Published Mar 12, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Mar 12, 2025 | 9:00 AM

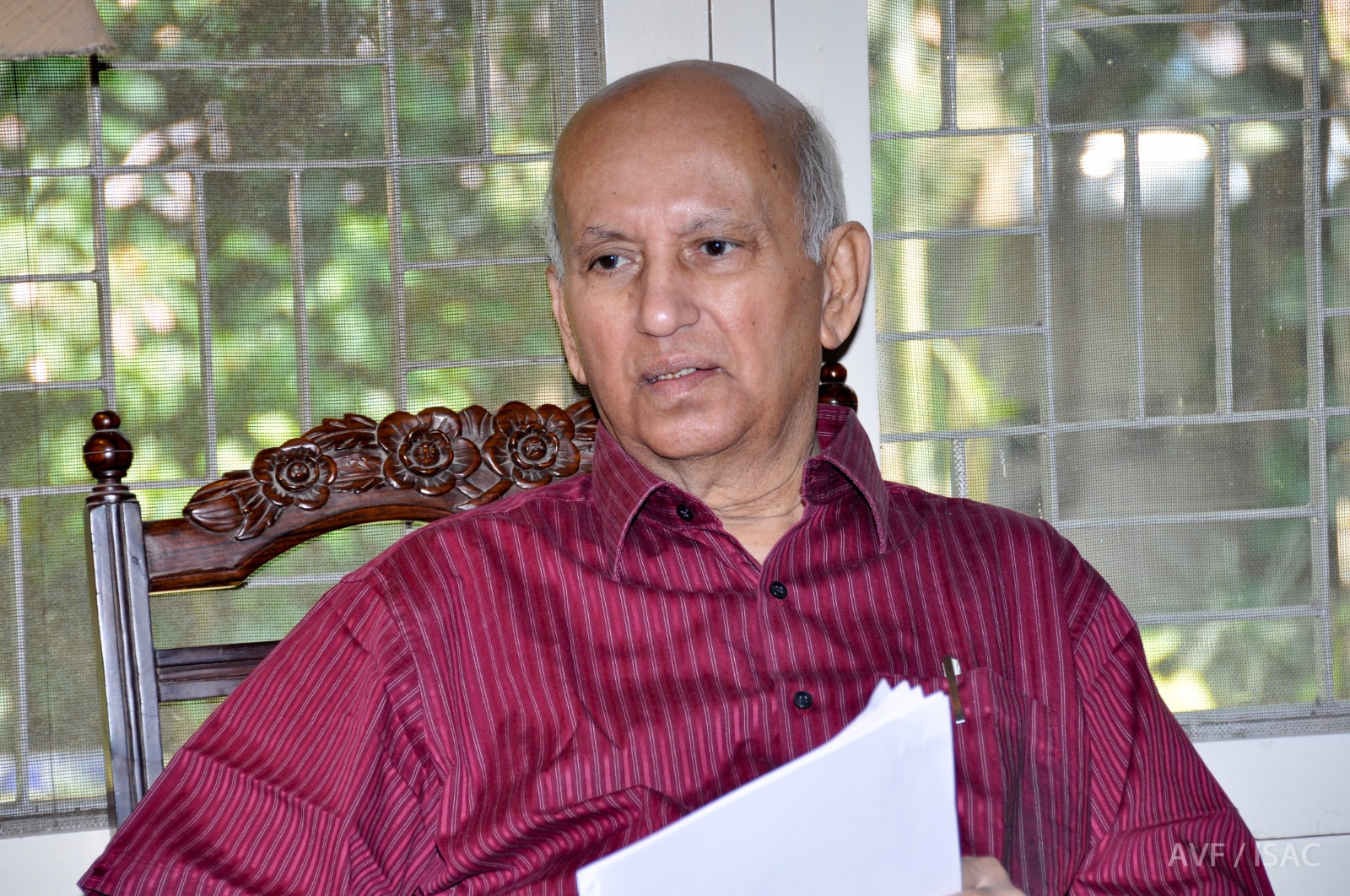

Former ISRO Chairman Prof. UR Rao (10 March 1932 – 24 July 2017).

Synopsis: The life of former ISRO chairman UR Rao is a textbook for the young generation, and generations to come.

A student who could not afford the university fee of ₹8 scaled great heights and defined the fundamentals and established the foundations of the Indian space programme.

He occupied the high echelons of the Indian space programme as chairman of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), and was the only Indian space scientist to be inducted into the Satellite Hall of Fame, Washington DC.

If UR Rao could succeed despite odds, there’s great hope for students and emerging scientists even in 2025 and the years beyond, when serious education has turned expensive and is out of reach of most ordinary Indians.

The story, experiences and life of Rao holds great import for today’s aspiring younger lot, not just in physics and science, but education in general.

His 93rd birth anniversary on 10 March is the right moment to recall and understand that no matter how hard-pressed one may be for money, if s/he is good, willing to work hard and grasp things right by getting to the right mentors and people, s/he can make it big.

Luck may play a part in the right people and circumstances helping the student to elevate her/himself.

Udupi Ramachandra Rao, not only did not have enough financial resources then (1930s through 1950s), he didn’t even have the backing of the most important people in anyone’s life — parental support.

His father, Lakshminarayana Acharya, did not earn much. Owing to his financial status, he did not want Rao to study beyond the 10th grade. Instead, he expected his son to start earning for the family.

Rao was his mother Krishnaveni Amma’s darling. However, she knew little about physics or science. There was no money and Rao received little backing for pursuing education beyond the 10th grade.

Rao had to make it on his own. Spurred by a burning desire to pursue education, he motivated himself from a young age. However, success did not always smile on him.

The student flunked his physics and other examinations in school. Yet, he kept pushing himself, and the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge opened its doors to the determined, brilliant student from Karnataka.

At MIT, Rao became a part of Italian-American experimental physicist Bruno Rossi’s group. Rossi was the student of the celebrated Italian physicist, Enrico Fermi, a Nobel laurate, who created the world’s first artificial nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1.

His childhood struggles might have molded Rao’s indomitable spirit. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) denying him a scholarship did not deter or discourage him. “If NASA won’t help me, I’ll do it myself,” was his resolve.

This resolve led him into setting a laboratory outside of Dallas to learn developing satellites and payloads.

Rao’s rebellious streak was visible throughout his career. He did not hesitate to set a deadline to India’s then unchallenged leader, Indira Gandhi, while building India’s first satellite.

“You tell me in an hour whether you’ll give me the money to build India’s first satellite. Else, I won’t be able to do it,” he reportedly told Gandhi.

Legend has it that the prime minister contacted Rao within the deadline to grant the money. On 15 April 1975, a Soviet Kosmos-3M rocket blasted off from Kapustin Yar in Astrakhan Oblast with Aryabhata, India’s first satellite.

Gandhi was not the only one who had a taste of Rao’s unexceptional and uncompromising negotiation skills. A 12-member Soviet team, too, had felt the heat before India joined the satellite club.

The Soviet team did not take Rao seriously when told that India was capable of building a satellite in a time-bound manner. They suggested Rao to develop and instrument, a payload, which they felt was enough for India.

Rao was blunt. “I’m here to talk about India’s first satellite, not just an instrument. Take it or leave it,” the Soviets had no alternative. They offered a free launch for the Indian satellite, and Rao grabbed the opportunity.

Former finance minister VP Singh and Finance Commission deputy chairman Dr Manmohan Singh — both later became prime ministers — too, had experience Rao’s blunt negotiation skills. “If you cut the money, I cut the space programme. If you give me the money, I’ll build the space programme,” he reportedly told them in uncompromising terms.

Born at Adamaru in Karnataka’s Udupi on 10 March 1932, Rao, went on to become one of the world’s best cosmic-ray scientist while working with Vikram Sarabhai. Rao has been considered to be the first space scientist to discover the continuous nature of the solar wind.

To this day, his research paper and findings are celebrated in the world of science and space.

Rao was also so exceptional that he oscillated between theory and practice with ease. This seamless movement from theory to application and application to theory reflected the man’s genius.

Who would have imagined that a failed student would one day have tea with Homi Jehangir Bhabha, the architect of India’s atomic programme, in Trieste, Italy, which has one of the world’s great science and physics institution?

Bhabha, who met Rao at Trieste, was heard asking another scientist: “Who is this man (Rao), so good at his thought?”

Rao eventually became the man who built and ran the space programme with Vikram Sarabhai, Satish Dhawan, K Kasturirangan, and others.

While these experiences are inspirational for today’s students, and young entrepreneurs setting up companies and trying on their own to make things work, Rao’s other legacy fundamentally set up India’s technological prowess and capabilities.

Rao was the man who not only built India’s first satellite, but also established India’s entire satellite system and constellation that helps the country monitor, assess and manage its natural resources, forestry, weather, agriculture, irrigation, floods, etc.

The satellite constellation he built has implications for the robust satellite system India has today. No wonder he is described as ‘the Satellite Man of India’.

Rao was the first Indian space scientist to grasp, understand, craft and build satellite technology (along with others like K Kasturirangan), something that he learnt while working on NASA’s Pioneer and Explorer Missions in the 1960s in the US. He was also inducted in the International Astronautics Federation (IAF).

Rao’s capabilities, experiences, self-made intellect and methods stand testimony to his academic rigour and the capability to translate and transform theory into application. Understanding how Rao did this gives aspiring youngsters a pathway, and hope to craft their careers at a time there is enough opportunities. Rao’s achievements came when there was nothing in hand, no money, no great expertise around, except a few dedicated committed and academically and intellectually sharp scientists.

Rao built India’s first satellite in sheds with tin roofs in Peenya, right in Bengaluru. There was no sophisticated building. And he built India’s first satellite locating the data reception centre in a lavatory because there was no space.

The great scientist was in a tearing hurry to get India’s satellites going that he told the then chief minister – ‘Don’t give me a space to build the satellite in Yelahanka. Every time I have to reach the place, I have to wait at the railway crossing for half an hour for the train to pass. I am not in the habit of wasting time. And I don’t have the time to waste while building our satellite.”

While Elon Musk is talking of efficiency, cost and time savings, productivity and results now, Rao had set the pace back in 1972.

Eventually, Rao built India’s first satellite in Peenya and brought the ISRO and space headquarters to Bengaluru, when it could have easily gone to Hyderabad or Thiruvananthapuram.

The Space Centre in Bengaluru now boasts of a sprawling campus, a vast network of research, space companies and entrepreneurship. It has also opened up vast educational and career opportunities and avenues, and intellectual options and excitement for the younger generation.

Rao’s birth anniversary is an inspirational day and moment for a whole new crop of emerging youngsters and students to learn and know that even in the face of hopelessness, the discerning would find light at the end of the tunnel.

Despite being a tough professional, Bhimsen Joshi’s khayals used to melt Rao, who would spent hours to listen to the maestro.

The episodes, experiences, and anecdotes in Rao’s life is legendary — the story of an ordinary man doing extraordinary things.

(P Ramanujam is a science, space, and technology commentator. Edited by Majnu Babu).