A branch of study that could find a solution to Alzheimer’s, brain mapping can also aid the police in cracking crime.

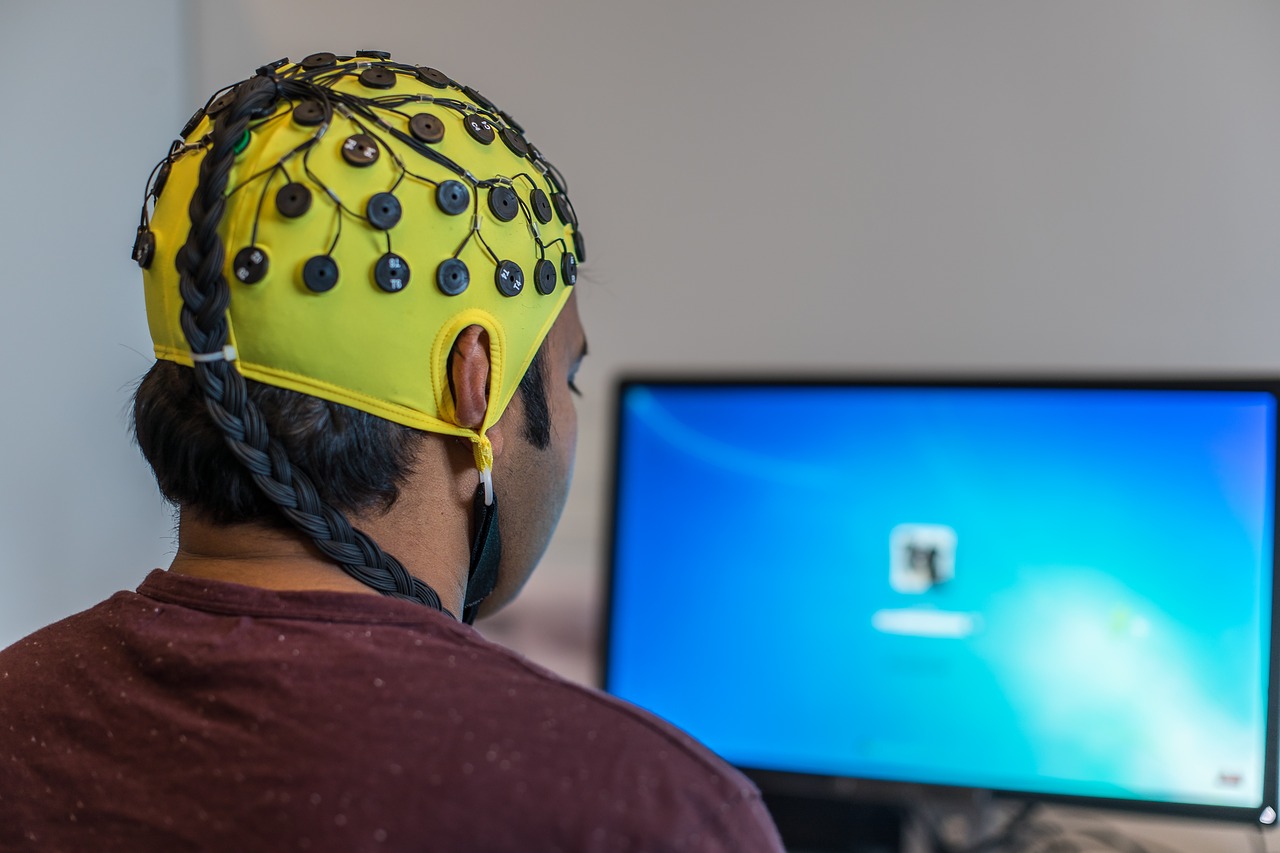

A brain mapping or EEG test being conducted. (Representational image/Creative Commons)

Brain Electrical Oscillation Signature Profiling (BEOS). That is the latest technology that Karnataka Police is pushing for scientific crime detection.

Armed with a recently-acquired device for “brain fingerprint” technology, Karnataka’s ADGP( Crime and Technical Services) R Hitendra, in a recent circular to all police stations in the state, has asked all investigating officers to make use of new advanced tech.

BEOS, or the “brain mapping test”, as the circular addresses it, uses ElectroEncephalography (EEG), which studies the “electrical behaviour” of the human brain.

This behaviour can even be in response to a person’s experience of, knowledge of, or involvement in, an incidence of crime, the circular said.

The circular also sought to clear any misgivings over the use of BEOS/brain mapping in police work, saying it did not violate a person’s fundamental or constitutional rights, and was non-invasive as it did not require injection of chemicals or drugs into individuals, or cause any harm to them.

Interestingly, the BEOS methodology is credited to Prof CR Mukund, a neuroscientist and former head of clinical psychology at the Bengaluru-based National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS).

But what exactly is brain mapping, and how does it fit in with police work?

A complex organ, the human brain has billions of cells, also known as neurons, which receive messages — electrical impulses — from all over the body.

These impulses create what are called “brain waves”, or what the Karnataka Police described as the brain’s “electrical behaviour”.

Neuroscientists are now trying to decode these brain waves, that is, trying to figure out how the cells “speak to each other” through the electrical impulses. For this, they needed a “map” of cell networks, as it is this network in the brain that drives the way we think and behave.

Basically a test, brain mapping involves the creation of this visual map by measuring the electrical activity in the brain, just as an electrocardiogram, or EKG, measures the heart’s electrical activity.

Brain mapping is also another term for EEG, the neuroscience technique the Karnataka Police circular talked of, though success with understanding the brain has been only partial so far.

The test to measure the body’s most complex organ is actually a simple process. If you are the subject, a cap with small holes in it will be put on your head — after your forehead and earlobes are cleansed of any oil.

A cooling gel will then be put into the holes in the cap, which will be connected to the EEG equipment through a set of wires.

At this point, your brain waves become visible on a computer screen. The brain mapping test that follows consists of two parts: The recording of brainwaves, and drawing up the brain map.

• Brainwave recording: You will be required to sit still, minimising all movement, and brainwaves recorded with your eyes open and closed. The process usually takes about 10 to 20 minutes.

• Brain map creation: The recorded brainwaves are analysed using complex mathematical algorithms. The data is then converted into a multi-coloured brain map.

The brain map report contains data that indicates conditions such as anxiety, depression, epilepsy, head injuries, brain tumours, or even behavioural issues.

That apart, it analyses brainwave activity, where green indicates normal, red shows elevated levels, and yellow means extreme levels.

The display shows different types of waves.

• Delta waves help rejuvenate the mind and body when one sleeps or relaxes;

• Theta waves help with processing information, making memories, feel, and daydream, and are strongest when one focusses internally, meditates, or prays;

• Alpha waves help with staying alert;

• Beta waves help with logical thinking and concentration;

• Gamma waves help process information and solve problems.

The amount of various waves in different parts of the lobe impacts behaviour. For instance, low beta and gamma waves in the frontal lobe point to weak impulse-control and uneasy social relationships.

Similarly, overactive beta and gamma waves in the parietal lobe indicates impulsiveness, and excessive delta and theta waves in the occipital lobe indicates memory problems.

Of course, research into brain mapping stems from a need to crack the causes of brain disorders and develop therapies for diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

However, neuroscience techniques are now being used in police work too, with forensic experts applying them to decipher whether a person’s brain recognises elements from a crime scene or not.

The reasoning: An involved person’s brain will recognise such elements; an innocent person’s will not.

This played out at Bengaluru’s Forensic Science Laboratory during the brain mapping test of an accused in the murder of a Canadian, Aasha Goel, found dead in Mumbai on 23 August, 2003.

When the accused was shown a photograph of him wearing an orange shirt, his brain wave impulses became turbulent. Following this, the Bengaluru police alerted their Mumbai counterparts.

On searching the house of the accused, the Mumbai police found the orange shirt, which had blood stains. DNA tests showed it belonged to the victim. The success in the Aasha Goel case has only made the test more reliable for investigating authorities.

The Supreme Court has ruled that the use of neuroscientific investigative techniques, including brain mapping, violated an accused person’s Constitutional rights.

In the 2010 Selvi versus the State of Karnataka case, it ruled that such techniques constituted testimonial compulsion: Forcing the accused to give testimony, such as handwriting sample and thumb impression while in custody.

As such, these techniques violated a person’s right against self-incrimination under Article 20(3) of the Constitution, which says “no person accused of any offence shall be compelled to be a witness against himself”.

The court also found them to violate Article 21, according to which, “no person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law”.

What this means is that EEG reports of suspects/accused are not admissible in the court of law.

However, sources in Bengaluru’s Forensic Lab said, brain mapping — organised with the consent of the accused — could yield leads, as in the Aasha Goel case, which the police can pursue later.

Jul 27, 2024

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 26, 2024