Published Oct 24, 2025 | 8:00 AM ⚊ Updated Oct 24, 2025 | 8:00 AM

Critics have long described kafala as a “modern form of slavery.”

Synopsis: Saudi Arabia has officially ended its decades-old kafala system, which tied lakhs of migrant workers, including 26 lakh Indian expatriates, to their employers and exposed them to exploitation such as unpaid wages, forced labour, and restricted mobility. The kingdom has replaced it with a contractual employment model that promises job mobility, digital wage transfers, and legal protections in an effort to improve its global image. Whether the reforms will translate into meaningful gains on the ground for Indians in the system, however, remains to be seen.

In June 2025, Saudi Arabia officially abolished its decades-old and much-criticised kafala (sponsorship) system.

For decades, it tied the fates of lakhs of migrant workers to their employers and made it almost impossible for workers to change jobs or leave the country without their employer’s consent.

Critics have long described it as a “modern form of slavery,” pointing to abuses such as passport confiscation, unpaid wages, forced labour, poor living conditions, and even sexual abuse.

Now, Riyadh is introducing a contractual employment model aimed at giving workers more mobility and rights.

For the 26 lakh Indian expatriates in the country, the question is whether this long-awaited reform will finally bring dignity, freedom, and fair working conditions.

The initiative may now enable job mobility without the need for prior employer approval, grants workers the right to travel, exit, or return by simply notifying employers electronically – a NORKA official.

The kafala system is a legal framework governing the relationship between migrant workers and their local sponsors—known as kafeel—across Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, including Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, as well as in Jordan and Lebanon.

Originating in the early 20th century to regulate the employment of foreign labourers in the Gulf’s pearl industry, the system expanded during the 1950s oil boom to meet the growing demand for cheap, temporary labour.

Its main purpose was to allow Gulf states, with relatively small native populations, to import and expel labour quickly in response to economic fluctuations.

Under kafala, a migrant’s legal status is tied to their employer, who must grant explicit permission for the worker to enter the country, change jobs, or leave.

This gives employers significant control over workers’ mobility and legal rights, creating a deep power imbalance. Although countries like Bahrain and Qatar claim to have abolished the system, rights groups say reforms are poorly enforced.

The system also enforces what migration scholars call “differential exclusion,” where migrants contribute economically but remain excluded from welfare, citizenship, and political participation.

As a result, the kafala model continues to face global criticism for institutionalising exploitation and denying millions of migrant workers basic human and labour rights.

Saudi Arabia’s decision to abolish the system comes after years of global criticism and at a crucial moment: ahead of the 2034 FIFA World Cup, which the country will host.

The move, central to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s Vision 2030 blueprint, is seen as part of the Kingdom’s effort to modernise its labour market, uphold internationally accepted human rights norms, and improve its global image ahead of the prestigious sporting event.

Although Saudi Arabia had removed the term “kafala” from labour law as early as 2000, meaningful reform only gained traction after Vision 2030 was launched in 2016, which identified a flexible and transparent labour ecosystem as vital to economic diversification.

Following years of consultations and mounting international scrutiny, the government introduced the Labor Reform Initiative (LRI) in 2020, effective March 2021, granting limited job mobility and independent visa access to private-sector workers.

However, these were transitional measures.

The decisive step came in March 2025, when the Saudi Press Agency (SPA), the state news agency, announced the Kingdom’s intent to replace kafala entirely with a contractual model – emphasising justice, worker independence, and human dignity as national priorities.

Three months later, the reform was fully implemented, allowing all 1.3 crore migrant workers, including domestic staff, to change employers, travel, and manage residency without sponsor consent.

According to SPA, a comprehensive legal framework has been established in the Kingdom to protect the rights of expatriate workers and ensure justice and transparency.

For the nearly 26 lakh Indians—from Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and Gujarat—living and working in Saudi Arabia, the system’s impact was profound, affecting families across the country.

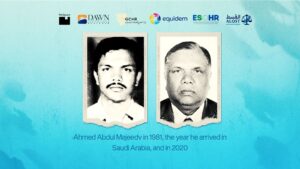

The case of Ahmed Abdul Majeed, highlighted by ALQST for Human Rights, an NGO in Saudi Arabia, in September, stands as a reminder of the enduring brutality of the kafala system and its devastating impact on Indian expatriates in Saudi Arabia.

When various organizations put together a joint appeal for justice for Indian victim of Saudi Arabia’s kafala system. Image courtesy: ALQST.

After devoting four decades of service to Al Tayyar Travel—later restructured as Seera Group under the state-controlled Public Investment Fund (PIF)—Abdul Majeed was abruptly terminated during the COVID-19 pandemic, stripped of his rights, and trapped in the kingdom without his passport.

Denied permission to return home to his ailing wife, he was coerced into working without pay and even forced to repay $100,000 in client debts from his own pocket.

His ordeal, which included wage theft, passport confiscation, and emotional torment, exposes the systemic cruelty and impunity enabled by kafala, says the NGO.

It alleged that despite Saudi Arabia’s claims of reform, the system continues to breed exploitation under state and corporate complicity.

Cases like that of the Karnataka nurse and the Gujarat domestic worker—both victims of abuse trapped by kafala restrictions in 2017—are further examples of the excesses of the kafala system.

But despite its flaws, kafala had its merits: it offered access to higher-paying jobs in construction, domestic work, and healthcare – opportunities unavailable at home.

Remittances from Saudi Arabia became a lifeline for millions, strengthening rural economies and helping families escape poverty.

With the system’s abolition, reforms such as job mobility without employer consent, digital wage transfers, and dispute redressal mechanisms promise a fairer and safer work environment.

Officials note that India’s bilateral labour agreements with Saudi Arabia now provide additional safeguards, including equal treatment, social security benefits, and repatriation support.

An official from Kerala’s Department of Non-Resident Keralites Affairs (NORKA) said the abolition significantly strengthens the rights and welfare of expatriate workers, including thousands of Malayalis.

The official added that the shift to a contractual relationship framework marks a decisive move towards a more transparent and equitable labour environment, in line with the Kingdom’s Vision 2030 and National Transformation Programme.

“The initiative may now enable job mobility without the need for prior employer approval, grants workers the right to travel, exit, or return by simply notifying employers electronically, and ensures a greater degree of independence and dignity in employment,” the official said.

The NORKA official also highlighted supporting measures like the “Wage Protection Programme,” which mandates timely wage disbursement through a monitored electronic system, promoting accountability and reducing disputes.

The official further noted that the Musaned platform’s domestic worker contract insurance service—covering over 500,000 workers—may strengthen protection by ensuring compensation for injuries, unpaid salaries, or employer-related contingencies.

(Edited by Dese Gowda)