Published Dec 05, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Dec 05, 2025 | 9:00 AM

Pamba river waste dumping.

Synopsis: A non-existent custom is polluting the Pamba River in Kerala — the lifeblood of the state’s spiritual and cultural identity for centuries. Devotees, after having darshan at Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple, are throwing away their used clothes and beaded malas into the river is an offering, which subsequently stealthily mutated into a “ritual”.

Pamba — Kerala’s third-longest river and revered as the southern Ganga — has been the lifeblood of the state’s spiritual and cultural identity for centuries.

Rising from the mist-laden Pulachimalai hills of the Peermedu plateau in Idukki and cascading through forests enriched with rare medicinal flora, this sacred river carries legends, prayers, and history in every ripple.

Yet, today, the same waters that once symbolised purity are choking on an unexpected pollutant — and that too generated by devotees after having darshan at Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple —used clothes and beaded malas.

And this non-existent custom — never sanctioned by scripture, never part of tradition — took root in the pilgrim psyche sometime ago, in which they believe that flinging their used clothes and beaded malas into the river is an offering, which subsequently stealthily mutated into a “ritual”.

What began as an isolated act a few years ago has ballooned into a toxic habit, transforming the holy Pamba into a dumping ground in the name of devotion.

Heaps of garments fished out from Pamba river.

The practice of discarding dhoties and other apparel in the sacred river Pamba has once again come under sharp scrutiny — this time amid a massive pilgrimage surge during the Mandala-Makaravilakku season, with the number of Sabarimala devotees already crossing 15 lakh.

The issue garnered renewed attention after the Kerala High Court issued a stern directive to the Travancore Devaswom Board (TDB), declaring that abandoning clothes in the river is not an essential religious practice and has no scriptural basis linked to the Sabarimala darshan.

On 29 November, a Division Bench comprising Justices Raja Vijayaraghavan V and KV Jayakumar pulled up the Board for failing to curb environmentally destructive customs that are turning Pamba into a dumping ground.

The court observed that the ritualised disposal of garments — long assumed by many devotees to be part of the pilgrimage — seriously compromises the sanctity and ecology of the holy river.

In a comprehensive order, the Bench directed the TDB to prepare and implement a detailed protocol aimed at safeguarding pilgrims’ health, safety, and movement.

The guidelines must include:

Further, the court insisted that the protocol must categorically prohibit the dumping of dhoties or any apparel in Pampa, stressing that the Board should actively sensitise pilgrims on the ecological implications of such actions.

The judges also mandated that the TDB publicise the protocol widely — via its official website, print and electronic media, banners, public announcements, and SMS alerts — in multiple languages.

The Board has been given seven days from receipt of the judgement to complete this exercise.

With lakhs continuing to throng the hill shrine this season, the high court’s intervention signals a decisive move to align religious practice with environmental responsibility — potentially marking the beginning of the end for a tradition that has outlived its spiritual relevance and threatens a river that remains central to Sabarimala’s identity.

Nearly ten years ago, in 2015, the Kerala High Court raised a red flag on the same issue.

In a strongly worded order, then, a division bench led by Justice Thottathil B Radhakrishnan declared that throwing clothes into water bodies near the shrine was not just undesirable but a punishable offence under the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974 — an act that carries imprisonment of up to six years depending on the severity of the pollution caused.

The court reminded that the right to practise religion cannot override public order, morality, or health.

Following the verdict, the then-special commissioner K Babu reiterated that discarding garments in the river had no scriptural sanction and was never a part of Sabarimala traditions. He warned that not only the individual polluter, but also those accompanying or encouraging such acts, could be prosecuted.

The high court categorically stated that there exists no religious tenet requiring devotees to abandon clothes after darshan. However, despite the stern legal tone, little has changed along the riverbank.

Allegations persist that the directives remain poorly enforced, with offenders often let off with mere verbal warnings instead of prosecution.

A decade later, the Pamba continues to bear the burden of “ritual” waste, its sanctity eroded not by faith, but by the failure to act.

A notice board at Pamba.

Tons of garments and even beads are being removed from the Pamba river every season, according to a TDB official, who calls it a worrying and misguided trend fast gaining ground despite repeated warnings.

Notice boards requesting devotees not to dump clothes are displayed across the site, yet many choose to ignore them, he said.

The official clarified that, contrary to popular belief, Sabarimala has no tradition or custom that requires devotees to discard clothes worn during the pilgrimage or after darshan.

“We have only heard of such practices in certain temples in Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Puducherry, and a few other regions. Someone — or a group — from outside may have introduced this idea here. It spread by word of mouth, and now many assume it’s an age-old Sabarimala custom,” he explained.

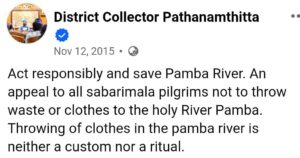

An appeal made by Pathanamthitta District Collector in 2015.

The belief behind the practice elsewhere, he said, is that clothes used during a pilgrimage absorb spiritual energy, sins, impurities, or the intense divine presence of the sacred site.

Devotees fear that taking these garments home may bring negative energy, while others see it as disrespectful once the pilgrimage is complete. “But this is not a part of Sabarimala’s tradition,” the official reiterated.

To combat the issue, the TDB has deployed volunteers along the ghats to dissuade devotees and another team to retrieve garments dumped in the river.

The board has also contracted a Tamil Nadu-based company to handle the large quantities of clothes collected from Pamba.

As the volume of discarded items continues to rise, officials warn that the baseless practice poses not just a cultural distortion but a growing environmental threat to one of Sabarimala’s most sacred natural spaces.

What appears to be a senseless act is, in reality, disrupting one of the state’s most ecologically sensitive river systems.

The Pamba sustains vast stretches of riparian vegetation — green corridors that stabilise soil, prevent erosion, store carbon, and support diverse wildlife. This natural buffer is crucial for maintaining the river’s health.

However, textiles, especially synthetic clothes, introduce microfibres, dyes, and chemical residues into the water.

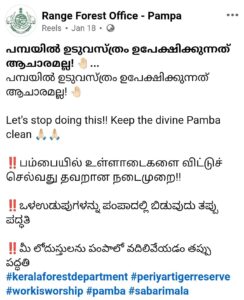

Forest Range Office-Pamba’s appeal.

A senior Kerala State Pollution Control Board official warns, “Synthetic garments don’t disappear once submerged. They release fibres and chemicals for years, turning the Pamba into a slow-moving toxic stream.”

These substances reduce oxygen levels, smother aquatic plants, and alter the chemical composition of the river, affecting organisms from plankton to fish.

Over time, the official said, this contamination seeps into the food chain, endangering not just the river’s inhabitants but also the humans who depend on its water.

The ecological stakes are compounded by the presence of the Periyar Tiger Reserve upstream.

The reserve, part of the largest tiger conservation landscape in the southern Western Ghats, depends on the Pamba and Azhuta rivers for sustenance.

Pollution in these waters has implications far beyond aquatic life, potentially impacting iconic species such as elephants, tigers, otters and the Nilgiri langur.

Unless dumping practices stop and waste-management awareness grows, the river’s sacred symbolism may soon be overshadowed by irreversible ecological loss.

(Edited by Muhammed Fazil.)