“Planned consolidation and development of land can make the city look better. Farmers are sacrificing for the city — they must be treated with empathy,” says LK Atheeq, IAS (Retd) who heads the Bengaluru Business Corridor.

Published Nov 20, 2025 | 8:00 AM ⚊ Updated Nov 20, 2025 | 8:00 AM

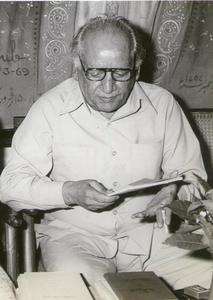

LK Atheeq was influenced by Marxist and left-wing thought — equality, egalitarianism, focus on common people and labour — during his college days.

Synopsis: Political connotations were attributed to LK Atheeq leaving the Karnataka CMO on 4 June 2025. However, he soon took charge of the Bengaluru Business Corridor aimed at reviving the decades-old Peripheral Ring Road project. Additionally, he is also pursuing his passion — translating the poems of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, whose death anniversary falls on 20 November.

His abrupt exit from Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah’s office earlier this year raised eyebrows. Now, retired IAS officer LK Atheeq is heading the Bengaluru Business Corridor aimed at reviving the decades-old Peripheral Ring Road project (PRR).

With over 30 years in public service, LK Atheeq has been a senior advisor at the World Bank, has served in the Prime Minister’s Office and piloted crucial initiatives in the Rural Development and Panchayat Raj department in Karnataka — all while advocating for states’ rights in fair distribution of taxes and federalism.

South First caught up with the bureaucrat who has embarked not just on the PRR but also a personal project too — popularising his translation of renowned Urdu poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz.

Q: Other than being a public servant, you are a coffee connoisseur, a bike enthusiast and now your passion for poetry. Tell us about your translations of Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s poetry.

Urdu poet Chaudhry Faiz Ahmad Faiz (13 Feb 1911 – 20 Nov 1984)

A: I studied in the Urdu medium. My father was an Urdu teacher in Pavagada and Koratagere in Tumakuru. We had many Urdu books at home, and he subscribed to monthly magazines like Huda and Huma, which I read cover to cover. As a child, I would sit while he tutored senior students and listen to him teach poetry — that’s where my love for Urdu poetry began.

After I entered the service, I read Urdu poetry on and off. At the academy in Mussoorie, I encountered Faiz Ahmed Faiz. Until then, we mainly knew Ghalib, Allama Iqbal, Mir Taqi Mir, and Josh Malihabadi. Faiz was different — a revolutionary poet who blended romanticism and revolution, without sloganeering. His poems stayed with me.

Q: You translated selected Faiz poems into Kannada. How did you pick the poems?

A: I chose those easier to translate — mostly nazm (free verse). Ghazals are difficult because they require rhyme in Kannada too. As a Urdu mother-tongue who learned Kannada later, I’m aware of my limitations. So I translated simpler, independent verses that I could render faithfully.

Q: Given your long career in the social sector — water, RDPR, education — did Faiz’s socialism resonate with you? He was a communist, and it reflected in his progressive writings.

A: I think so. There’s a well-known line: when you’re young, if you’re not a communist, something is wrong with you; and if you stay one when you’re old, something is wrong too.

In college, we were influenced by Marxist and left-wing thought — equality, egalitarianism, focus on common people and labour. Faiz wrote about working people, and that creates a connection.

Q: But Faiz also wrote against tyranny, dictatorship, and governments that refused accountability. For someone who was entrenched in the government services for decades, were his poems contradictory to your work?.

A: In service, I’ve always tried to be with the people. When I was the CEO of Zilla Panchayat or DC in Mandya and Hassan, I kept my doors open. When people came with complaints against Tahsildars or village accountants, I’d first hear them and act — subject to verification. I would question officers in public and settle matters if I could. Accountability is essential; bureaucrats are paid with taxpayers’ money. Poetry that speaks for the people resonates with that spirit. I don’t see a contradiction between being a government servant and admiring Faiz.

I started translating Faiz in 2000. When I was CEO in Uttara Kannada, especially in Ankola, there was a rich intellectual community. I introduced Faiz to friends who knew Ghalib and Iqbal but not Faiz. They urged me to translate. The poem, Bol, I translated it on a beach and showed to Vishnu Naik, who encouraged me.

Raghavendra Prakashana of Ankola published it. Chandrashekhara Patil (Champa) wrote the epilogue; Dr GS Shivarudrappa wrote a foreword and released the book in Mandya to a large audience. I wasn’t very proficient in Kannada initially — I studied formally only till fourth standard in Kannada and later passed a departmental exam — so critics like Shivarudrappa helped improve the work. Now, I plan to record the Urdu originals and my Kannada translations as a podcast.

Q: You’ve revived the Peripheral Ring Road (PRR) and you actively engage citizens on social media, invite people to meetings and verify concerns. Does that approach help separate genuine grievances from rabble-rousing?

A: Being on social media — I use it primarily to put out government information. I don’t put personal updates; I use my account to inform people about work. I get cues, respond, but not everyone is on Twitter (now X), and it’s largely in English. So we put information in Kannada too, and I go to the field — I prefer to sit with farmers.

This project has been stalled since 2005. The final notification for the acquisition of 1,810 acres was issued in 2007. We’re now in 2025 and reaching 2026 — 18–19 years — and still, land hasn’t been acquired, compensated or a road built. Farmers deserve fair compensation, but there are legal problems: the rates and guidance values haven’t been revised in parts for 7–8 years; expectations are different.

We’ve tried to provide options. After discussions with the Deputy Chief Minister and the Chief Minister, and taking it to Cabinet, we provided five options to landowners: commercial or residential sites, TDR, cash, and, in some cases, developed land instead of cash.

We present draft awards to farmers and ask for feedback: ‘What is your opinion?’ When they say they need more, we flag those demands to higher levels. Some 30 to 35 petitions are also in courts. We are balancing legal, financial and social issues while trying to build the road — it’s important. For example, the journey from BIEC to Yelahanka is 19 km as the crow flies but can take 1.5–2 hours by road because there’s no direct route.

Q: Many farmers say land is more than an economic asset. How do you address those emotional concerns?

A: This PRR is an infrastructure project, so we are using only a 100-metre corridor. Mostly in areas that have become urban or are urbanising. About 25 percent of land identified for acquisition falls in the ex-BBMP limit; much of the rest is within 5 km of municipal limits and under BDA planning. Over time, that land won’t remain agricultural.

The road will enhance residual land value — about 70% of land losers will benefit because what they keep will appreciate. But some lose everything; those cases are very difficult. There are also irregularities: people have illegally built layouts and sold small sites inside notified areas, thinking the project was dead. Those buyers get little compensation. We need to settle such peculiar cases with sensitivity.

Planned consolidation and development of the remaining land can make the area and city look better. Farmers are sacrificing for the city — they must be treated with empathy.

Q: You spent five years in RDPR — among the longest stints in a single department. Any takeaways?

A: RDPR gave me a lot of satisfaction. I have spent the second-longest tenure in RDPR in Karnataka’s history. When I joined, Karnataka was generating about 8 crore person-days under MGNREGA; we took it to 16 crore. Each 1 crore person-days equates to roughly ₹5,500 crore flowing into Karnataka — 90% from the Union government, 10% from the state. We used it to restore lakes, kalyanis, irrigation assets, social forestry, and village infrastructure like schools and playgrounds. Workers could earn ₹25,000–₹30,000 a year through this work. During the pandemic, when MGNREGA briefly stopped for about 15 days, the complaints made it clear how critical it was as a safety net.

Q: Tell us about your time at the World Bank and how it influenced your thinking on finance and development.

A: I worked as Senior Advisor to the Executive Director representing India, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Sri Lanka. We saw loan proposals from developing countries worldwide and argued the borrowers’ case at the Board. It was an excellent exposure to international development finance.

We argued that ownership of the World Bank needs reform — developed countries hold disproportionate shares (the US alone about 15%; India about 3%, China about 5%). Developing countries borrow and fund the Bank’s income; yet ownership and governance don’t reflect that.

World Bank survives on the interest that borrowing countries like India pay it. We pushed to reduce loan conditionalities and to cut approval timelines — projects were taking two to three years from preparation to approval; we argued for six to eight months. There were some improvements.

Q: You’ve argued for the fiscal rights of contributing states like Karnataka. What should a Finance Commission consider?

A: ‘Fair share’ is a better word than compensation. Redistribution is built into our Constitution under Article 280. Now, when you say ‘allocate,’ it means not everything we give should come back to us. Some amount of redistribution is required. Redistribution is an accepted principle globally, and nobody disputes that.

States like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh (UP) should get more than what they contribute. States like Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana should get a little less than what we contribute — that’s how a surplus is generated and reinvested in those states. This contributes to more balanced regional development. Fair enough, nobody disputes that. However, the question is: in what proportion?

Because of the disproportionate weight given to the per capita income of states, states like Karnataka are losing out. Today, for every ₹100 generated in Karnataka, only about ₹13–15 comes back to us. That proportion needs to change — that’s the main argument we’ve made.

We’ve also argued that cities like Bengaluru are growth centres and are attracting a workforce from across the country. People in Bengaluru today come from Odisha, Bihar, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan — from everywhere. We provide them employment. Why do they come here? Because the wage difference is very high. Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Mumbai, Pune, Chennai — these are growth centres, and they also need investment. Urban areas face huge investment deficits. There are governance issues as well.

Per capita income is an average concept. If you take the average per capita income of Karnataka and compare Yadgir with Bengaluru, there is a six-times difference.

We then need to invest more in districts like Yadgir, which means more money is needed for North Karnataka, especially Kalyana Karnataka. For that, too, we need more resources from the pool we contribute to. That would make it fairer.

Another — slightly controversial — point: over the years, states receiving greater Finance Commission grants, sometimes twice or thrice what they contribute… their per capita income still has not caught up.

For example, UP gets about 2.7 times what it contributes — for every ₹100 contributed, ₹272 goes back to it.

But over the last 30–40 years, their per capita income has not caught up, nor have human development indices.

Q: You worked in the PMO with Dr Manmohan Singh and in the CMO with Siddaramaiah. What are your takeaways?

A: I spent around five-and-a-half years in the PMO across UPA-1 and UPA-2 — a rewarding period. I had the opportunity to work with Dr Manmohan Singh, a very learned man.

Dr Manmohan Singh. (X)

We were involved in formulating MGNREGA, RTE, the Food Security Act, the National Health Mission, and JNNURM. Under UPA, revenues in the country were buoyant, economic growth averaged 8–8.5%, and social sector programmes expanded.

An anecdote from earlier in my career: when Siddaramaiah was Finance Minister in 1995, and I was a deputy secretary in the finance department. I had written a note in English. Generally, these don’t reach the Finance Minister’s office, but this particular note did. The then Finance Minister Siddaramaiah called my boss and insisted that the note be written in Kannada. Sometimes, he would get angry if government communication wasn’t in Kannada and send files back. I worked more closely with him after joining the CMO in 2016.

Q: You were appointed ACS post-retirement and got an extension this January, but left midway. Why did a close aide of the Chief Minister step down?

A: I felt people should step aside at some point. I wanted more time with family and to pursue other things. I planned to leave everything, but the Chief Minister asked me to take on this project — the PRR. Now I can give it my full attention; it has progressed significantly.

Q: Transition from social sector to finance to now infra — naturally, the next stop is politics? So many bureaucrats are taking up politics. Is that something you are interested in?

A: I’m focusing my attention on this project, which will take some time. No other plans as of now.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).