Published Apr 17, 2025 | 8:00 AM ⚊ Updated Apr 17, 2025 | 8:00 AM

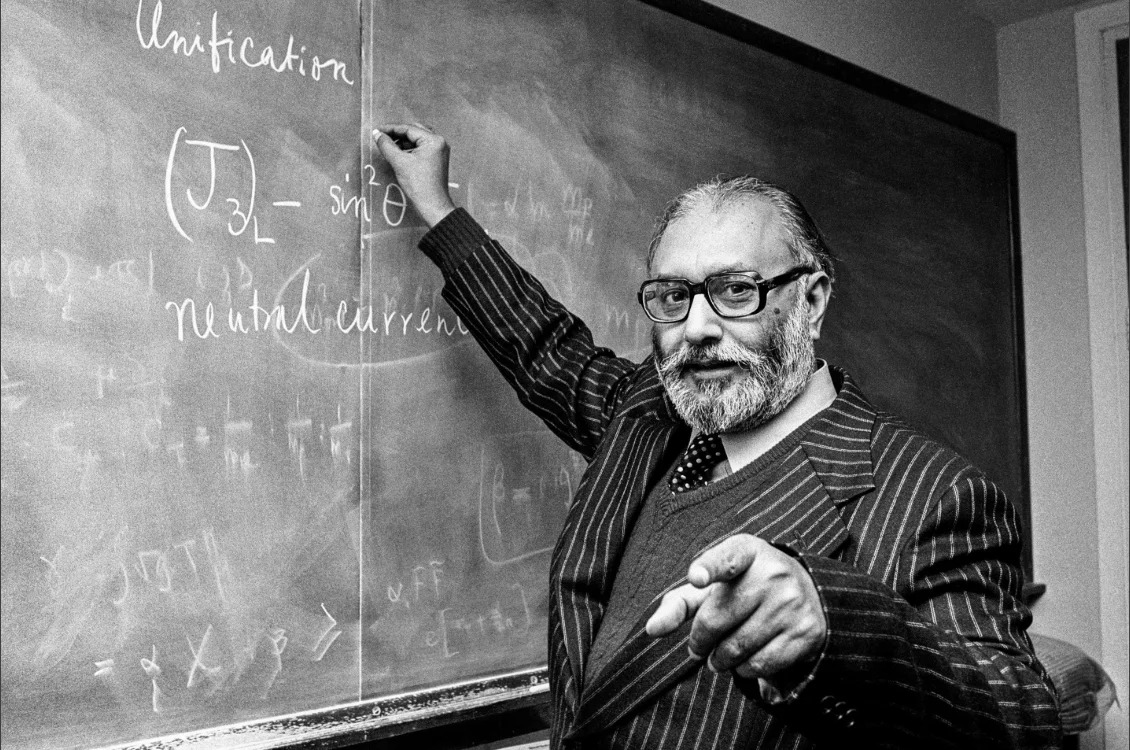

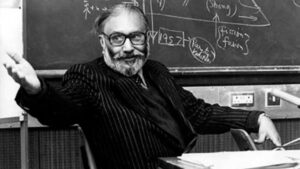

Pakistani theoretical physicist Mohammad Abdus Salam (29 January 1926 – 21 November 1996).

Synopsis: Mohammad Abdus Salam’s work on electroweak theory and symmetry, which won the Nobel, set a high standard for theoretical physics research. This work likely inspired Rao to pursue advanced studies in physics, contributing to the growth of physics research in India.

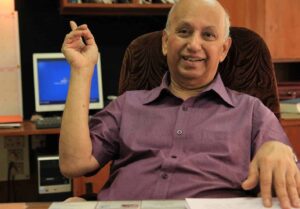

Several towering personalities had influenced legendary Indian space scientist UR Rao. They molded his outlook toward life, science, and the arts, which later reflected in everything he did.

Prominent among them were two greats, Homi Bhabha and Vikram Sarabhai. Others included the celebrated Richard Feynman, Arthur Clarke, Bruno Rossi, Enrico Fermi, and much earlier, JC Bose and Meghnad Saha.

However, there was yet another man, certainly known but a bit in the shadows of ‘Indian’ physics, science, and space. He had triggered Rao’s interest in physics after Prof RK Asundi produced the context for Rao’s early dive into the subject. He was the legendary Pakistani physicist and Nobel laureate, Abdus Salam.

Rao admired Salam’s vast repertoire, rigour and knowledge of physics. Salam acknowledged Rao’s worth and stature publicly. How did this connect come about between the two masters?

The Indian great himself had revealed about their first meeting.

“One great influence in science those days was Pakistani scientist Abdus Salam. A lecture by Abdus Salam was planned during my second year of M.Sc at the Banaras Hindu University. Abdus Salam at that time was not a Nobel Prize winner. He had just finished his Ph.d and did wonderful work and was a professor at Lahore,” Rao had said.

UR Rao.

“This was in January 1953, the year the Science Congress happened in Lucknow. Prof Salam came to the Congress for a talk. We were just amazed at the talk, it was fantastic. When I got to know him later, he would always tell me that he knew me well when I joined for my Ph.d under Dr. Vikram Sarabhai,” he said.

“Prime Ministers, Presidents, and Nobel laureates used to come to the Peenya sheds (in Bengaluru) to see us work on the first satellite (Aryabhata). Mrs Indira Gandhi came two to three months after August 1972. Mr Morarji Desai had come, and then later, even the Soviet Union physicist and Nobel laureate, Peter Kapitza. Peenya has seen so many people and so many Nobel laureates. Even the likes of Abdus Salam, S Chandrashekar, and Jean Parker, were there. A great number of other people came to see what we were doing and how we were going about our first satellite,” he recalled the days that led to India’s space age.

Salam had visited Peenya two to three times. It all seemed ordinary, but it wasn’t. Rao and India were doing something for the first time. And Salam, knowing well Rao’s worth, knew he was the right man to teach physics at Trieste in Italy.

Abdus Salam.

“Abdus Salam launched the International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) at The World Academy of Sciences, Trieste, Italy. He wanted me to initiate the first course. He said that he will not start the courses at the centre unless I direct, launch a course and give a talk. Therefore, I had to get several people together and teach a total course in two months, which I did,” Rao said.

“Physics was the core concern and I asked (K Kasturi) Rangan (former ISRO chairman) to join me and we had some people from Bangalore and people from outside. Prof Will Pritchard (space scientist) came from outside. I had to select the people, direct them, and make sure the course took off. This was on the invitation of Prof Abdus Salam. This was after the Aryabhata satellite launch in 1975. I took two months off for the programme,” he further said.

Rao then mentioned Salam’s address at the Lucknow Science Congress.

“It was a great speech by Dr Salam at the Science Congress in Lucknow, where our relationship began. I told Dr Salam, ‘We couldn’t understand half of what you said, but it was great.’ He would always ask, ‘Did I help you to do physics or did I dissuade you? Did he help me? He helped me. Not that we understood whatever he said, because quite several things he said were new,” the Indian scientist said.

Pakistani theoretical physicist Mohammad Abdus Salam shared the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics with Sheldon Glashow and Steven Weinberg for his contribution to the electroweak unification theory.

He was the first Pakistani and the first scientist from an Islamic country to receive a Nobel Prize and the second from an Islamic country to receive a Nobel after Anwar Sadat of Egypt.

Salam was the scientific advisor to Pakistan’s Ministry of Science and Technology from 1960 to 1974 and he laid the foundations for that country’s science, space and nuclear development.

His academic range was vast and complex. Salam made major contributions to quantum field theory and advancement of Mathematics at Imperial College London, neutron stars, black holes, quantum mechanics and mathematical and theoretical physics. He was also well-versed in Urdu and English literature in which he excelled.

During his doctoral studies, his mentors challenged him to solve within one year an intractable problem that had defied great minds such as Paul Dirac and Richard Feynman. Within six months, Salam cracked the renormalisation of the Meson Theory, which surprised scientists like Hans Bethe, J Robert Oppenheimer, and Dirac.

Salam also introduced the massive Higgs bosons to the theory of the Standard Model, where he later predicted the existence of proton decay.

Salam had also other strong Indian connections. He initially worked on Srinivasa Ramanujan’s problems in mathematics and later collaborated with Indian-American theoretical physicist Jogesh Pati.

Pati wrote to Salam several times expressing interest in working under the latter’s direction. Responding, Salam invited Pati to the ICTP seminar in Pakistan and together proposed the Pati-Salam model, a Grand Unified Theory.

When he won the Nobel, Salam took the medal to the house of his former professor, Anilendra Ganguly, who taught him at the Sanatan Dharma College in Lahore, and placed the medal around his neck.

“Anilendra Ganguly, this medal is a result of your teaching and love of mathematics that you instilled in me,” the proud student said.

Rao loved Bhabha and Sarabhai, and Salam knew exactly how worthy the two were when he visited Bombay (now Mumbai). Rao admired Richard Feynman, and Salam too solved a physics problem that Feynman had been grappling with.

Salam’s work on electroweak theory and symmetry, which won the Nobel, set a high standard for theoretical physics research. This work likely inspired Rao to pursue advanced studies in physics, contributing to the growth of physics research in India.

Salam’s establishment of ICTP in Trieste provided a platform for scientists from developing countries to collaborate and exchange knowledge with leading researchers worldwide. This initiative fostered a sense of international collaboration and broadened the horizons for scientists like Rao, promoting the development of science beyond the traditional centers.

Salam’s strong belief in promoting science and technology in developing countries, especially India, resonated with Rao, who shared his commitment to national development through science and technology.

Salam’s particular ability to break down barriers and play with interdisciplinary challenges inspired young scientists and set a high standard for Rao and other scientists in developing countries.

It is believed that Salam invoked the Gods while accepting the Nobel Prize. On the other hand, Rao was a shade perturbed by such invocation during any critical launch. He would eventually relent when the invocation came from others, but his focus was steadfast – get the job done, don’t waste time.

There’s this other thing. Salam is believed to have veered towards a nuclear edge in a perceived threat, while Rao worked consciously towards deterrence, even when he was in close quarters with the Manhattan Group, which built the world’s first atom bomb.

Salam’s legacy, while undoubtedly valuable and rare in world physics, now remains neglected in his country. Rao’s legacy has certainly been celebrated.

Salam’s legacy is once again coming back to Bengaluru, in the form of a play, The Trial of Abdus Salam, by playwright Nilanjan Chaudhury.

The play in the subgenre, ‘science theatre’ as Chaudhury puts it, depicts the collision of ideas of physics with human drama, and conflicted scientists emerge as charismatic protagonists.

The Trail of Abdus Salam will stage at Ranga Shankara on Friday, 18 April.

(P Ramanujam is a science, space, and technology commentator. Edited by Majnu Babu).