kerala has been witnessing sporadic outbreaks of infectious diseases. It detected Nipah virus encephalitis — the second state in the country after West Bengal (2001 and 2007) to do so — on 19 May 2018. As many as 23 cases were then identified.

The virus reared its deadly head again in September 2021, and then in August and September 2023. A case was reported from Ernakulam in 2019 also. The latest was confirmed on 10 June 2024, and the patient, a 14-year-old boy, died under medical care the next day.

Nipah was not the last fatal disease reported this year. On 7 August, Health Minister Veena George told reporters that five deaths due to amoebic meningoencephalitis, a rare and fatal brain infection, had been reported in the first eight months.

Kerala Health Minister Veena George. (Facebook)

She said that 15 cases of the infection were reported. Among them, seven of the single-cell brain-eating Naegleria fowleri amoebic infections were in Thiruvananthapuram, the state capital.

On 9 July, a cholera outbreak killed a 26-year-old man, a resident of a special school at Neyyattinkara, around 15 kilometres south of Thiruvananthapuram city.

The cholera death, incidentally, was the first in seven years in Kerala. Inadequate sanitation and contaminated water were the reasons cited for the outbreak.

The first 11 days of July saw 1,357 reported cases of vector-borne dengue and 124 cases of leptospirosis, a zoonotic disease. The death toll was seven.

Speaking to South First, Dr B Iqbal, public health activist and chairperson of Kerala’s Covid Expert Committee, infectious diseases have become “endemic to the region, with fluctuating intensity”.

“Kerala is seeing a significant increase in the spread of infectious diseases in recent years,” he said over the phone.

“Diseases such as dengue, chikungunya, H1N1, gastroenteritis, leptospirosis, West Nile virus, Japanese encephalitis, scrub typhus, leishmaniasis, and Kyasanur Forest Disease have become endemic in the region, with fluctuating intensity,” he elaborated.

Dr Iqbal further said the diseases, including amoebic meningoencephalitis has claimed 144 lives till July.

The Kerala State Planning Board highlighted several key health issues and challenges in its Economic Review, 2017.

Kerala has the highest suicide rate at 28.5 per 1,00,000 population.

Kerala has achieved impressive health indices such as high life expectancy, and low infant mortality, birth, and death rates.

However, the report raised concern over non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart disease, cancer, and geriatric issues.

It also noted that the state has been facing increasing incidences of communicable diseases such as chikungunya, dengue, leptospirosis, and swine flu.

Health experts called for robust surveillance and response systems to counter these challenges. They also underscored the need for targeted interventions and support systems to address new threats such as mental health issues, suicide, substance abuse, alcoholism, adolescent health problems, and rising road traffic accidents.

According to the National Crime Records Bureau’s 2022 report, among the geographically larger and more populous states, Kerala has the highest suicide rate at 28.5 per 1,00,000 population, followed by Chhattisgarh at 28.2, and Telangana at 26.2.

The experts also pointed out that health disparities were notable among marginalised communities such as tribespeople and fishermen. They demanded special attention to address the inequities.

The Economic Review underscored the need for concerted action and collaboration to address multifaceted health issues and ensure sustained improvements in public health in Kerala.

Kerala’s healthcare system has seen significant advancements, largely due to the efforts of the Aardram Mission. The initiative has established specialised clinics to address non-communicable diseases, mental health issues, and respiratory conditions.

The project has ensured the availability of essential medicines and upgraded treatment infrastructure at primary health centres. Most taluk, district, and medical college hospitals offer services comparable to those in private healthcare institutions, both in terms of modern technology and human resources.

As a result, the utilisation of government hospital services has seen a significant increase, with approximately 60-70 percent of the population now accessing care through these facilities, Minister George said.

A government doctor working for the National Health Mission said the state needed public health interventions to tackle the present crises.

“The expertise of public health professionals available at various institutions has not been fully utilised,” he said requesting anonymity since he was not authorised to speak to the media.

He further stated that to address Kerala’s health challenges more effectively, the state should harness the professionals’ capabilities for detailed studies and public health interventions.

“A programme should be developed to leverage the expertise of these professionals in collaboration with government and private medical colleges, public health institutions, and local self-government bodies,” he opined.

“This programme should focus on studying regional health issues, suggesting solutions, and assisting in the preparation of health projects and other initiatives” he added.

The Government of Kerala established the State PEID (Programme for the Elimination of Infectious Diseases) cell in 1982 at the Medical College Hospital in Thiruvananthapuram. The intention was to enhance the state’s surveillance system for infectious diseases.

To further bolster the initiative, Regional PEID (RPEID) cells were set up in all Government Medical Colleges in 1989.

The Regional PEID cells, along with the State PEID cell, have been providing valuable surveillance data on communicable diseases to the health services.

In addition to data dissemination, the PEID cells were involved in various activities, such as advancing knowledge on disease control, conducting research, training health personnel, and assisting state and district authorities in managing epidemics.

The Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme (IDSP) functioning in every state, including Kerala, has created a decentralised, state-based system to enhance disease surveillance, ensure timely public health responses, and improve information sharing for effective disease control and evaluation.

Dr Thomas Jibin, the Coordinator of the Ernakulam Epidemic Cell, pointed at another vexing issue that has been countering healthcare initiatives.

“Awareness programmes and medical camps are being conducted in every nook and corner of the district. Guidelines have been provided to prevent mosquito bites and to clean wells. Without a proper waste management system, nothing will be effective,” he told South First.

“In the past, chlorination programmes in both rural and urban areas were undertaken by local bodies. Now it is high time that we evaluated whether these small steps are being effectively implemented,” he continued.

“We share daily data with the health department regarding the number of cases of infectious diseases. However, more research and studies are needed to reduce the increasing number of tropical diseases in Kerala,” Dr Jibin said.

Despite drawbacks, Kerala still pulls off surprises, thanks to its time-tested healthcare system.

In a remarkable achievement, a 14-year-old boy recovered from amoebic meningoencephalitis infection, a condition with an almost 99 percent mortality rate.

Terming his recovery exceptionally rare, Minister George said on 23 July that only 11 people in the world had won the battle against the deadly amoeba. It was India’s first case also.

The country’s second case of recovery, too, came from Kerala. On 7 August, a four-year-old boy also overcame this deadly illness.

Dr Iqbal said Kerala has long been recognised for its impressive healthcare achievements, particularly in terms of indicators like infant mortality rate and life expectancy.

“This reputation reflects the state’s strong healthcare infrastructure and commitment to providing high-quality medical care,” he said.

“However, despite these successes, Kerala faces a significant challenge with communicable diseases that have been eradicated or controlled in other developing nations with robust healthcare systems, such as Cuba, Nicaragua, and Sri Lanka” Dr Iqbal said.

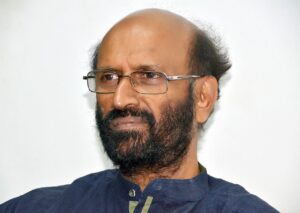

Dr B Iqbal. (Syed Shiyaz Mirza/Wikimedia Commons)

He also opined that while Kerala excelled in treatment, it should intensify its focus on disease prevention.

“The persistence of certain communicable diseases in Kerala indicates a need for a more proactive approach to public health. If these issues are not addressed, there is a risk that Kerala could fall behind in global healthcare rankings, despite its strengths in treatment and care,” he warned.

“To address these concerns, Kerala’s Health University and other research institutions must lead efforts in studying these specific health issues,” he urged.

“Enhanced research can contribute to developing effective prevention strategies, which are vital for controlling disease outbreaks. By integrating advanced treatment capabilities with robust preventive measures, Kerala can ensure that it not only maintains its healthcare excellence but also improves its overall health outcomes,” Dr Iqbal added.

Kerala’s public health system has a rich history, dating back to over 200 years.

Queen Gouri Lakshmi Bai. (Wikimedia Commons)

In the early 19th century, Queen Ayilyam Thirunal Gauri Lakshmi Bai of the now erst-while kingdom of Travancore played a pioneering role by establishing a vaccination department in 1831.

Her commitment to vaccination, including having her family vaccinated against smallpox, helped dispel fears about new medicines and set a precedent for public health.

Her successor, Rani Gauri Parvathi Bai, furthered the mission by founding a charity dispensary to provide medical care to ordinary citizens. By the late 19th century, Travancore boasted of 31 hospitals, reflecting the region’s growing investment in healthcare.

The 20th century saw continued advancements in Kerala’s healthcare infrastructure. In 1935, the state faced significant health challenges due to malaria and filariasis, prompting the establishment of a well-equipped Public Health Laboratory in 1937.

This facility was instrumental in diagnostic testing, vaccine production, and anti-rabies treatment. The General Hospital, originally known as the Civil Hospital and established in 1865 by King Ayilyam Thirunal, represented a major milestone in the state’s healthcare development.

By 1958, Kerala had expanded its healthcare system to include 53 government hospitals and 198 dispensaries, offering over 9,300 beds.

These historical milestones underscore that the “Kerala Model” of public health is not a recent phenomenon but rather the culmination of over two centuries of progressive healthcare practices.

The state’s long-standing commitment to healthcare continues to shape its public health policies today.

(Edited by Majnu Babu)

(South First is now on WhatsApp and Telegram)