Ajitha's story begins amid the fire and fury of the Naxalite movement, but it does not end in the shadows of armed struggle.

Published Apr 15, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Apr 15, 2025 | 9:00 AM

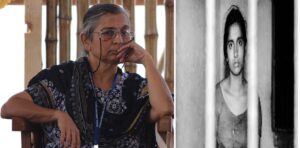

A young Ajitha after her arrest.

Synopsis: K Ajitha is not sporting her Naxalite past as a qualification. Yet, the years gone by and the hardships she had endured, failed to douse the revolutionary spirit in her. Today, she is a torchbearer of women’s rights, providing shelter and support to needy women and children at Anweshi, an NGO she has floated.

Her wide eyes looked as if they were searching for someone familiar in an unfamiliar situation. She looked like a higher secondary school student in a blouse and long skirt.

Some photographs, like the one reproduced above, showed her amid policemen. Some men craned their necks to be in the picture with the lone woman, their prized catch. In other pictures, she stood alone.

All photographs showed the young woman, K Ajitha, wide-eyed and showing no signs of weakness.

For the 1970s kids, who grew up seeing the photographs, Ajitha was the poster girl of Naxalism.

Cut back to the 1960s. Kerala had by then grabbed global attention as the first Indian state to elect a communist government through democratic means to power in 1957. Though the government was short-lived, communism had by then run its roots deep in the state, despite the mainstream party’s split in 1964.

K Ajitha.

However, a group of youngsters disillusioned with society were fuming against the existing system. They, the Naxalites, had a vision of class justice, which they felt could be achieved through an armed movement.

On 22 November 1968, around 300 Naxalites led by Kunnikkal Narayanan attempted an attack on the Thalassery police station to take over arms and ammunition. The attempt did not go as planned.

Two days later, another group attacked the Malabar Special Police camp at Pulpally in Wayanad. The camp was set up to quell a farmers’ agitation. The group also raided farms of landlords and distributed food grains to the tribal community.

The attack shocked Kerala. A sub-inspector and a wireless operator were killed in the ambush led by Arikkad Varghese.

Among the attackers were Thettamala Krishnankutty, Kurichiyan Kunjiraman, Kisan Thomman, Philip M Prasad, and Ajitha, the 19-year-old daughter of Narayanan, who had led an unsuccessful attack on the Thalassery police station 48 hours ago.

Kerala stood in disbelief as stories — many of them colourfully fabricated — circulated across the state. Ajitha — the lone female in the group — was the lead character in most stories.

After the attack, the group entered the dense forests of Wayanad where they waited for their comrades from Thalassery. However, the police reached them first within a few days of the Pulpally incident.

From Naxal Ajitha to Anweshi Ajitha

The aftermath of the attack was brutal. Varghese was murdered in a fake encounter. Kisan Thomman died in a bomb blast. And Ajitha, 19 at the time, was paraded before crowds, tortured in custody, and sentenced to nine years in solitary confinement.

Anweshi’s short-stay home at Muzhikkal, Kozhikode, offers free shelter and support to abused women and children.

Yet, even within the walls of the Central Jail in Trivandrum and later the Cannanore (Kannur) prison, Ajitha’s search for justice never stopped.

Ajitha’s story begins amid the fire and fury of the Naxalite movement, but it does not end in the shadows of armed struggle.

Her transformation is one of Kerala’s most compelling narratives. She was a young revolutionary who walked through violence, isolation, and unspeakable torture, only to emerge years later as a relentless, firm voice for the voiceless, especially for women and children, whose sufferings were muffled behind closed doors.

It is easy to recall Ajitha, the daughter of Kunnikkal Narayanan and Mandakini, as the young woman who stormed the bastions of state power with a rifle. But to honour her legacy, one must remember her as ‘Anweshi’ Ajitha, the seeker who turned her pain into purpose and built Kerala’s oldest NGO for women and children that changed society’s perception of violence against women.

In 1993, Anweshi was born, not out of political ideology, but from the realities of thousands of women who had no space to tell their stories. From standing up for sex workers to fiercely investigating the death of Kunjeebi in police custody, to being a steady presence behind the triumphs of icons like Olympian PT Usha, Anweshi, and Ajitha, built a movement where survivors could be seen, heard, and believed.

Ajitha’s journey, from a prisoner to an anweshi (seeker) of justice, remains a legacy that cannot be contained in the frame of ex-Naxal.

Recounting her Naxalite days and the later transformation to South First, Ajitha said she was born in April 1950 into the revolution. Her parents, Narayanan and Mandakini, were committed communist workers.

The library at Anweshi.

Inspired by the Naxalite ideology, she dropped out of college while pursuing her pre-degree (equivalent to Plus Two) and joined the Naxalite movement, believing that study was a distraction from fighting injustice.

Disillusionment came with the 1967 Naxalbari uprising, when Marxist governments, both in West Bengal and Kerala, turned against farmers.

”It exposed how communists sacrificed ideals for power,” she said.

While spending time in jail after the 1968 attack, Ajitha studied the plight of sex workers. She was released in 1977, and by then, the movement had died. She chose a quiet life and married comrade Yakoob.

Now, for her, the association with the Naxalite movement is not a badge for recognition.

”Being an ex-Naxalite is not a qualification,” she said, stressing that her identity and strength lie in her commitment to women’s liberation, not her past affiliations.

Though she distanced herself from the movement years ago, Ajitha acknowledged that the experiences she gathered during that time laid a strong foundation for her later work in feminist activism.

However, she also recalled the deep gender inequalities that plagued the revolutionary space.

Marriage was initially forbidden for revolutionaries and viewed as a constraint on freedom. Falling in love with someone outside the ideological circle was treated with the same rigidity as in a feudal system, she recalled.

Her resistance to these gendered double standards within the movement became the starting point of her feminist consciousness.

The turning point came at the 1988 Women’s Conference, which inspired her to devote herself fully to the feminist cause.

At the time, Kerala’s women’s movement was still finding its feet. Ajitha went on to establish Bodhana, which rose to prominence through its protest against the murder of Kunjeebi, its involvement in dowry deaths, and the agitation to reopen the Mavoor factory.

Anweshi secretary P Sreeja spoke about the transformative influence of Ajiyechi (Ajitha) on the lives of countless women.

”For over 30 years, Anweshi has steadily earned the trust of the community by supporting women escaping abusive environments. Our experienced team, including leading psychotherapists and top legal minds from Kozhikode, acts as the first line of support for women navigating the complex journey out of abuse, helping them understand and access their legal rights,” she told South First.

She noted that Anweshi’s short-stay home at Muzhikkal in Kozhikode has become a sanctuary for many.

”The shelter offers safe, cost-free accommodation for women and children from Kozhikode and neighboring districts. It’s a place of healing, both physical and emotional, as they work to reclaim their lives,” she said.

Sreeja also emphasised the organisation’s wide-ranging efforts. From operating the Malabar region’s most extensive feminist library, to running awareness workshops for adolescents that promote gender equality.

”Whether it’s staging performances to spark dialogue, campaigning against violence, or using traditional outreach and new methods to challenge injustice, Anweshi continues to be a fierce advocate for women’s rights,” she added.

Unlike many other NGOs, Anweshi’s survivors often become its strongest pillars. Many women, who once sought refuge, return as volunteers, offering support to others who have treated similar painful paths.

”Meeting Ajiyechi was life-changing,” Aadima Pallikkara, a survivor who found a new life through Anweshi, told South First. “I came to Anweshi from the worst situation a woman could face. But my life turned around. Now, I support those who come here. Last month, we gathered for Women’s Day, and we have another gathering planned for next week. These moments give us incredible strength.”

Divvyaathmika, another survivor and now an active volunteer, shared a similar experience with South First.

”These days, we are extremely cautious about the complaints we receive. We verify each case before we take it up. When a suicide happens, we make it a point to visit, investigate, and ensure no life is silenced without justice. We also conduct regular sessions for adolescents, reaching wherever we can,” she said.

Anweshi first came into the national spotlight through its involvement in the infamous ‘ice cream parlour case’. But its mission has always extended far beyond headline-making cases.

Since 1995, Anweshi has focused on addressing domestic violence and empowering women caught in cycles of abuse and silence.

In the early years, abusers often dismissed the organisation, asking, “Who are you to question me for hitting my wife?” But Anweshi stood its ground, offering women not only a safe space but also the courage to say, “If you beat us, we will resist.”

Over time, this resistance helped shift public perception, what was once normalised as private family matters began to be recognised as serious legal and social issues. Today, even many men acknowledge that domestic violence is a crime, not a custom.

Speaking to South First, Sreeja said the organisation has intervened in tens of thousands of cases over the past three decades.

”There were days when we received six or more cases in a single day. More than 70% of the cases we handled found meaningful resolutions,” she said.

Sreeja also emphasised that Anweshi’s work, and that of similar women’s movements, was crucial in the formation of key legislation that protects women in India today.

”None of these laws came easily. Each of them is the result of years of struggle, pressure, and advocacy,” she said.

From the Domestic Violence Act of 2005 to the POCSO Act, the Criminal Law Amendment Act that followed the Nirbhaya case, and the POSH Act addressing workplace harassment, these landmark laws carry the imprint of women’s organisations like Anweshi that fought persistently to make the justice system more accessible and accountable for women.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).