Published Oct 11, 2025 | 1:12 PM ⚊ Updated Oct 11, 2025 | 1:12 PM

The Court described the action as “a sheer exercise of land grabbing” and noted that it was done without proper inquiry and in violation of due procedure.

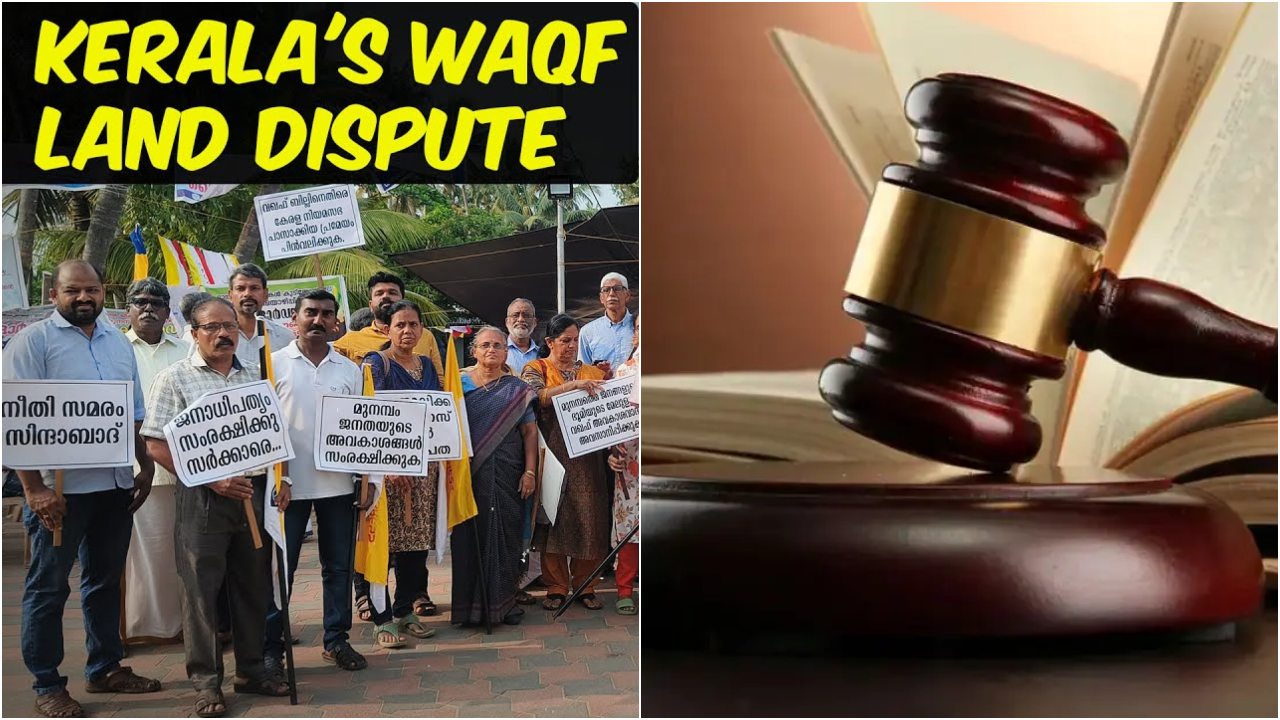

Synopsis: The Kerala High Court ruled that the 1950 Munambam endowment is a gift deed, not a Waqf, lacking permanent dedication. The court criticized the Kerala Waqf Board’s 2019 declaration as “land grabbing” after a 69-year delay, deeming it arbitrary. The state isn’t bound by this declaration, and a government inquiry commission was upheld to address the dispute involving 600 families.

In a landmark ruling that offers major relief to hundreds of families whose lives have long been in limbo, the Kerala High Court has held that the 1950 Munambam endowment executed by Mohammed Siddique Sait in favour of the Farooq College Managing Committee is not a Waqf deed but a simple gift deed.

The Division Bench ruled that the deed lacked the “permanent dedication” required to constitute a Waqf under law, effectively nullifying the Kerala Waqf Board’s 2019 declaration of the land as Waqf property.

The verdict is expected to have wide-ranging implications for Waqf property disputes across Kerala, particularly those involving delayed or unilateral declarations.

The court closely examined the 1950 deed and found that it did not fulfil the essential requirement of permanent dedication as defined in the Waqf Act of 1923, the Waqf Act, 1954, and the Central Waqf Act, 1995.

“In all the enactments, the common feature about the definition of ‘waqf’ has been that there must be ‘permanent dedication’ by a person professing Islam of the property to be treated as waqf. ‘Permanent dedication’ implies creation of an absolute inalienable interest which is non-reversionary in nature, in the property by the donor in favour of the donee,” the Bench comprising Justices Sushrut Arvind Dharmadhikari and Syamkumar V M noted.

Relying on cases like Maharashtra State Board of Wakfs v Yusuf Bhai Chawla & Ors. and Nawab Zain Yar Jung & Ors. v Director of Endowments & Anr., the court held that a valid waqf requires unconditional and perpetual dedication of property for religious, pious, or charitable purposes, with ownership vesting in God and no provision for alienation.

The 1950 document permitted the Farooq College Management to sell, lease, or otherwise transfer the property for educational or charitable purposes. The deed also contained a reversion clause, allowing the property to return to the donor or his successors if any portion remained unsold.

The Bench further observed: “Permanent dedication was never reflected in the endowment deed, wherein the beneficiary was not only entitled to sell the property, but also utilise the sale proceeds for themselves and there was a specific provision of reversion of the property… such recitals cannot be treated as amounting to permanent dedication.”

The Court thus concluded that the deed was “a simple gift deed in favour of Farooq Management” and did not qualify as a waqf deed under any of the Waqf enactments.

The Division Bench also came down heavily on the Kerala Waqf Board (KWB) for declaring the property as waqf in 2019 — a full 69 years after the original endowment.

The Court described the action as “a sheer exercise of land grabbing” and noted that it was done without proper inquiry and in violation of due procedure.

“The question is, therefore, whether the Court can keep its eyes shut to such a palpable illegality and blatant arbitrariness on the part of KWB of having woke from deep slumber after 69 years and declaring entire parcel of property as waqf… The answer is clearly ‘NO’,” the Bench remarked.

The Court observed that neither the donor’s heirs nor the college authorities had treated the property as Waqf for seven decades, and KWB’s unilateral declaration was unsustainable in law.

The court noted that from 1950 to 2019, the KWB didn’t took ant effort for a proper survey and quasi-judicial inquiry involving all stakeholders which was mandatory before declaring any waqf.

But after an “inordinate delay” of nearly 70 years it acted, which the bench said rendered the entire exercise unreasonable and not binding on the state.

It also observed that the Board appeared to be eyeing the property, which had gained high commercial value over the years.

The Bench further pointed out that the property in question was not listed in the 1962 gazette notification under Section 5 of the Waqf Act.

If the Board or any other party was aggrieved by the omission, the law required them to file a dispute under Section 6 within a year of notification.

Instead, the plaintiff questioned the non-inclusion after more than 50 years, by filing the suit only in 2013.

The court found this delay unjustified.

The Court underlined that statutory powers must be exercised within a reasonable time.

The Waqf Board’s failure to act for 69 years — during which multiple third-party ownership and occupancy rights were created — rendered its declaration of the land as waqf “arbitrary and lacking in bona fides.”

The court observed that the value of the land had increased substantially over the years, making the 2019 declaration appear as an attempt to “wrest control” of the property rather than protect a legitimate waqf.

The Bench noted that no survey under Section 4 of the Waqf Act had been conducted prior to issuing the notification under Section 5 in 1959.

In the absence of such a survey, mere issuance of notification does not amount to valid declaration of waqf property.

This lack of procedural compliance further weakened the Waqf Board’s claim.

While terming the Waqf Board’s action illegal and unsustainable, the Division Bench refrained from quashing the 2019 declaration.

Instead, it clarified that the state government is not bound by the Board’s belated declaration and may proceed with measures to protect the interests of bona fide purchasers and occupants.

The Division Bench also set aside a single judge’s 17 March order that had quashed the state’s decision to form a Commission of Inquiry to examine the land dispute.

The division bench held that the single bench’s view was erroneous.

The government had argued that the commission, headed by retired High Court judge Justice CN Ramachandran Nair, was merely a fact-finding body with no power to decide ownership or title.

The dispute, the state said, had escalated into a law-and-order issue involving around 600 families, and the commission’s role was to explore amicable solutions.

“The writ appeals are allowed,” the Bench declared, thereby upholding the government’s power to constitute the commission.

Further, giving a shot in the arm for the state government, the bench ruled that, “Having held that the declaration of the subject property is not at all binding on the state government, the Inquiry Commission’s report may actually enable it to decide finally whether to acknowledge the declaration/registration of the subject property as a waqf or not.”

The disputed land, originally measuring 404.76 acres, was gifted in 1950 by Siddique Sait to Farooq College.

By then, several families were already residing on the land.

Over the decades, portions of the property were sold to residents without reference to any Waqf status.

Due to sea erosion, the land area has reportedly shrunk to 135.11 acres.

The Waqf Board’s 2019 declaration of the land as their property created panic among nearly 600 families, who fear eviction and are unable to pay land tax or secure mutation of their property.

(Edited by Amit Vasudev)