Crudely-made bombs are a sordid but inalienable part of politics in Kannur, with political parties using them indiscriminately.

Police exhibiting seized crude country bombs at Panur in Kannur on February 12, 2022. (SK Mohan/South First)

Medical practitioner K Asna, 26, has only flickering memories of that fateful evening 22 years ago when she lost a limb in a bomb attack.

She would never run or skip again.

“It was September 7, 2000,” recalls Asna. “I was playing with my brother Appu in the courtyard at my uncle’s house when some friends of his ran into our compound looking for a place to hide.”

Chasing them was an angry mob, which followed them inside, shouting all the while. “I remember my mother frantically calling out to us as she ran out of the house. Suddenly, there was a loud blast, and immediately, an excruciating pain shot through my body.”

The “blast” four-year-old Asna heard was the explosion of a crude bomb hurled by the intruders chasing her uncle’s friends. The pain was from her right leg being ripped off.

Her baby brother Appu, then aged three, had flesh blown off his feet. Shards of glass got lodged into their mother’s stomach.

The three were yet more victims of Kannur’s infamous “bomb culture”.

Over the past two decades, crudely-made bombs have become a sordid but inalienable part of politics in Kannur district, with political parties using them indiscriminately to browbeat rivals.

Not surprisingly, among Kerala’s 14 districts, Kannur has the dubious distinction of having the highest number of cases registered under the Explosive Substances Act of 1908.

The district police registered 46 cases under the Act in 2021. This year, the number has already touched 20, though according to locals, the actual incidence of violations may be higher.

All political parties are guilty of using the “bomb tactic”, say those in the know, with the ruling CPI(M), which boasts of having the strongest district unit nationally in Kannur, leading the pack. It is unwilling to cede ground and the crude bombs bolster its muscle power.

The Congress party — its principal rival — and the Islamic outfit SDPI are also said to have their own “experts” in making crude explosives. Today, even the BJP-RSS combine is believed to use bombs against its rivals.

It is an ingoing tit-for-tat battle. For instance, CPI(M) leader P Jayarajan lost his hand in August 1999 after BJP workers barged into his house and hurled bombs at him. The following year, CPI(M) goons entered a primary school and killed a teacher, KT Jayakrishnan, a BJP man.

Even the blast that maimed Asna was the fallout of rivalry between BJP-RSS workers and Congress sympathisers at Cheruvanchery village in Kannur, where her uncle, a Congress loyalist, lives. The trigger was a local by-election.

So how does the scare tactics with the bombs work? Wouldn’t the use of guns suffice just as well?

For the record, political goons also use guns and blades, but the crude bombs have extra “benefits”. First, there is the fear of a gruesome death or living with crippling injuries, as these bombs contain glass pieces and iron nails that pierce the target’s body.

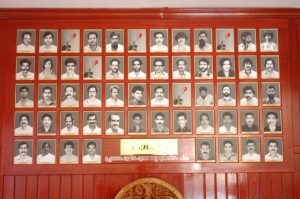

Pictures of BJP activists killed in bomb attacks and attacks using lethal weapons displayed at its district office in Kannur. (SK Mohan/South First)

“The aim is to maximise the pain,” KA Antony, a Kannur-based political observer who has been tracking political violence in the district since 1970, told South First.

In the beginning, these were just improved versions of powerful firecrackers. Over the years, the power of the bombs has been enhanced and now, steel containers are used so that the impact is more lethal.

This brings us to the second use of the bomb: Creating terror and deterrence, Gandhian activist Aneesh Thillankeri told South First.

The loud blast immediately instils fear among people in the area, dents their confidence, and stops them from helping the target or resisting the attackers,

Then there is the third aspect, Thillankeri says: The smoke billowing from the explosion obscures vision, preventing witnesses from identifying those responsible.

“The accused can defend themselves in courts questioning the ability of witnesses to identify anyone in a smoky atmosphere,” he says.

Where did it all begin? According to Antony, Kannur’s bomb culture in is not a new thing, and can be traced to the 1960s.

The bombs then were used by the region’s impoverished beedi workers when they decided to use violence to resist operations against them by Mangalore-based beedi companies.

Their tactics were then copied by political parties.

According to the writer Prabhakaran Pazhassi, crude bombs were first used in political warfare in Kannur on April 29, 1969, when alleged CPI(M) workers exploded a few to terrorise bystanders before axing to death one Vadikkal Ramakrishnan, a rival from the Sangh Parivar.

The list of CPI(M) workers killed either by bombs or lethal weapons by political opponents adorn the walls of the party’s district office in Kannur. (SK Mohan/South First)

The second instance was in 1976 when CPI(M) worker Kulangarath Raghavan was hacked to death by alleged RSS cadres. This time, too, bombs were first exploded to fan terror.

In 1979, a CPI(M) worker named Thadathil Balan was killed with lethal weapons after the attackers hurled bombs to scare away people in the immediate vicinity.

These incidents were isolated and far between, but by the beginning of the 1980s, the practice of using bombs had taken deeper socio-political roots in Kannur. Today, political parties openly defend it.

Argues the CPI(M)’s district secretary MV Jayarajan: “This is self-defence and self-defence is not violence.”

In his view, it is the BJP-RSS combine, the Congress, and different Islamic outfits in the district that are promoting the bomb culture. The opposition, on its part, levels similar charges against the ruling party.

The role of political patronage

The protective arm of local politicians is clearly visible in the villages where bomb-making is rampant. Spread across areas such as Panur, Koothuparamba, Iritty, Chockli, Ponnyam and Kizhoor, these Kannur villages are strongholds of either the CPI(M) or the RSS.

The hideouts where the bombs are manufactured are tucked away in desolate river islands, vacant plots, forest areas and hill slopes.

So brazen are the bomb-makers that, the police say, they frequently purchase their ingredients — ammonium nitrate, potassium chloride, aluminium powder, etc. — from local quarry operators, who import the materials from China to blast rocky terrains.

And it is this “open knowledge” that irks the BJP’s Kannur district president N Haridasan. In his view, what muddies the situation is the “lack of proper investigation” into the origins of the bombs, and subsequent action.

“Once the police trace down the sources of the explosives, they can take preventive measures,” he told South First. “But our experience is that they are tacitly helping these crimes.”

Haridasan also talks of “political affiliations”, implying that the ruling CPI(M)’s protective arm over the perpetrators is preventing a police crackdown.

On his part, the CPI(M)’s Jayarajan gives the cops a clean chit. “The police are doing their duty,” he says. “Many RSS-BJP activists have been rounded up for making bombs.”

Incidentally, a former district police chief, S Sreejith, once needed 14 surgeries to recover from a country bomb attack.

What is more worrisome is that of late, the bomb politics of Kannur has begun taking an ugly turn with gangs targeting social functions attended by political rivals.

According to sources in the police, goons with affiliations to mainstream parties drive into venues in dramatic fashion, brandish machetes to create terror among guests, and hurl bombs at their targets on spotting them.

Even personal rivalries are given a political colour, with crude bombs turning into tools of vengeance.

In February, a CPI(M) worker was arrested for hurling a crude bomb at a friend’s marriage party, killing one person and injuring four. Though crude country bombs are integral to Kannur politics, this was the first time that these were used at a wedding.

The incident at Thottada, on the outskirts of Kannur town, ironically killed one of the attackers, also belonging to the CPI(M). Apparently, the smokescreen they created blinded the gang-member hurling the bomb, resulting in his friend, aged only 24, being killed by mistake.

Not all deaths or bomb injuries are caused by planned attacks by political rivals or are poll-related like the Cheruvanchery incident involving Asna’s injury, says political observer Antony.

Crude bombs have been known to explode even during manufacturing, especially if the bomb-maker lacks enough experience and skill, or has been distracted.

For instance, three people were severely injured at Ponnyam village in September last year, when the bomb they were making exploded, with one losing both his arms.

“Whenever such an incident occurs, or somebody spots hidden bombs, political parties start blaming their rivals,” says Antony.

What is truly ghastly is the way these explosives claim lives when unsuspecting victims — whether humans or animals — stumble across the bombs stowed away in garbage dumps.

Family grieves over CPI(M) activist Anish, who was killed in December 2021 in a crude bomb attack. (SK Mohan/South First)

Earlier this year, the head of a street dog was blown off after the stray had disturbed a small steel container in a rubbish vat; the container had a live crude bomb hidden in it.

In 2015, Sajeevan of Panur, who was never associated with any political party, lost both his arms when he triggered off a hidden bomb while picking dry coconuts at a farm.

On July 7 this year, migrant ragpickers Fazal Haq and his son Shaheedul found a steel lunch box that exploded when they tried to open it, killing them both.

The state government has sent the bodies to the victims’ native place in Assam, while the CPI(M) and the opposition have traded charges in the Assembly over the incident. That was the end of the matter.

Not many people can survive an exploding steel container; Poornachandran, a clerk at a Kerala government-run music college, is one who has.

Poornachandran was a nine-year-old ragpicker from Tamil Nadu when he found a steel container while rummaging through garbage at Panur in Kannur. That was 24 years ago.

“I was excited when I found the little steel box, thinking I would be able to sell it and buy some food for my mother,” he recalls. “But when I tried to open it, it exploded.”

Poornachandran is not the name his mother had given him, which was “Amaavasi”, literally meaning “dark night”.

But after hearing his story — and learning of his inspiring will to survive — the late Marxist thinker P Govinda Pillai rechristened him Poornachandran, meaning “full moon”.

Today, Poornachandran is grateful to be alive. “I was lucky as I lost only my right hand and my right eye,” he says. But he also prefers anonymity and seeks to downplay the incident.

When his tragedy created headlines, the Saigramam orphanage in Thiruvananthapuram adopted him, and he began attending school.

He was bright student, and when he displayed a talent for music, the Saigramam management sent him for a BA Music course at Sri Swathi Thirunal College of Music at Thycaud. He also had the support of the poet Sugathakumary, apart from Govinda Pillai.

Thanks to the patronage he received after the tragedy, Poornachandran went on to earn a degree in music. Later, the then chief minister Oommen Chandy helped him get his current job on compassionate grounds.

Poornachandran is fighting not to sink under the weight of his disability. And there are others. As noted Malayalam writer Ambikasuthan Mangad says, “There are many living martyrs of Kannur’s political bombs.”

Mangad has labelled survivors thus because, in his words, “living with deformities and glass and steel particles pierced into the body is immensely painful”.

One such living martyr is, of course, Asna.

Asna’s family celebrates her appointment as doctor at the primary health centre in her village Cheruvanchery in March 2021. (SK Mohan/South First)

Refusing to let the violent incident of her childhood ruin her life, Asna completed her schooling and college, and then earned an MBBS degree. Today, she is a Medical Oficer at the Primary Health Centre at Cheruvanchery, Kannur.

Recalling what inspired her to choose her life’s calling, Asna says she was motivated by one Dr Sundaram, her attending physician at a Kochi hospital where she was undergoing treatment.

“Dr Sundaram had lost one of his legs in a car accident when young, but decided to take life head on with an artificial leg fitted,” she says. “That was the turning point. I too decided to become a doctor and live my life using an artificial limb,” Asna told South First.

And so, after spending 86 days in hospital, Asna returned home with a prosthetic leg; since then, she has had to change the artificial limb 17 times.

“In the beginning, as I grew older rapidly, I needed new prosthesis every three or four months. Later, this got reduced to a yearly occurrence. My present leg was fixed three months ago at Rs 1 lakh,” she says.

The story of Kannur’s politics is a never-ending litany of horror deaths and life-sapping injuries. No one is spared — not even babies like Appu or his little older sister, or harmless elderly women who just happened to be around when the bombs were hurled.

This must stop, say observers. “Families are falling into debt and extreme misery after the death of an earning member,” rues Antony. “I would say 99 percent of bomb victims are of humble backgrounds.”

A case in point is the fate of a clerk at a rural school at Chokli village, who was critically injured in 1990 when a bomb that a teacher had kept hidden in his bag exploded accidentally.

The teacher had Left leanings and later said he carried the bomb with him for self-defence.

The list of innocent victims is bound to grow, says Antony, because those who manufacture and explode the bombs are not known for their skill sets.

“There will be many occasions when the bombs fall on wrong targets,” he says. “It is high time that political parties in Kannur rethink their priorities.”

Agrees Asna. “I don’t have enmity even with those who attacked me, and treat people without looking into their political affiliations,” she says.

“But perpetrators of hate politics must be isolated.”

Apr 19, 2024

Apr 19, 2024

Apr 19, 2024

Apr 19, 2024

Apr 19, 2024