Relying solely on basic chemical fertilizers could reduce crop yield to just 20–40% of current levels, which is insufficient to sustain the population.

Published Apr 01, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Apr 12, 2025 | 11:28 AM

According to the latest Economic Review 2024, the total paddy cultivation area in 2023-24 was 1.7895 lakh hectares, which is a 5.9% decline compared to 1.9017 lakh hectares in 2022-23.

Synopsis: Kerala is witnessing a dip in rice production even as chemophobia makes people frown at the use of chemical fertilisers. Organic farming, though sounds romantic, will not meet the requirements of Kerala, a state heavily dependent on others for food.

Kerala’s rice fields, often described as the state’s green veins, play a crucial role in shaping its landscape and agricultural identity. However, rice cultivation has been steadily declining, raising serious concerns about the future of paddy farming.

Once known as Kerala’s rice bowl, regions like Kuttanad in Alappuzha and Palakkad are witnessing a significant reduction in paddy cultivation.

The Economic Review 2024, presented in the state Assembly, highlighted an alarming drop in rice production, productivity, and the total area under cultivation.

Several factors have contributed to this decline. One major issue is the shifting perception of chemical fertilisers. While they are essential for ensuring high yields, public apprehension, fueled by social media narratives and unscientific claims, has led to a growing reluctance to use them.

Additionally, changing land-use patterns, labour shortage, and climate-related challenges have further exacerbated the crisis.

South First investigation found that the term ‘organic’ is widely commercialised and has even created chemophobia among people, ultimately putting farmers and small-scale businesses at risk.

The Economic Review 2024 reveals that the area under wetland rice cultivation in Kerala dropped by 5.9% in the 2023-24 financial year, falling from 1.90 lakh hectares in 2022-23 to 1.78 lakh hectares.

The Economic Review 2024 highlighted an alarming drop in rice production, productivity, and the total area under cultivation.

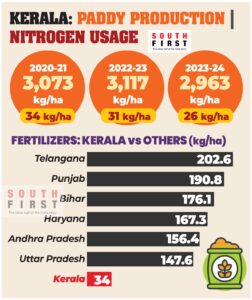

Correspondingly, production declined from 5.92 lakh tonnes to 5.3 lakh tonnes, marking a 10.5% decrease. Productivity also took a hit, sliding from 3,117 kg per hectare to 2,963 kg per hectare, a 4.9% decline.

Among the rice-producing districts, Palakkad recorded the most substantial drop in production at 22.1%, despite leading in overall cultivation area and yield.

Palakkad, along with Alappuzha, Thrissur, and Kottayam, accounted for 82.5% of Kerala’s total rice output.

However, Alappuzha, Kozhikode, and Kannur bucked the trend, registering production increases, with Alappuzha experiencing a notable rise of 10,795.6 tonnes.

A senior official from the Kerala State Planning Board told South First that an analysis of seasonal cropping trends in 2023-24 revealed a shift in rice cultivation patterns.

While the area under the mundakan (winter) crop expanded, the virippu (autumn) and puncha (summer) crops witnessed a contraction. However, production and productivity declined across all three seasons, adding to the overall decrease in rice cultivation.

Kerala has three main rice-growing seasons:

In 2023-24, the mundakan crop contributed 40% of the total paddy cultivation area, with Palakkad leading at 28,999.9 hectares. The virippu season saw 29,471.7 hectares of paddy cultivation in Palakkad, followed by Alappuzha (6,458.1 ha). The puncha crop was dominant in Alappuzha with 27,153 hectares under cultivation.

Palakkad, Alappuzha, Thrissur, and Kottayam together accounted for 81% of Kerala’s total rice cultivation area, contributing 82.5% of total production. Palakkad led in both area and production, while Alappuzha recorded the highest productivity (3,346 kg/ha), followed by Malappuram (3,231 kg/ha).

Despite an overall decline, Alappuzha, Kozhikode, and Kannur saw an increase in wetland rice production compared to 2022-23. The highest increase was recorded in Alappuzha, where production rose by 10,795.6 tonnes. Conversely, Palakkad experienced the sharpest decline in wetland rice production, dropping 22.1% from the previous year.

In addition to wetland paddy, upland paddy was cultivated on 1,324.3 hectares, producing 3,043.5 MT with a productivity of 2,298 kg/ha. However, the area under upland paddy has been steadily declining since 2021-22.

Despite a reduction in total cultivated land, the gross irrigated area for paddy in Kerala saw an increase from 1.53 lakh hectares in 2022-23 to 1.6 lakh hectares in 2023-24.

Historically, the state had around five lakh hectares dedicated to paddy cultivation, with multiple cropping cycles pushing the total cultivated area to 8.81 lakh hectares during the 1970s.

However, the present scenario tells a different story, with the total area under paddy cultivation shrinking to just 1.78 lakh hectares in 2023-24.

The steady decline in rice farming raises critical concerns, especially in the context of Kerala’s shifting dietary preferences, agricultural policies, and environmental factors.

Tackling this issue requires a comprehensive strategy, including policy reforms, financial support for farmers, and sustainable agricultural techniques to safeguard food security and uphold the livelihoods of those engaged in rice cultivation.

Dr C George Thomas, former Chairman of the Kerala State Biodiversity Board, pointed out that multiple factors contribute to the rapid decline in Kerala’s paddy cultivation.

A key reason is the growing promotion of natural, organic, and traditional farming practices, which discourage the use of chemical fertilisers.

”There is a widespread public perception that chemical fertilisers are harmful, and the Kerala Agriculture Department appears unaware of the consequences of this mindset. A major concern is the reduction in nitrogen fertiliser usage, which directly impacts productivity,” he said.

Thomas further said that despite urea being one of India’s most heavily subsidised fertilisers, Kerala’s paddy farmers are using significantly lower amounts, leading to a decline in yields.

Kerala’s most popular paddy variety, Uma, requires 90 kg/ha of nitrogen.

”While Kerala actively discourages chemical fertilisers, it remains dependent on rice imported from North Indian states, which use significantly more fertilisers. This raises a critical question: Why isn’t Kerala adopting Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) to ensure sustainable productivity while balancing environmental concerns?” Thomas asked.

Dr. Kana Sureshan, chemist and Dean at the Indian Institutes of Science Education and Research (IISER) in Thiruvananthapuram told South First that reducing chemical fertilisers is not a sound agricultural practice.

Relying solely on basic chemical fertilisers could reduce crop yield to just 20–40% of current levels, which is insufficient to sustain the population, he said.

“People are obsessed with ‘organic’ farming, but it’s largely a marketing strategy. There is no real difference between organic and non-organic food—it’s an artificial hype,” he explained.

“Unfortunately, an unhealthy narrative has taken root in Kerala, suggesting that scientific farming causes cancer and other diseases. This chemophobia is exaggerated in India, largely fueled by media narratives and organic farming advocates,” Sureshan said.

He argued that if organic farming were to be fully adopted, at least 50% more cultivable land would be required to meet current food demands. This would necessitate deforestation, which contradicts environmental conservation goals. He criticised the government’s support for organic brands, calling it “nonsense” and a misuse of taxpayers’ money.

“Despite our claims of high literacy and educational achievements, we are largely science-illiterate. We romanticise old practices without questioning their scientific validity. Just because something is traditional doesn’t mean it is inherently superior. Where do we draw the line? Should we revert to bullock carts instead of cars, or caves instead of houses,” he questioned.

Commenting on Kerala’s promotion of millet cafes, he remarked, “Bamboo mats and millet puttu (steamed rice/wheat cakes) are being glorified as part of our ‘tradition,’ but a government with a modern outlook should not impose such regressive ideas on daily life. It’s fine to showcase traditions for tourism, but not as a regular practice.”

Sreelakshmi Ajesh, an entrepreneur from Kochi, takes a unique approach to organic products.

Sreelakshmi Ajesh.

Speaking to South First, she highlighted the commercialisation of the “organic” label, which often misleads consumers.

“‘Organic’ has become a brand, and unethical businesses exploit it to charge exorbitant prices. For instance, a so-called organic store sells carrots for ₹90 per kg, while the same carrots cost just ₹20-₹30 in a local market,” she said.

“Many, especially the elite, buy from branded organic stores to maintain a certain status. Meanwhile, common people often shy away from organic products due to their high price,” she explained.

Sreelakshmi said she ensures affordability by directly sourcing from organic farmers and leveraging social media for marketing, eliminating intermediaries.

Syam S. Pillai, a paddy farmer from Alappuzha, echoed concerns about misconceptions surrounding chemical fertilizers.

“When we use chemical fertilizers, people look at us like we’re spreading cancer. But for a healthy crop and good yield, it is essential. Many blindly chase organic products, believing they hold some magical benefit. This is a misconception,” he told South First.

He opined that the government must educate people about the role of chemical fertilisers. “Otherwise, Kerala’s unwarranted fear of fertilisers will continue, harming farmers in the long run,” he warned.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).