Radha ajji never dreamed she would learn to read Kannada, let alone translate DVG’s 'Mankuthimmana Kagga' into Tamil. But destiny had other ideas. Here is the story of how Radha ajji learnt to read and write Kannada in her late 60s and went on to create 945 verse translations in Tamil of one of 20th-century Kannada literature’s greatest and most-loved works.

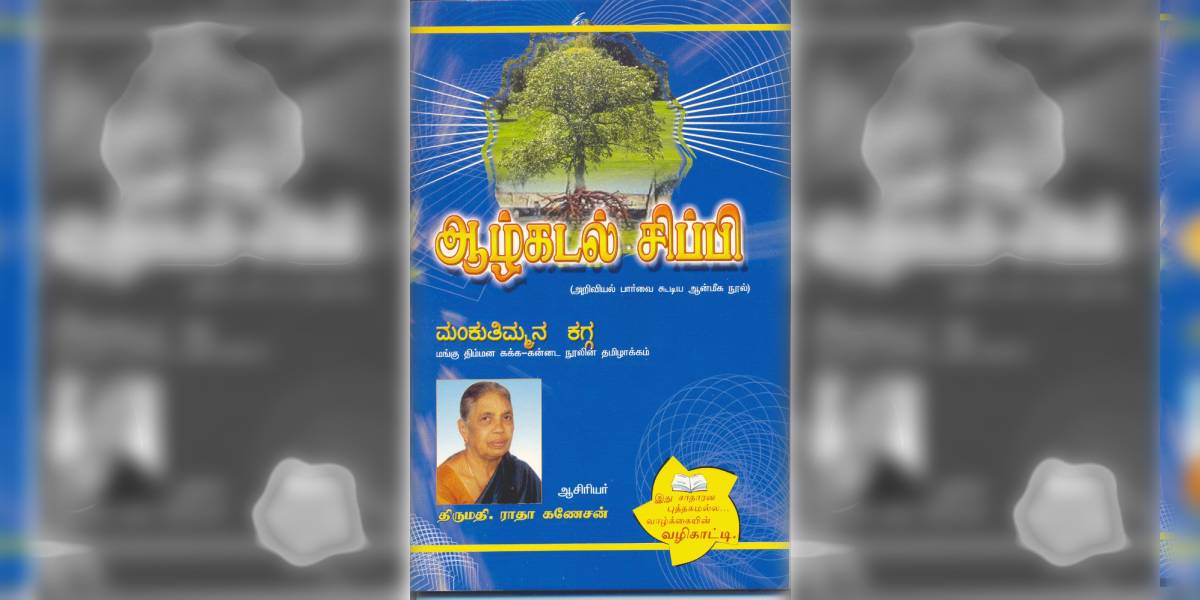

Cover page of ஆழ்கடல் சிப்பி or Aazhkaḍal Chippi (A G Ramakrishnan)

உறுதியோ இல்லை, வேண்டுவதே கிடைக்கும் என்று

அறிவும் இல்லை, வேண்டுவது என்னவென்று

இறுதி தீர்ப்பில் விருப்பம் அவனுடையதே என்னும்

உறுதி மனம் கொண்டு உள்ளபடி ஏற்றிடு – மங்குதிம்ம (Verse 943)

ಬೇಡಿದುದನೀವನೀಶ್ವರನೆಂಬ ನಚ್ಚಿಲ್ಲ

ಬೇಡಲೊಳಿತಾವುದೆಂಬುದರರಿವುಮಿಲ್ಲ

ಕೂಡಿಬಂದುದನೆ ನೀನ್ ಅವನಿಚ್ಛೆಯೆಂದು ಕೊಳೆ

ನೀಡುಗೆದೆಗಟ್ಟಿಯನು – ಮಂಕುತಿಮ್ಮ

There is no guarantee that the Supreme

will grant you whatever you ask for

You don’t know what’s the right thing to ask!

Whatever you obtain, assume that is divine will

and make your heart strong [1]

Like most disciplined old people, Radha ajji is waiting for me. She is wearing a faded-brown saree and a small, bright-coloured yellow bindi. Seated at a table in a room just off the hall, some handwritten sheets of paper and a copy of her book lie spread in front of her.

I greet ajji and sit down in the chair opposite hers. I ask if I can take a closer look at the book. It is a blue book, slimmer than its Kannada counterpart. Tamil letters I can’t fully recognise adorn the cover.

Near the bottom of the cover is a picture of Radha ajji looking quite a lot younger and, I daresay, rather different. The difference will make sense to me when I learn the book was published more than 15 years ago.

The book is the reason I have come to see her. It is a Tamil verse translation by Radha ajji of DV Gundappa’s famous Kannada work, ಮಂಕುತಿಮ್ಮನ ಕಗ್ಗ (Mankuthimmana Kagga), a collection of 945 quatrains (four-line verses) that deal with the multifariousness of life. The work is often called Kannada literature’s Bhagavad Gita.

Though I have known Radha Ajji for some ten years or so now — two of her grandsons are good friends of mine and I am well acquainted with two other grandsons — I have never had much opportunity to talk to her. Our interaction on the few occasions I have visited my friends’ house has naturally been limited.

Letter sent by APJ Abdul Kalam to Radha ajji after reading ஆழ்கடல் சிப்பி or Aazhkaḍal Chippi ( G Ramakrishnan)

Nonetheless, it was during one of those visits that I first learnt about the book. Telling me about the translation, her grandson and my classmate Vyass had said, “She even gave a copy of the book to Abdul Kalam.”

Though I had not myself read the Kagga at the time, I had heard about it and was naturally impressed by ajji’s effort. My friend’s words also intimated to me that Radha ajji could speak Kannada; since then, ajji and I have mostly talked in Kannada when we’ve met.

In her late 80s now, Radha ajji is no longer as active as she used to be just a few years ago. By active, I am referring to physical activity (though that too has not ceased); mentally, she is more alert than a lot of people younger than her.

“I go to sleep at 8 and wake up at 3.30,” she says, somewhat proudly. I am reminded of my own maternal grandmother, Indira ajji, who woke up at 3.30 or 4 in the morning for as long as I knew her and whose energy was such that she kept house until she was 81 — when a serious illness finally forced her to slow down.

I put my phone’s recorder on and Radha ajji and I spend the next hour or so talking, mostly in Kannada. (Incidentally, I notice that ajji’s Kannada is obviously rusty, likely on account of the limited opportunities she gets to speak it.)

We discuss her introduction to DVG’s Mankutimmana Kagga, the challenge of learning to read a new language at an advanced age, and why and how the translation happened.

What follows is a mix of what I recorded and my own recollection of that afternoon.

Like so many works of literature, Radha ajji’s was catalysed by a personal tragedy.

Speaking about it, ajji says: “After my husband retired, we decided to move to Bangalore. My eldest son, Ramakrishnan, had joined the BPL company in Bengaluru and we decided to go with him. We arrived in Bangalore on 10 May 1989. My second son, Ananthasubramaniam, had done his CA and he too got a job and moved to Bangalore.”

“Some years later, my third son, Giridharan, also came down from Bombay and all of us moved in together in a place in Girinagar. A few years later, we built our own house in Hanumanthanagar and moved there.” Radha ajji’s voice has been calm so far but it now starts to crack.

“Everything was going well, but on 17 June 2003, the calamity happened and I lost my husband and my son.” Ajji’s voice cracks further and her eyes fill with tears.

“I was with them in the car at the time, but I survived. The retina of my left eye was damaged but I lived. But I have no idea why that devaru (god) chose to spare only me and to take away my husband and my beloved son.” Ajji’s voice is a wail now and it is clear the passage of 20 years has not fully healed the deep wound left by the tragedy.

I cannot think of anything to say, so I lean across the table and pat ajji’s hand as she recovers her poise. As I do so, I notice her left eye looks glassy green, as if a film has been laid over it.

But the hard part is over. For the rest of our conversation, ajji’s poise does not falter.

I remind ajji of what she once told me about her husband saying she should learn Kannada because that was the language of the land they’d moved to. She laughs and says yes, then says he said the same thing to their daughters-in-law.

When I ask if her husband himself learnt Kannada, she says, “he never learnt it”, chuckling in merriment as she answers.

I join her in laughing and then ask her how and when she came to learn Kannada and about DVG and his Kagga.

“I first learnt about the Kagga when my son Ramakrishnan’s IIT classmate, Chidananda, who was with the Chinmaya Mission, gave me a copy in 1998. He told me it was a very famous book in Kannada and said I should read it.”

“I tried reading it at the time but the English translation wasn’t attractive and didn’t seem to give the proper meaning, so I gave it up. A little later, I went to someone who knew Kannada to learn the meaning from them, but that attempt too stopped soon.”

Curious, I ask ajji why it was DVG’s Kagga — instead of, say, the Bhagavad Gita or the Tirukkural — that she turned to for solace during that time in 2003.

She says, somewhat wryly, that it was an “accident”, much like the accident that left her bereaved. But she is also being serious – it had never occurred to her that she would read the Kagga in Kannada, let alone translate it into Tamil.

“I really needed something to distract me and take me out of myself after the calamity,” says ajji. “This book by DVG happened to be lying around. I picked it up about four-five months after the accident and began to try to read it in Kannada.”

“And you hadn’t ever tried reading Kannada until then?” I ask. As someone who didn’t formally study Kannada in school and learnt it in my early 20s, I know how hard it can be to pick up a new script.

“I had picked up bits and pieces by looking at signboards, but that was all,” says ajji.

The translation project turned out to be the tonic Radha ajji needed. She began by haltingly reading the Kagga in Kannada, an experience she did not find satisfying.

“When something is in our mother language, that’s when it becomes easy, doesn’t it?” says ajji as she speaks about translating the opening verse of the Kagga.

This first step led to the next and soon enough, Ajji was deeply caught up in the Tamil translation of DVG’s Kagga. “Some nights, I used to stay up until 2 am, trying to find the most satisfactory way to translate a certain word or line,” says ajji.

We will not go into the details of Radha ajji’s project, but it is not difficult to see that she threw herself into the work with a fervour born of tremendous suffering and sadness.

“I translated about 10 verses from the Kagga into Tamil and my eldest son, Ramakrishnan, told me they had come out well and encouraged me to continue. So I did. I thought I would perhaps do 400 or 450 but I never expected to translate all 945 of them.”

But translate them all she did, completing the translation sometime in 2006. But, says ajji, she never considered publishing her work and credit for that must go to entirely to her son, AG Ramakrishnan, former chairman and currently professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc).

“He went to a Tamil medium school and his Tamil is good, so he proofread the entire text and then found a publisher for it in Chennai,” says ajji. The book was eventually published in 2007 by ‘Printfaast’.

So did the whole process of reading the Kagga and translating it help you, I ask ajji. Did it make things better?

Yes, she says, it did help. “It definitely brought me nemmadi (comfort), especially because I had to read each quatrain several times in the course of translating it into verse.”

DVG was a great man, she adds. “The Kagga is the equal of the Bhagavad Gita.”

Cover page of ஆலய வலம் (Aalaya Valam: Around The Temple), Radha ajji’s Tamil book on some lesser-known temples of Karnataka (AG Ramakrishan)

Radha ajji’s translation of the Kagga is titled “ஆழ்கடல் சிப்பி (Aazhkaḍal Chippi), which translates to “Deep-sea Pearls”. Ajji says she named it that because the poems of the Kagga are valuable pearls, which can be obtained only through concerted effort and enterprise.

Interestingly, “Deep-sea Pearls” would catch the attention of the ‘Tamil Sangam’ of Bengaluru.

“My son, Ramakrishnan, gave them a couple of copies for their library. Some time later, the president of the Sangam himself came home, completely unexpectedly,” says ajji.

“He congratulated me on my effort and marvelled that I had translated a work of such magnitude into Tamil. He then said the Sangam wanted to arrange an event to formally felicitate me.”

At the function, Ajji was gifted the customary shawl and basket of fruits. She was then conferred the title, ‘அயர்ந்திடா அன்னை’ (Ayarndiḍaazh Annai), a phrase that translates to “untiring mother”.

Radha ajji has certainly lived up to this title. In addition to all her other duties, including those as a mother and grandmother, Radha ajji has, since the publication of “Deep-sea Pearls” in 2007, written 12 more books, including her autobiography in Tamil titled “வாழ்வின் ஜோதி (Vaazhvin Jyoti: The Light of Life)”.

Some of her other books are a Tamil translation of Anupama Niranjana’s popular Kannada book, “ದಿನಕ್ಕೊಂದು ಕಥೆ (Dinakkondu Kathe: A Story a Day)” and a book in Tamil, “ஆலய வலம் (Aalaya Valam: Around The Temple)”, on the lesser-known temples of Karnataka.

When I enquire about her autobiography, she says the title is a play on words, Jyoti being the “home name” of her deceased son, Ananthasubramaniam. (The word “Jyoti” is a Sanskrit word meaning light.) “Most of the book is devoted to Jyoti,” says Ajji. “He really was the light of my life.”

As our conversation winds down, I ask ajji if she can tell me which poems from the Kagga she likes best. I tell her she can choose verses she particularly liked or whose Tamil translations she is especially proud of.

Per my request, Ajji marks a few verses for me in her copy of the book and gives it to me. (The verse that opens this essay is among them.) I put it into my strap-on bag, seek ajji’s blessings, and take my leave.

As the auto speeds away, I think about what I’ve heard and marvel again at ajji’s remarkable courage and determination.

It seems fitting to end with some of the verses and translations from the Kagga that ajji marked in the book. The Tamil translation comes first; it is followed by the Kannada original and an English translation.

வாழ்வின் பொருளென்ன? உலகின் பொருளென்ன?

வாழ்வு உலகிடை உள்ள உறவென்ன?

காணுதற்கரிய பொருளேதும் உண்டாயின் அதுவென்ன?

உண்னம ருசுவென்ன அதற்கு? – மங்குதிம்ம (Verse 4)

ಏನು ಜೀವನದರ್ಥ? ಏನು ಪ್ರಪಂಚಾರ್ಥ?

ಏನು ಜೀವಪ್ರಪಂಚಗಳ ಸಂಬಂಧ?

ಕಾಣದಿಲ್ಲಿರ್ಪುದೇನಾನುಮುಂಟೆ? ಅದೇನು?

ಜ್ಞಾನ ಪ್ರಮಾಣವೇಂ? — ಮಂಕುತಿಮ್ಮ

What is the meaning of life?

What is the meaning of the world?

What connects the beings and the world?

Is there anything we can’t see here? What is it?

Can knowledge help perceive it?

எது வரை உயிருளதோ அது வரை வாழ்வு உண்மை

எடுத்து விளக்கும் பொறுப்பு எம்மைச் சார்ந்ததல்ல

எல்லை வரை சென்று ஊக்கம் கொண்டு முயல்வதே

எடுத்த பிறவிக்குப் பயன் – மங்குதிம்ம (Verse 398)

ಇರುವನ್ನಮೀ ಬಾಳು ದಿಟವದರ ವಿವರಣೆಯ

ಹೊರೆ ನಮ್ಮ ಮೇಲಿಲ್ಲ ನಾದವರ ಸಿರಿಯ

ಪಿರಿದಾಗಿಸಲು ನಿಂತು ಯುಕ್ತಿಯಿಂ ದುಡಿಯುವುದೆ

ಪುರುಷಾರ್ಥಸಾಧನೆಯೊ – ಮಂಕುತಿಮ್ಮ

It’s true that this life exists as long as we’re alive

We aren’t responsible for its details

Toiling skilfully to enhance its wealth

is the achievement of the life’s purpose

குஸ்தி பந்தயத்தில் வெல்ல இயலா மல்யுத்த வீரன்

கஷ்டப்பட்டு கற்ற பிடிப்புகள், அசைவுகள் வீணாயினவா?

முஷ்டியின் திண்னம அவன் உடற்கட்டில் காணவரும்

புஷ்டியான லலிமை குஸ்தி பயன் – மஞ்குதிம்ம (Verse 588)

ಜಟ್ಟಿ ಕಾಳಗದಿ ಗೆಲ್ಲದೊಡೆ ಗರಡಿಯ ಸಾಮು

ಪಟ್ಟುವರಸೆಗಳೆಲ್ಲ ವಿಫಲವೆನ್ನುವೆಯೇಂ?

ಮುಟ್ಟಿ ನೋಡವನ ಮೈಕಟ್ಟು ಕಬ್ಬಿಣ ಗಟ್ಟಿ

ಗಟ್ಟಿತನ ಗರಡಿ ಫಲ – ಮಂಕುತಿಮ್ಮ

If a wrestler does not win a fight

will you say his training of

grips, holds, and punches is a waste?

Touch to feel his body; it’s strong like iron

Strength is a result of training

புன்னகை மலரட்டும் முகத்தில், காதுக்கு எட்டுவது வேண்டாம்

மென்மை இருக்கட்டும் சொல்லில், தருமத்துக்கு குறைவு வேண்டாம்

மீதமிருக்கட்டும் மன உணர்ச்சிகள், இன்ப நுகர்ச்சிகளில்

மிகை வேண்டாம் எவ்விடத்தும் – மங்குதிம்ம (Verse 724)

ಸ್ಮಿತವಿರಲಿ ವದನದಲಿ, ಕಿವಿಗೆ ಕೇಳಿಸದಿರಲಿ

ಹಿತವಿರಲಿ ವಚನದಲಿ, ಋತವ ಬಿಡದಿರಲಿ

ಮಿತವಿರಲಿ ಮನಸಿನುದ್ವೇಗದಲಿ, ಭೋಗದಲಿ

ಅತಿ ಬೇಡವೆಲ್ಲಿಯುಂ – ಮಂಕುತಿಮ್ಮ

Have a smile on your face,

but let it not be heard by the ear

Speak with gentleness

but don’t hide the truth

Let there be a limit for

mental agitation, physical indulgence

Avoid excesses everywhere, always

கவிஞனுமல்ல கலைஞனுமல்ல நானொரு வானம்பாடி

கவிதை புனைந்துள்ளேன் சிற்றறிவுக்கு எட்டியபடி

கட்டியுள்ளேன் பாட்டிதனை பாமர மொழியின்படி

கவனம் வைக்க எளிது படி – மங்குதிம்ம (Verse 938)

ಕವಿಯಲ್ಲ, ವಿಜ್ಞಾನಿಯಲ್ಲ, ಬರಿ ತಾರಾಡಿ

ಅವನರಿವಿಗೆಟುಕುವವೊಲೊಂದಾತ್ಮನಯವ

ಹವಣಿಸಿದನಿದನು ಪಾಮರಜನದ ಮಾತಿನಲಿ

ಕವನ ನೆನಪಿಗೆ ಸುಲಭ – ಮಂಕುತಿಮ್ಮ

Not a poet, nor a scientist, a mere wanderer

The wisdom and nuances of the Self

that was within his reach,

he arranged in simple words, for all

Poetry is easy to remember

(Those readers who would like to contact Radha ajji or get a copy of her book(s) can write to agrkrish@gmail.com)

[1] All the English translations presented here are from the book, “Foggy Fool’s Farrago”, authored by Malathi Rangaswamy and Hari Ravikumar and published by W.I.S.E Words Inc.

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 25, 2024

Jul 25, 2024

Jul 25, 2024

Jul 24, 2024