Published Jan 06, 2026 | 3:22 PM ⚊ Updated Jan 26, 2026 | 8:50 AM

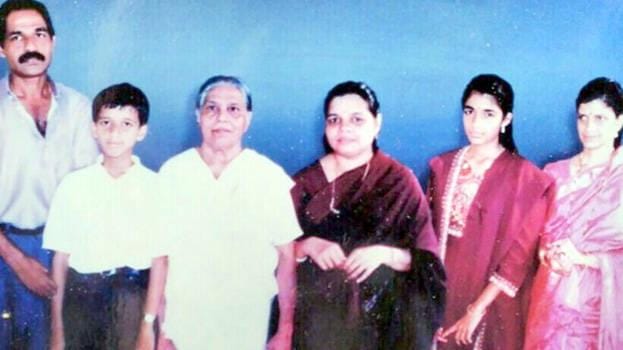

The Manjooran family, victims of the January 2001 massacre.

Synopsis: It has been 25 years since six members of the Manjooran family were killed on a winter night at their residence in Aluva, Kerala. Police arrested MA Antony for the brutal massacre, and he was sentenced to the gallows, which was later commuted to life imprisonment. Though Antony has been jailed, and years have passed, questions about the massacre remain unanswered.

On a Saturday night 25 years ago, Aluva in Kerala’s Ernakulam district, went to sleep peacefully as usual. Sunday, too, seemed ordinary, and life went on, oblivious to a horrific act that remained hidden within the confines of the house throughout the day.

Monday, 8 January 2001. The municipality shuddered up to a cold winter morning that reeked of blood. Amidst the shock that numbed the conscience, the realisation soon dawned that the intervening night of 6 and 7 January 2001 had altered the psychological landscape of Aluva.

It didn’t take an entire night for fear to grip Aluva upon the River Periyar that meanders westward towards its final destination. Instead, it took just three hours.

In those eventful three hours, six members of the Manjooran family were murdered while the municipality slipped into sleep, turning a lively household into a scene of unspeakable horror — a crime so savage that it shattered Aluva’s sense of safety.

The spine-chilling incident’s effect was immediate. In the days and weeks that followed, streets fell silent after sunset, darkness seemed darker where imaginary shadows lurked, those who dared felt their feet unusually heavier, and cinema halls cancelled second shows.

Nights become colder and quieter, slashed by the occasional, ominous and distant hoots of unseen owls that keep sleep away. Fear has become a constant, fuelled by baseless theories that were lapped up without question.

The answer to the major question, however, was miles away, beyond the blue expanse of the sea, in a foreign land.

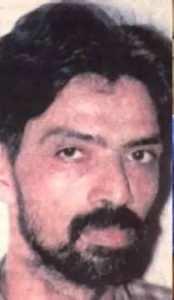

The mystery unravelled gradually, and MA Antony alias Antappan soon became the most fearsome and hated individual in Kerala.

Antony was later convicted and sentenced to death for the massacre. The punishment was later commuted to life imprisonment.

Even after a quarter-century, the Manjooran family massacre remains one of Kerala’s most chilling crimes — raising questions that still refuse to fade.

One of the most brutal crimes committed on the intervening night of 6 and 7 January 2001 shattered the peace of the normally quiet municipal town of Aluva.

MA Antony alias Antappan (File pic)

While the town slept, Manjooran House—situated in the heart of Aluva—witnessed an unimaginable carnage.

Later, the prosecution said Antony, desperate for money to fund his travel abroad and enraged by the refusal of financial help from the Manjooran family, unleashed a meticulously planned killing spree.

Around 10 pm on 6 January, he allegedly murdered Kochurani and Clara using a combination of knife, axe, electrocution and strangulation.

Instead of fleeing, he waited with the bodies in the silent house for the return of the remaining four family members: Augustine, his wife Mary, and their children Divya and Jesmon, who had gone for a film.

Oblivious of death waiting for them, the family returned home from their weekend outing around midnight and was killed.

The prosecution later alleged that the murders were cold-blooded, executed with chilling precision, and Antony ensured no trace of life remained before leaving the scene.

A house that was full of life at 10 pm turned into a blood-splattered graveyard within three hours.

In court, Antony pleaded innocence.

Police were informed of the crime more than 24 hours after Kochurani and Clara were killed.

Around 11.30 pm on 7 January, Joseph alias Rajan approached the Aluva Police Station. He reported information that his sister Mary, her husband Augustine alias Baby, their children Divyamol and Jesmon, and Augustine’s mother Rahel and sister Rani (Kochurani) had been murdered at Manjooran House.

Sub-Inspector NV John recorded Joseph’s statement that revealed a desperate search for the family before the gruesome discovery.

Joseph stated that Mary had not visited his house that morning as planned. Repeated phone calls went unanswered, and enquiries through relatives revealed that the house was locked and the family was missing.

The house, in fact, was not locked.

Assuming the family might have gone to some function, the relatives waited until night. Around 10 pm, Joseph and his brother-in-law, Sunny, went to Manjooran House and found the door partly open.

Milk packets and newspapers from the morning lying untouched on the verandah aroused their suspicion. The men entered the house, and the living met the dead. A flashlight they used showed Jesmon lying in a dried-up pool of clotted dark red.

Overcoming the initial shock, they searched for the remaining family members. Their calls evoked no response. They found Divyamol lying face down in another room, Mary slumped on the floor, and Augustine lying on his back—all still, silent and slain.

They immediately informed relatives and rushed to the police.

The murders marked the beginning of a trial that would deeply scar Kerala’s collective conscience.

Fear gripped the region as rumours ran wild in the days following the mass murder.

Whispers of Maoist involvement and terrorist links grew louder and spread rapidly, each rumour with gruesome details adding a fresh shudder to the already shocked conscience of the state.

Despite intense scrutiny, the police initially failed to secure any decisive breakthrough, leaving the case shrouded in mystery.

According to investigators, the turning point came during a review meeting when a member of the investigation team suggested a simple but unconventional approach: if the crime had taken place in the wee hours, the focus should shift to identifying who was awake at that time and who had been moving around the neighbourhood.

Acting on the idea, police patrol teams were deployed in the area during the early morning hours for several consecutive days.

A patrol team noticed an elderly woman regularly passing through the area before dawn. When questioned, she lashed out at the police, expressing anger over their failure to catch the culprits.

But as the conversation continued, investigators sensed something important.

The woman revealed that she regularly attended the morning prayers at the church. When asked whether she had seen or heard anything unusual on the day of the crime, she mentioned a name: Antony.

Police records soon revealed that Antony had already flown to Dammam in Saudi Arabia.

Further checks raised additional red flags—he had cleared his debts just before leaving the country. For investigators, the pieces began to fall into place.

Antony had been in contact with his wife through a telephone in the neighbourhood. Investigators discreetly instructed those aware of the calls not to alert his wife but to inform the police instead.

Through the calls, the police managed to trace his communication pattern and contacted his sponsor in Saudi Arabia. Investigators eventually spoke to Antony indirectly through his wife.

During the conversation, Antony admitted that he had visited the house on the evening before the murders. To bring him back to India, the police used the help of the recruiting agent who had facilitated his overseas job.

Antony was told that a major mishap had occurred at his home, prompting him to immediately fly back home from Dammam via Mumbai.

He flew down into the waiting police net. Sustained interrogation made him sing.

According to the police, Kochurani had earlier pledged money to Antony. However, when he later demanded it back, she allegedly refused.

Enraged, Antony pushed her during an argument, and her head hit a wall—triggering the chain of events that led to the mass murder.

Antony was a distant relative of Augustine.

The conviction of Antony rested entirely on circumstantial evidence marshalled by the prosecution, including motive, his alleged presence near the victims’ house on 6 and 7 January, his absence from his residence that night, recoveries made under Section 27 of the Indian Evidence Act, fingerprints, scalp hair, and both judicial and extra-judicial confessions.

The Crime Branch CID initially probed the case before it was handed over to the CBI.

In 2005, a CBI court found Antony guilty under Sections 302 (murder), 379 (theft), 449 (house trespass) and 201 (destruction of evidence) of the IPC and awarded him the death penalty.

The Kerala High Court confirmed the sentence in 2006, and the Supreme Court upheld it in 2009.

The President rejected Antony’s mercy petition in 2015.

However, in a significant turn, the Supreme Court in December 2018 commuted his death sentence to life imprisonment, observing that none of the courts had examined the possibility of his reform or rehabilitation.

The review bench noted the absence of material to brand Antony a hardened criminal and held that his dire socio-economic condition, though irrelevant to guilt, was crucial in deciding the sentence, underscoring a critical lapse in the application of the “rarest of rare” doctrine.

Antony, currently out on bail, is serving his sentence at the Open Prison and Correctional Home, Nettukaltheri, Thiruvananthapuram.

Antony had consistently alleged that the investigation was biased and incomplete, and it deliberately ignored crucial leads that would have established his innocence.

From the outset, the case records did not contain any circumstances conclusively linking the appellant to the crime.

Yet, this line of inquiry was not pursued.

Instead, the investigating agency appeared determined to project the case as solved, allegedly turning the appellant into a convenient scapegoat.

One of the most significant issues raised relates to forensic evidence. According to a testimony, human spermatozoa were detected in Kochurani’s pubic hair and vaginal swab.

These samples were subjected to DNA analysis after collecting the appellant’s blood, and an examination report dated 27 December 2002 categorically ruled out the appellant as the source of the male DNA.

The inquest report further noted that Kochurani’s skirt was rolled up and a white fluid was present on her private parts, indicating fresh sexual intercourse.

However, the prosecution attempted to dilute this evidence by suggesting it could have resulted from earlier consensual intercourse—an explanation questioned by the defence, as biological traces would not ordinarily persist after several days.

Another neglected line of investigation concerns at least 10 bloodstained footprints found inside the house.

The prosecution claimed the impressions were unclear, later advancing a questionable theory that the accused was wearing socks, allegedly recovered later, to explain the absence of usable footprints.

The defence argued that it was a fabricated narrative to mask investigative failures.

Further, despite multiple weapons being used—an axe, two knives, a chopper and a double knife—no fingerprints were lifted from them.

While fingerprints recovered from the house were partially matched, the presence of bloodstained prints allegedly linked to the appellant could not be corroborated by blood grouping.

Adding to these doubts, an Alappuzha-based NGO, Friends of Renewal India, later highlighted serious investigative gaps, noting that despite DNA evidence excluding the appellant, no further probe was conducted.

The NGO also cited letters written by the convict from prison alleging coercion, including threats against his family, to force a confession—deepening the controversy surrounding the case.

Today, after 25 years, the smell of blood still lingers as several questions remain unanswered.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).