Kerala government's Home Department insists that violence and deaths inside police stations and prisons are not human rights violations.

Published Dec 04, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Dec 04, 2025 | 9:00 AM

Kerala custodial violence RTI.

Synopsis: The Kerala Police refused an RTI question seeking the data on violence and deaths inside police stations and prisons. It was denied, saying the application does not fall under the categories of Human Rights Violation and Corruption. Similarly, in the state Assembly, the Home Department, headed by Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan, repeatedly sidestepped pointed queries on custodial torture.

Kerala takes pride in flaunting its progressive credentials and constitutional fidelity. However, peel back the veneer, and a disturbing reality confronts you.

Even as the Supreme Court repeatedly affirmed that the right to life under Article 21 extends unequivocally to every person in State custody — convict, undertrial, or detainee — Kerala’s own Home Department appears to believe otherwise.

It has adopted a stance that borders on the unbelievable: violence and deaths inside police stations and prisons, it insists, are not human rights violations.

The declaration, made in a Right to Information (RTI) plea, laid bare an institutional mindset and the political patronage that shields one of the most barbaric crimes in a civilised society — custodial violence.

This evasiveness echoed in the Legislative Assembly also, where the government either dodged questions on custodial torture or hid behind a mechanical excuse — that no “compiled data” was available.

In a move that has raised eyebrows in legal and human rights circles, the Kerala Police denied an RTI request filed by former Director General of Prosecutions (DGP) T Asaf Ali — claiming that information on custodial deaths, alleged police shootings of Maoists, missing persons, and custodial violence does not fall under the category of “human rights violations.”

The former top prosecutor had approached the State Police Headquarters on 19 September, seeking crucial data from 1 April 2016 to date, including:

The application was forwarded to the State Crime Records Bureau (SCRB) — but the reply that came on 16 October left even seasoned observers stunned.

Quoting a series of government orders, the State Public Information Officer (SPIO) of the SCRB wrote that the department is exempt from providing information under Section 24(4) of the RTI Act, except in matters related to human rights violations and corruption.

And then came the line that has since triggered outrage: “Since the information sought in this application does not fall under the categories of Human Rights Violation and Corruption, we are unable to provide the information.”

This, despite the queries explicitly relating to custodial deaths, alleged encounters, custodial violence, and serious misconduct — subjects widely recognised, even by courts, as core human rights issues.

The response is particularly jarring in the wake of repeated Supreme Court observations that, “custodial crime is perhaps one of the worst crimes in a civilised society and whenever it is established that there has been custodial violence at the hands of those who are supposed to protect the life and liberty of the citizens, that situation is enough ‘to lower the flag of civilization to fly half-mast’ because such custodial violence makes civilisation take a backward step.”

The petitioner’s attempt to access critical information regarding custodial deaths and missing persons from the SCRB was rejected by the appellate authority, who reiterated that the agency is largely exempt from the Right to Information (RTI) Act, 2005.

The appeal, filed by Asaf Ali on 22 October, was a challenge to an initial refusal to provide details such as:

Asaf Ali argued before the Appellate Authority, the Superintendent of Police, SCRB, Pradeep N Wales, that the information sought directly relates to life, liberty, and dignity, and therefore falls under the scope of human rights violations.

He cited the Proviso to Section 24(4) of the RTI Act and Section 2(d) of the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993, which defines ‘Human Rights,’ to assert that such information cannot be exempted from disclosure.

However, in an order dated 31 October, the Appellate Authority disposed of the appeal by reinforcing the exemption granted to 10 police offices, including the SCRB.

The Authority stated that the law “stipulates that only information related to corruption or information related to Human Rights violations should be replied to under sub-section 4 of section 24 of the Right to Information Act, 2005.”

By rejecting the appeal, the Authority implicitly determined that the specific details sought did not meet the criteria for information about a human rights violation that is eligible for disclosure under the proviso.

Despite the rejection, the Appellate Authority pointed out that some data is already publicly available.

The order stated that the “Numbers and details of people reported missing during the period from 1 April 2016 to date are available on the official website of Kerala Police.”

The Authority concluded by advising the petitioner that “Information that can be accessed by the public is also available on the official website of the Kerala Police.”

The decision leaves the petitioner with the option of escalating the matter to a higher forum to challenge the interpretation of what constitutes a human rights violation under the RTI Act’s exemption clause.

Speaking with South First, Asaf Ali, also a legal expert, termed the authorities’ stance “bizarre” and legally untenable.

He pointed out that both the SPIO and the First Appellate Authority erred gravely by denying information on the grounds that the State Crime Records Bureau (SCRB) is exempted under Section 24(1) of the RTI Act.

“They should have held that the information sought relates to human rights violations and is exempted under the proviso to Section 24(1) of the RTI Act, thereby entitling the applicant to receive the entire set of information,” Asaf Ali said.

He stressed that the information demanded touches upon matters of life and liberty, making it disclosable under the proviso to Section 24(4) of the Act.

“At any rate, there is no legal justification in denying such information,” he asserted. He also added that he has filed an appeal as well as a complaint before the State Information Commission.

Meanwhile, former Kerala State Police Chief Dr TP Senkumar (Retd IPS) echoed the concerns, questioning the very logic of SCRB’s exemption from the RTI ambit.

“It is puzzling why SCRB is exempted. You can seek information from the National Crime Records Bureau under RTI, but not from SCRB. This is wrong,” he told South First.

Senkumar revealed that he had, during his tenure, written to the government seeking the removal of SCRB from the exemption list — but nothing moved.

“The liability to prove human rights violation or corruption rests with the applicant, and that loophole is used to block information,” he added.

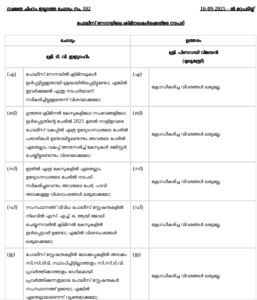

An excerpt of the response provided by Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan on questions related to criminals in the police force.

Adding to the concerns is the state government’s deafening silence inside the very temple of democracy.

In the just-concluded 14th session of the Kerala Legislative Assembly, Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan — who also oversees the Home Department — repeatedly sidestepped pointed queries on custodial torture.

Legislators seeking details on custodial deaths, torture complaints, inquiry outcomes, or disciplinary action against erring police officers were met with either terse, evasive responses or no answers at all.

The standard reply, delivered with stunning monotony, was a bureaucratic shield: “compiled data is unavailable.”

On 16 September, Ramesh Chennithala sought the names and details of police officers who have faced complaints and investigations related to custodial torture since 2016. The question was ignored.

The same day, Najeeb Kanthapuram demanded district-wise details of custodial abuses, accused officers, legal action taken, and measures proposed to prevent such torture—none of which elicited a substantive reply. Similar interventions by CR Mahesh and K Babu met the same stone wall.

TV Ibrahim asked for specifics on police officers facing criminal charges, including Station House Officers (SHOs) currently under probe. Yet again, silence prevailed.

On 30 September, Anwar Sadath requested case-wise details of police officers convicted for custodial torture since 2016 — another unanswered query. Anoop Jacob’s straightforward question on custodial deaths and police dismissals since the government assumed office also vanished into the void.

For an administration that loudly proclaims zero tolerance toward human rights violations, this evasiveness on the Assembly floor exposes something far graver than bureaucratic inefficiency: A reluctance to confront the systemic violence embedded in policing.

The refusal to even acknowledge data suggests an uncomfortable truth — Kerala’s government may not merely be failing to curb custodial brutality; it may be unwilling to admit its existence.

(Edited by Muhammed Fazil.)