Published Jul 17, 2024 | 4:00 PM ⚊ Updated Jul 17, 2024 | 4:00 PM

Munnar bazaar during the Great Flood of 1099

“The temple was on the highest point in the village. The deity stood submerged, neck-deep. There was water all around,” Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai began his short story, Vellapokkathil (In the Flood).

The story narrated the poignant tale of a dog — forgotten, ignored, and abandoned — even as its owner Chennaparayan escaped with his family in a canoe.

A cat that gave company, and played hide-and-seek with the dog had sneaked into the canoe that sailed to dry land and safety. The famished dog stood guard, fighting thieves, till death floated in.

The short story, published in 1935, was Jnanpith winner Thakazhi’s recollection of the devastating floods that submerged Kerala in 1924. Old-timers call it the ‘Great Flood of 1099’ (Thonnutti-onpathile vellapokkam), referring to the year in the Malayalam calendar.

The flood was so savage that deities, anthropomorphized, as Thakazhi had recollected, stood helpless in neck-deep water.

It seemed dystopian, yet real. The flood did not spare even the high ranges of Munnar — located 6,000 feet above sea level — the town submerged for the first time. Bloated corpses and carcasses floated together. The flood had erased the line differentiating man from animal.

A submerged Munnar in July 1924. (Sourced)

The flood that ravaged the then-princely states was unlike anything witnessed before. Though whispers of the devastation linger, a complete picture remains elusive.

As the state marks its centenary, South First revisits the devastating event and uncovers the forgotten chapter in Kerala’s history.

Floods seldom come alone. They bring with them a set of woes, testing the endurance, mettle, and patience of people — and animals, like Chennanparayan’s dog.

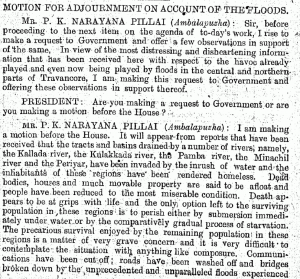

The plight reflected in Ambalapuzha member PK Narayana Pillai’s voice in the Travancore Legislative Council (TLC) on 25 July 1924.

“Death appears to be at grips with life and the only option left to the surviving population in these regions is to perish either by submersion immediately under water or by the comparatively gradual process of starvation,” he said, moving an adjournment motion.

An excerpt from the adjournment motion moved on 25 July 1924. (Sourced)

Pillai said the precarious survival of the remaining population in the flooded regions was a grave concern and tough to contemplate the situation with composure.

“It will appear from reports that have been received that the tracts and basins drained by several rivers, namely, the Kallada, the Kúlakkada, the Pamba, the Meenachil, and the Periyar, have been invaded by the inrush of water and the inhabitants of these regions have been rendered homeless,” he said.

“Dead bodies, houses, and much movable property are said to be afloat and people have been reduced to the most miserable condition,” he informed the House.

In another part, he said that communication links have been cut off. Roads have been washed away and bridges broken down by the unprecedented and unparalleled floods experienced in Travancore.

He demanded the House to adjourn for a week given the heavy floods in different parts of Travancore.

The flood as well as the demand for adjournment came at a time when the Budget for 1100 ME (1925) was due.

A Hoogewerf, a nominated Council member, drew attention to the grave situation in the country (Travancore).

An excerpt from the Diwan’s address on 9 March 1925. (Sourced)

“There is a big book, the budget, staring us in the face. This has been prepared under normal conditions, but the whole aspect of the country has changed. Thousands and lakhs of rupees will have to be spent on repairs of bridges and roads, culverts, etc., and more on relief work,” he pointed out.

“The whole of this budget is not worth the paper on which it is printed, as matters stand just now,” Hoogewerf tried to prioritise the matters.

Extending support to the motion, he remarked: “Are we to sit here and legislate when people are dying, when people are starving on account of the terrible havoc caused in the country by the flood? It will be like Nero fiddling while Rome is burning,” he minced no words.

“Therefore, I strongly support the motion that the House be adjourned for some future time till normal conditions are restored,” he stated.

Several other members also seconded the motion. The House was adjourned till 1 August 1924 for the presentation of the Financial Statement, 1100.

Financial Secretary to Government K George presented the Financial Statement, 1100. “We are met here under the shadow of a great calamity,” he commenced his speech.

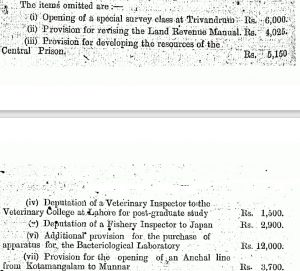

Items excluded from the Financial Statement 1100. (Sourced)

“But in the last two weeks, our country has been laid waste by floods of unprecedented magnitude. All our rivers, particularly those to the north of Quilon (Kollam), have overflowed their banks and inundated the tracts through which they flow, spreading desolation and distress to the people who live in their neighbourhood. Full details of the extent of the disaster are not yet available,” he said.

Stating that the widespread disaster must necessarily affect Travancore’s finances both directly and indirectly, George also highlighted the need for adequate provision for the relief of distress and the repairs of flood-damaged public works.

The financial secretary then informed the House that seven items had been omitted from the Budget, including sending two government officials to Lahore and Japan, respectively. Two additional provisions were included.

Those were granted to the PWD, which was raised by ₹3 lakh, for the restoration of damaged communications, bridges, and irrigation and drainage works and a provision for debt head — agricultural loans, which was raised from ₹1,50,000 to ₹5,50,000.

The additional provision of ₹4 lakhs was for advancing loans for the rehabilitation of the agricultural population in the affected areas.

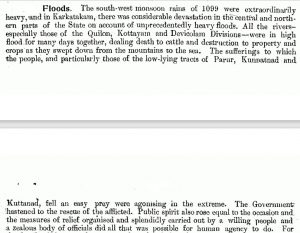

A vivid account of the floods as well as the generous donation from the public has been detailed in the Administration Report for the year 1099.

The then-Diwan T Raghavaiah presented the report. “The south-west monsoon rains of 1099 were extraordinarily heavy, and in Karkadakam ( a Malayalam month) there was considerable devastation in the central and northern parts of the state (Travancore) on account of unprecedentedly heavy floods.”

All rivers, especially those in the Quilon, Kottayam, and Devicolam (Devikulam) Divisions were in high flood for many days together, dealing death to cattle and destruction to property and crops as they swept down from the mountains to the sea.

“The sufferings to which the people, and particularly those of the low-lying tracts of Parur, Kunnatnad, and Kuttanad, fell an easy prey were agonising in the extreme,” he added.

Mentioning the relief works the Diwan said, “The government hastened to the rescue of the afflicted. Public spirit also rose equal to the occasion and the measures of relief organized and splendidly carried out by a willing people and a zealous body of officials did all that was possible for human agency to do.”

The Diwan also mentioned the relief assistance as he stated that “gratuitous relief to the extent of about half a lakh of rupees was afforded from the state exchequer, while generous public, both in and outside the state, placed a sum of over ₹64,000 at the disposal of the Central Flood Relief Committee” to immediate relief and reconstruction purposes.

Meanwhile, in the Cochin princely state, records available from the Cochin Legislative Council meetings mostly mentioned agricultural and property losses.

At Mukundapuram Taluk alone, the 1099 floods resulted in the loss of 6766.52 acres of agricultural land, worth ₹3.80 lakh.

In other data, it has been stated that a total of 122 houses were permanently damaged in Cheruthuruthi, Nedumbura, Deshamangalam, and Palloor villages.

In 2018, Kerala got visions of the Great Flood of 1099, when unprecedented torrential downpours brought it to its knees.

As Kerala has been grappling with increasingly extreme weather events, learning from past tragedies could help it build resilience and safeguard its communities.

Let this centenary be a call to action – to honour the memory of those affected, to glean valuable lessons, and to ensure equip Kerala better to face the storms ahead.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).

(South First is now on WhatsApp and Telegram)