Published Jan 16, 2025 | 2:39 PM ⚊ Updated Jan 18, 2025 | 3:00 PM

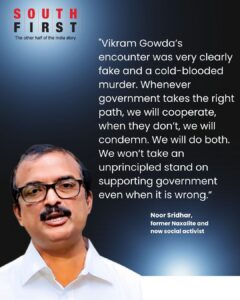

Noor Sridhar and Sirimane Nagaraj, former Naxalites and now social activists.

The Karnataka government declared itself a ‘No Naxal State’ on 8 January after six Left-wing extremists, engaged in armed struggle, surrendered.

The event was marked with fanfare after Chief Minister Siddarmaiah handed a copy of the Indian Constitution to the former Naxals, much to the BJP’s chagrin. BJP leaders accused the ruling Congress of according red-carpet welcome to violent Naxals.

Over ten years ago, two former Naxals, Noor Sridhar and Sirimane Nagaraj, gave up armed struggle and joined the societal mainstream. Now, they are renowned social activists.

In an interview with South First, they spoke about what it meant to take up and give up arms, their journey from Naxalism to democratic activism, their commitment to ideology and the need to seek accountability from those in power.

Q. You have said that the surrender of armed members means only 40 percent of the work is done. What do you mean by that?

Noor Sridhar: I say 60 percent of the work is pending because this entire process was undertaken as ‘Mission Democratic Mainstream’. Our intention was not to make these comrades surrender and put them in jail but to bring them to the democratic mainstream.

What has happened in Karnataka is unique. Its uniqueness stems from the fact that traditionally there were two models — one, to curb and crush the movement through encounters, suppressions, oppression and arrests; another is surrender.

This is neither. Surrenders take place in states like Chhattisgarh and Telangana also but they are humiliating. Naxals surrender, confess to their crimes and spend a lot of time in jail. Even when they get out of jail, finding a livelihood becomes difficult and social activism ends.

This is not like that. Our model is an attempt to bring them to the democratic mainstream from armed struggle. When we surrendered too, we put forth only one condition — there should be no restrictions for us to continue with our struggle through democratic means. If that hadn’t been accepted, we would not have returned either.

Karnataka government accepted our condition and hence we returned to the mainstream. Even now, this negotiation is fructified on two key points.

First, they will be treated in a dignified manner and not like criminals. Second, they won’t be left to rot in jail and will be given an opportunity to live in society and pursue social activism.

So far, we have only been able to bring them from the forests to jail but this process was dignified or even in a glorified manner. It will encourage others who want to change their path.

Ultimately, they transitioned from the jungle to prison but now they need to make a comeback from prison to society.

It is a challenge for Karnataka because there are cases against them in Kerala also. There are dozens of cases with serious charges including the Arms Act and UAPA [Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act]. It is not easy to relieve them from all these cases. It is a big challenge.

Q. It has been more than a decade since you gave up arms. How have the 10 years been for you? What should those who have surrendered expect?

Sirimane Nagaraj: Noor Sridhar and I gave up arms together. We intended to come to mainstream society and continue our fight and activism through democratic processes for pro-people struggles.

That has been fulfilled completely. Initially, there were some police officers who had the hangover of suspicion and thought we would go back to armed resistance, re-group etc. A couple of years later that changed.

Today, even police officers give us due respect. We take part in several campaigns and struggles in civil society. Our intent has been fulfilled and the government hasn’t troubled us. The six comrades who have returned now have also come with the same intent. The government has to fulfil that and resolve the problems that may crop up.

Q: What was your life like before 2014 and what is it like now?

Noor Sridhar: My lifetime can be divided into three periods. Till 2006, 2006 to 2014 and post-2014. In 2006 we moved away from the old Maoist movement. We disassociated from the party. We wanted to start an open and democratic movement but it was a tough period.

There were cases against us, we were being hunted, our ‘Wanted’ posters were put up and on the other hand, we had moved away from the party which means there were no financial resources. All the mass movements we had built collapsed at the time. From scratch, without support, with a lot of risk, we had to build it. 2006 to 2014 was a very tough period of my life.

We were underground with limited resources and were trying to build a democratic movement. We had started preparations then in 2006 to 2008 for democratic struggles. From 2008 we were building teams in different places openly to take up democratic means of resistance. We were underground but team members were taking up mass movements democratically. It was a tough journey. When the BJP lost and Congress came to power in 2013, civil society played a big role and negotiated our return. The government agreed to our terms and conditions.

In 2014 we came to democratic mainstream and in 2015 we got out of jail. From then on our lives drastically changed. When we came out, there was a fanfare. We turned up overground in Chikkamagalur. The cream of Karnataka’s civil society was there.

Leaders of all movements, literary icons — the democratic core, conscience keepers of the society welcomed us. We told them we won’t surrender before the police. Freedom fighter and Gandhian HS Doreswamy was there. Several ideological streams — Gandhians, Ambedkarites, Marxists, Lohiaites, and Feminists received us.

After coming back, we toured the whole state continuously. We were welcomed everywhere. There were discussions on what is the solution to the problems in society and how to move forward. It was clear that everywhere people wanted a change — a committed leadership. Not an isolated path like an arms struggle, but an effective democratic movement. They expected that from us.

They asked one question wherever we went — “What is the solution for the problems in the society? Bullet or Ballot?” It was the same question everywhere — “Bullet or ballot”? Our response was — “in these times neither bullet nor ballot, but movement is the solution. Not one movement or one organisation but a movement of every stream, ideology, class and section should fight like a united fist. The nation is in crisis and a united, very firm committed, militant movement is the solution”. This was well received.

We have done several experiments after that and got several wonderful responses. Recently in the 2023 Assembly elections, through Yeddelu Karnataka, we were firm on defeating the BJP government.

The entire civil society came together to play a proactive and creative role in election intervention. It contributed to the defeat of the BJP in Karnataka. Several such experiments have taken place. It has been a beautiful journey and we have learnt a lot in this journey. We have received a lot of love and respect from civil society. We are very happy and proud of it.

Q. The BJP agrees with you when you say civil society movements played a big role in its defeat. In the eyes of ideological rivals, you were earlier naxalites in the armed struggle and are now “urban naxals” in civil society. How do you respond?

Sirimane Nagaraj: BJP and Sangh Parivar came up with the term “Urban Naxals” intentionally. Anyone who opposes the BJP and Sangh Parivar’s ideology tooth and nail are “Urban Naxals” in their eyes.

Writers, artists, comedians, activists, Dalit labourers, journalists, and even Jnanpith award winner Girish Karnad was called Urban Naxal. By then UR Ananathmurthy was no more. They have defamed him but if he were alive, they would have called him Urban Naxal too.

In all, whoever opposes BJP and RSS hate politics is being branded Urban Naxals. We have come from the Naxalite movement to a democratic movement so we are democrats, secularists and people who uphold the Constitution, democracy, secularism and inclusivity of India.

Q: Do you regret taking up arms and taking part in the Naxalite movement?

Sirimane Nagaraj: We believed in that path at that time and hence took it up. From the 70s, I was part of big mass movements in Mysuru — labour, and literature movements. But we thought it wasn’t enough and were influenced by Maoist ideology and the Naxalbari arms struggle politics, and accepted it.

There was a time when we had to go incognito and underground. Our experiences then and assessment of our previous decisions and their impact on society made us realise that this wasn’t the way forward. We realised that India had democratic spaces that we weren’t utilising and were getting isolated from society.

We revolted within the CPI(Maoist) party for five years. Our state leadership or central leadership wasn’t willing to listen. They insisted that arms struggle was the only way and they couldn’t withdraw. So we had to part ways. I don’t regret it. We chose one path but when we felt it wasn’t the right thing to do, we came out of it at the right time.

Noor Sridhar: We came out of armed struggle because we didn’t feel it was the right thing to do but there is no regret about joining the movement or working for it. That movement taught us a lot — commitment, sacrifice, simple living, a revolutionary approach, intense feeling, and understanding the crux of Marxism.

It has given a lot to us. There is no ‘one perfect way’. There were several experiments but nothing was going ahead. That’s why Right-wing forces have come up. If you say the Naxalite movement wasn’t correct, then have democratic movements provided the solution? No. Even Ambedkarite, Lohiaite, and Gandhian movements are in crisis, not just the Naxal movement.

Whatever has happened has given us lessons. We don’t regret it but definitely know that armed struggle is not the right path. We have to unite as a civil society and come up with a new form of struggle and evolve. India is under that process. We are happy about joining this journey at the right time.

Sirimane Nagaraj: That (Naxalite) movement showed big results and contributions. It wasn’t futile or wasted. In Karnataka. we worked in the Kudremukha national forest region. Farmers and Adivasis there agree that if not for us, they would have been thrown out of their homes, and evicted.

The region was saved and real development has taken place for the people there because of the Naxal movement, is what the locals say. Across the country, the movement has contributed to art and literary fields. That doesn’t mean armed struggle is the way forward now is our understanding. We have to set a new path with a united movement.

Q: Weeks before Karnataka declared itself a no-Naxal state, Vikram Gowda was killed in an alleged encounter. Are security forces held accountable for these encounters? Are you convinced the law is taking its course?

Noor Sridhar: Definitely no. We have worked with the government to bring the six members into the democratic mainstream. The government, police, and civil society worked together to successfully convince Naxal comrades to come to the mainstream. But this journey started through struggle.

Noor Sridhar: Definitely no. We have worked with the government to bring the six members into the democratic mainstream. The government, police, and civil society worked together to successfully convince Naxal comrades to come to the mainstream. But this journey started through struggle.

When Vikram Gowda was killed, we were very angry and felt it was a heinous crime. We are from this background and can immediately understand which is an encounter, which is false and which is murder. Vikram Gowda’s encounter was very clearly fake and a cold-blooded murder.

We seriously condemned it. We said it was the government’s heartless action but at the same time, we appealed to Naxals that there was no meaning in being stubborn and continuing on this path and losing lives. Very precious lives and very committed people are part of this movement and we appeal that their commitment should be useful to society.

The whole civil society team fought with the chief minister (Siddaramaiah) to stop combing ops and give us an opportunity to convince them and bring them to the mainstream. We also told the CM that an inquiry committee should be constituted into Vikram Gowda’s encounter. He didn’t do it. We continue our demand to order an inquiry on Vikram Gowda’s encounter. Whenever government takes the right path, we will cooperate, when they don’t, we will condemn. We will do both. We won’t take an unprincipled stand on supporting government even when it is wrong.

Q: Both of you have given up armed struggle and play a key role in bringing others to the mainstream. How are you preventing youth from taking up armed struggle or naxalism?

Sirimane Nagaraj: We have multiple affronts that work with student organisations and build youth and student groups. They are our primary focus group. We try to guide them into democratic paths. Of course, youth are inclined towards dynamic and fast paths and we need to come up with a militant movement but we consult with multiple stakeholders to instil political and ideological commitment and shape their farsightedness. The results of our experiments will be shown in the future.

Noor Sridhar: Our intention is not to stop youth from joining the movement. It is not an underworld life or alcoholism or drug addiction that is bad or a sin. Naxalite movement is not like that. This isn’t a bad path. All we are saying is that the path does not bring about revolution. It is also one path of struggle — it is a form of militant dissent. They always have the choice to pick that path and fight but our greater conviction is that this path does not lead to societal changes and only leads to more losses, so it isn’t ideal.

We are more concerned about what is the right way. What path should the youth take up? Formal struggles are of no use today. We need effective struggle but not definitely armed struggle.

We are trying to find a middle ground — a new movement. We are passionately building youth for the welfare of this country and to fight for people. Our focus is on building things, not stopping anything. Stopping something sets a bad precedence. Take Malnad for example, the place where we surrendered, today our Karnataka Jana Shakti association is working marvels.

We have been able to establish networks and connections. Because of that, we could bring Naxals to the mainstream.