Published Feb 16, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Feb 16, 2025 | 10:49 AM

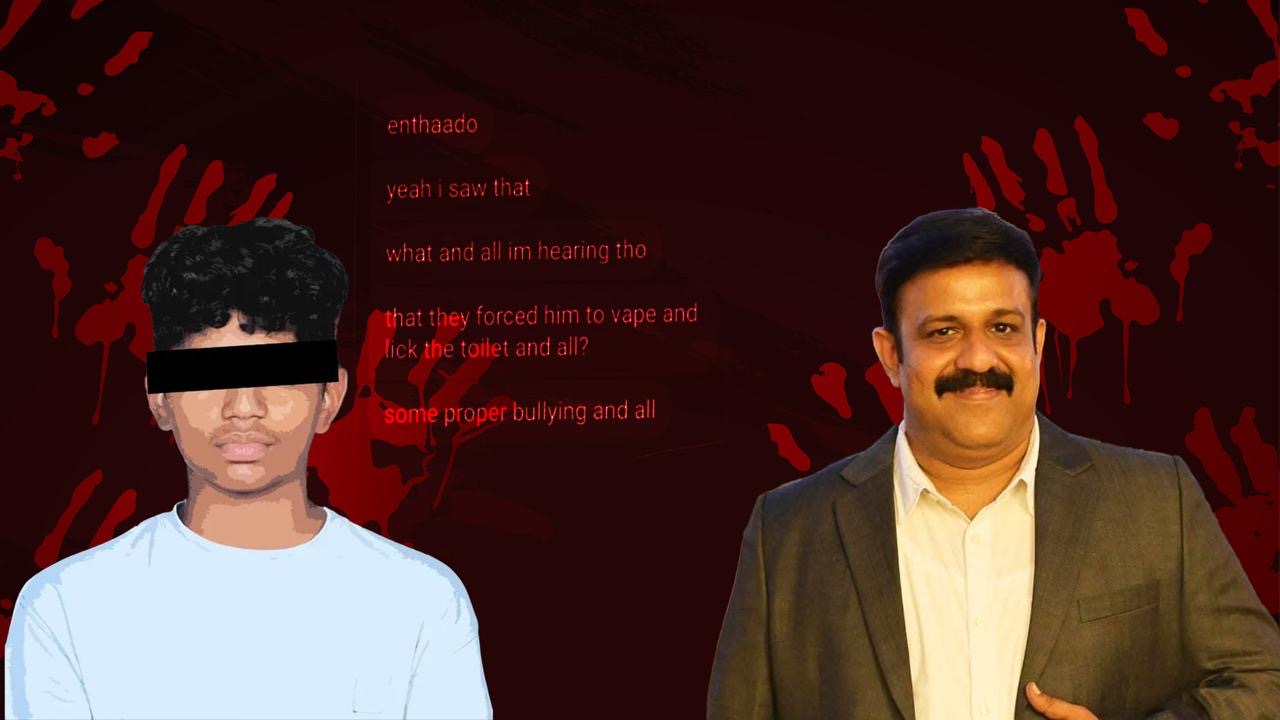

Kochi boy Mihir Ahammed’s death by suicide has ignited in Kerala discussions, ranging from the role of anti-ragging cells in schools to the influence of family environments on children’s mental well-being.

However, one crucial yet often overlooked topic remains: Are adults aware of children’s rights in India? While the law guarantees strict protection for minors, awareness and enforcement of the norms remain inconsistent.

In a conversation with South First, High Court lawyer and criminologist Advocate AV Vimal Kumar delves into the nuances of juvenile justice and the legal safeguards for children.

Q: Mihir Ahammed’s death has raised several critical questions. the most pressing being a lack of awareness among adults about laws related to children. Can you explain what juvenile justice is?

A: The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, ensures both justice and care for children. The first law for children in India was enacted in 1960 and was called the Children’s Act. Later, in 1986, it was amended and renamed as the Juvenile Justice Act. In 2000, the name was changed to the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, with the key amendment being the inclusion of “care and protection” for children.

Subsequently, in 2015, the law was further amended and named the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015. The main reason behind the 2015 amendment was the Nirbhaya case and related issues.

According to this law, a child is defined as any person below the age of 18, with no gender distinction—both boys and girls are considered children under its definition. The reason for having this law is that if children are punished like adults, they may turn into criminals after completing their sentence.

Therefore, instead of focusing solely on punishment, the law emphasizes on their reformation. This is why Parliament enacted a special law for children in our country.

Q: Children bound to delinquency is not the only scenario, some children need protection too. In Mihir Ahammed’s issue, the accused are also children (the deceased boy’s mother has claimed that an adult, too, was involved). So how does the law differentiate such cases?

A: In legal terms, children are classified into two categories: Children in Need of Care and Protection (CNCP) and Children in Conflict with Law (CCL). A Child in Need of Care and Protection refers to those who are vulnerable due to various circumstances.

This includes victims of child labour, child beggary, trafficking, drug abuse, and child marriage. It also encompasses homeless children, street children, those who have been abandoned, surrendered, or have run away from home. Additionally, children who have been abused or exploited by their parents or guardians, those who are mentally or physically challenged, and those affected by natural calamities or armed conflicts, victims of child marriage, etc., fall under this category.

Q: Nowadays, we no longer use terms like “child criminal.” Is there a reason behind this? How does the law treat such children?

A: CCL (Child in Conflict with the Law) is the term used for a child who has committed a delinquency. Earlier, terms like “child criminal” were used, but the latest amendment introduced “CCL” to describe any child under 18 who has committed an act against the law. In the case of adults, we use the term “accused.”

The aim of the Juvenile Justice Act is not to punish children but to reform them, which is why such terminology is used in the law. Juvenile justice delinquencies can be categorized into three types:

Heinous offences: Crimes such as murder and rape, or any offence with a punishment of more than seven years of imprisonment (for majors).

Serious offences: Crimes punishable by imprisonment ranging from three to seven years (for majors).

Petty offences: Crimes punishable by imprisonment of up to three years (for majors).

Q: In many situations, the police may need to interact with children. How should officers handle such cases?

A: Children must never be arrested, as per the Juvenile Justice Act. Instead, police should bring them in without uniforms, handcuffs, or police jeeps. FIRs are only allowed for heinous crimes or if linked with adult criminals. Otherwise, a Social Background Report (SBR) is prepared.

Children, whether in conflict with the law or victims, must be treated with care. Police stations should have child-friendly spaces, or preferably, avoid bringing them in. Interrogation is only allowed from 6 am to 6 pm, in the presence of parents or guardians. If needed, children may be sent to observation homes, ensuring their dignity and rights are protected.

Q: Normally, major accused individuals are produced in court, but where should a child be presented if they commit a delinquent act?

A: The police must produce a Child in Conflict with Law (CCL) before the Juvenile Justice Board (JJB) rather than a regular court. The JJB is chaired by a Principal Magistrate and includes two additional members, one of whom must be a woman. Each board serves a term of three years.

Unlike a conventional courtroom, the JJB maintains a child-friendly environment. Trials must be completed within four months. Additionally, the police are not permitted to accompany the child in a manner that visibly indicates law enforcement presence, such as in uniform or with other formal signs of the police force.

Q: If delinquency is proven under the law, what legal options are available to the child, including bail and other remedies?

A: In normal circumstances, the Juvenile Justice Board (JJB) can grant bail to a child without requiring any surety. However, in rare cases, the board may reject bail.

This can happen if there is a risk of the child being influenced or exploited by adult criminals, if the child faces life-threatening situations, or if the child is identified as someone likely to commit a heinous crime. In such cases, the child is sent to an observation home.

Q: What types of verdicts can the Juvenile Justice Board (JJB) deliver?

A: One is admonishment. Another one is group counseling with parents and family members. They can also be assigned to community service.

A fine can be imposed too. They can also be released on the surety of their parents. In some cases, children are sent to special homes for three years for reformation.

Q: Unfortunately, like the police, the media also needs to interact with children. What should the media take care of when reporting about children?

A: Section 74 of the law strictly prohibits the disclosure of any information that could reveal the identity of a child. Media outlets are not allowed to report any details, either directly or indirectly, that may compromise a child’s identity.

Violating this provision is a punishable offense, carrying a penalty of up to six months of imprisonment, a fine of up to ₹2 lakh, or both.

Q: Recently, complaints against teachers for punishments and scolding have been increasing. What should parents and teachers keep in mind while dealing with a child?

A: Recently, there have been numerous complaints of teachers being accused of physically and mentally abusing students. While most of these complaints are genuine, some may be baseless allegations made by children. However, Section 75 of the Juvenile Justice Act clearly states that any individual in a position of guardianship who harms a child is committing a punishable offense.

This can lead to a fine of up to ₹3 lakh. Teachers should be aware that any form of mental or physical harassment against a child is taken very seriously under the law.

Q: One of the latest trends is that when we see a child with a stranger, we immediately take pictures and circulate them through social media, possibly with the intention of safeguarding the child. Is this the proper way to handle such situations?

A: This is an important issue. We often see videos with captions like “maximum share,” but instead of reporting the situation to the authorities, people focus on making the content go viral. Whether this happens out of ignorance or a desire for online attention, it is deeply problematic.

If we come across a child in such a situation, the right course of action is to immediately inform the authorities or present the child before the Child Welfare Committee.

Q: Can you explain Child Welfare Committees?

A: The Child Welfare Committee operates in every district, ensuring the care and protection of children. It oversees all matters related to child welfare, including adoption.

The committee consists of four members, one of whom serves as the chairperson. Among the remaining three members, at least one must be a woman, and another must be a child expert.

Q: We discussed children in need of care and protection, but what are the places where they are sent for support?

A: If a child is brought before the Child Welfare Committee, they take over the child’s care. The child is either sent back with parents or sponsors if available or placed for adoption. If none of these options are possible, the child is sent to a children’s home.

In the children’s home, the child’s care, protection, education, development, and rehabilitation are ensured. After turning 18, they are admitted to aftercare facility centers and provided with labor skills. The child can stay there until the age of 21. After that, they can go out and live independently.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).