Published Jan 12, 2026 | 8:00 AM ⚊ Updated Jan 12, 2026 | 8:00 AM

In a system where wrongful arrests often dissolve into silence, this case speaks loudly.

Synopsis: VK Thajudheen’s wrongful arrest in Kerala led to 77 days of imprisonment, torture, and public humiliation before the real culprit was found. The High Court awarded Thajudheen ₹14 lakh compensation, affirming violations of Article 21 and stressing constitutional accountability. His ordeal, documented in the book ‘The Stolen Necklace’, highlights systemic police failures and the enduring need for public law remedies.

”The first day in jail, I couldn’t even stand. I just went and sat in a corner.”

VK Thajudheen pauses before finishing the sentence. Celebration is still happening around him, after all, the Kerala High Court has finally acknowledged what he and his family lived through for years. But memory does not wait for verdicts.

For a man who had never stepped inside a police station, never seen the inside of a courtroom, and came home from Qatar only to conduct his daughter’s wedding, the journey from a white scooter on CCTV footage to a High Court judgment was brutal, humiliating, and irreversible in parts.

Recently, the Kerala HC awarded ₹14 lakh in compensation to Thajudheen and his family for a wrongful arrest, custodial torture, public humiliation, and prolonged incarceration — not merely as damages, but as a constitutional remedy under public law.

The court also left it open for the State to recover the amount from the erring police officers. It was not just a judgment. It was a warning.

Copy of judgment

On a July night in 2018, Thajudheen’s car was stopped near his home in Kadirur. What began as a routine interaction quickly turned ominous. Police officers insisted he step out, photographed him in the dead of night, and openly declared to his family, ”He is a thief.”

Within hours, Thajudheen was accused of a chain-snatching incident that had occurred six days earlier, kilometres away from where he lived. The police showed CCTV visuals of a bearded man on a white scooter and demanded a confession.

There was no recovery of gold, neither the scooter or verification of tower location data, nor serious attempt to rule out mistaken identity.

Instead, Thajudheen was stripped, tortured, and paraded through public roads, jewellery shops, and relatives homes- a public trial before any court could speak. His family watched as neighbours stared, whispered, and judged.

Except for his close family, everyone murmured, ”There’s no smoke without fire.”

He spent 54 days in judicial custody in Kerala. When he finally returned to Qatar, overstaying due to the case, he was jailed for another 23 days and lost his job.

77 days of imprisonment for a crime he never committed.

The real accused, a habitual offender was arrested only later, after his own wife revealed the truth to a police officer she trusted.

The writ petition – WP(C) No. 9494 of 2019 – was not just about money, but about dignity. Justice PM Manoj, in a detailed judgment held that the case involved a clear violation of Article 21, the right to life and personal liberty.

Drawing from landmark Supreme Court rulings such as Nilabati Behera, Rudul Sah, and Nambi Narayanan, the court reaffirmed a critical constitutional principle-

“When the State violates fundamental rights, compensation is not charity — it is a public law remedy.”

The bench made it clear that sovereign immunity has no place when police excesses trample constitutional guarantees. This compensation was awarded not as civil damages claim, but as constitutional accountability, leaving the door open for further civil and criminal proceedings.

Importantly, the court also stated that the government may recover the compensation from the officers involved — a quiet but powerful message to the police establishment.

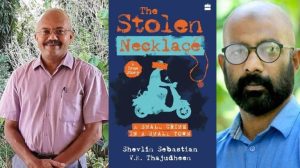

Shevlin Sebastian and VK Thajudheen

Senior journalist Shevlin Sebastian, whose book The Stolen Necklace played a key role in bringing national attention to the case, says the judgment validates something that numbers can never capture.

”People don’t understand the psychological toll” he told South First.

”His youngest child was humiliated in school. His career collapsed. His family was shattered. You cannot quantify that pain.”

The Stolen Necklace documented the human cost behind procedural abuse. The book was even submitted before the Court to underline that this was not a routine error — it was a systemic failure with human consequences.

Sebastian believes the judgment sends a message the police cannot ignore anymore-

”You cannot arrest on suspicion. You must be 110 percent sure before putting handcuffs on someone.” he said.

Advocate T Asaf Ali

Advocate T Asaf Ali, Thajudheen’s counsel and former Director General of Prosecutions, calls it one of the rarest of rare cases in Kerala jurisprudence, not because of the facts alone, but because of what the court chose to emphasise.

Speaking to South First he told that ”Most people, even police officers are unaware of public law remedies. This case has a larger perspective. It teaches that police misconduct does not end with suspension. There are constitutional consequences.”

Public law remedies, rooted in Articles 32 and 226 of the Constitution, allow courts to directly intervene when the State violates fundamental rights — through writs, declarations, injunctions, and crucially, compensation.

”This judgment should be a benchmark. It must be popularised. People must know that they have this right.” Ali says.

He also speaks of the pressure faced during the case – attempts at mediation, influence, even offers to settle.

”I did not bend. This judgment will be cited again and again.”

For Thajudheen, the verdict brought relief, not closure. ”They even offered lakhs to withdraw the case” he says quietly. ”But this was never about money. It was about the insult and injustice.”

Inside jail, he survived using the only skill he had — communication.

”There is a custom. New inmates get punished. I was terrified. I spoke to everyone, built rapport. That saved me.” he told South First.

Now, he plans to move civil court for further action. ”This is not the end. It’s only an interval.”

VK Thajudeen and family.

Ironically, his home is now visited by filmmakers, producers, storytellers — all wanting to adapt his ordeal for the screen. A cinema lover himself, Thajudheen says he is waiting, cautiously for the right creators. Because some stories are not meant for spectacle. They are meant for accountability.

In a system where wrongful arrests often dissolve into silence, this case speaks loudly-

A necklace can be stolen.

Dignity cannot be.

And when the State forgets, Constitution remembers.

(Edited by Amit Vasudev)