This isn't the first time the BJP has pooh-poohed a social welfare scheme announced by another party, only to adopt it under a different name.

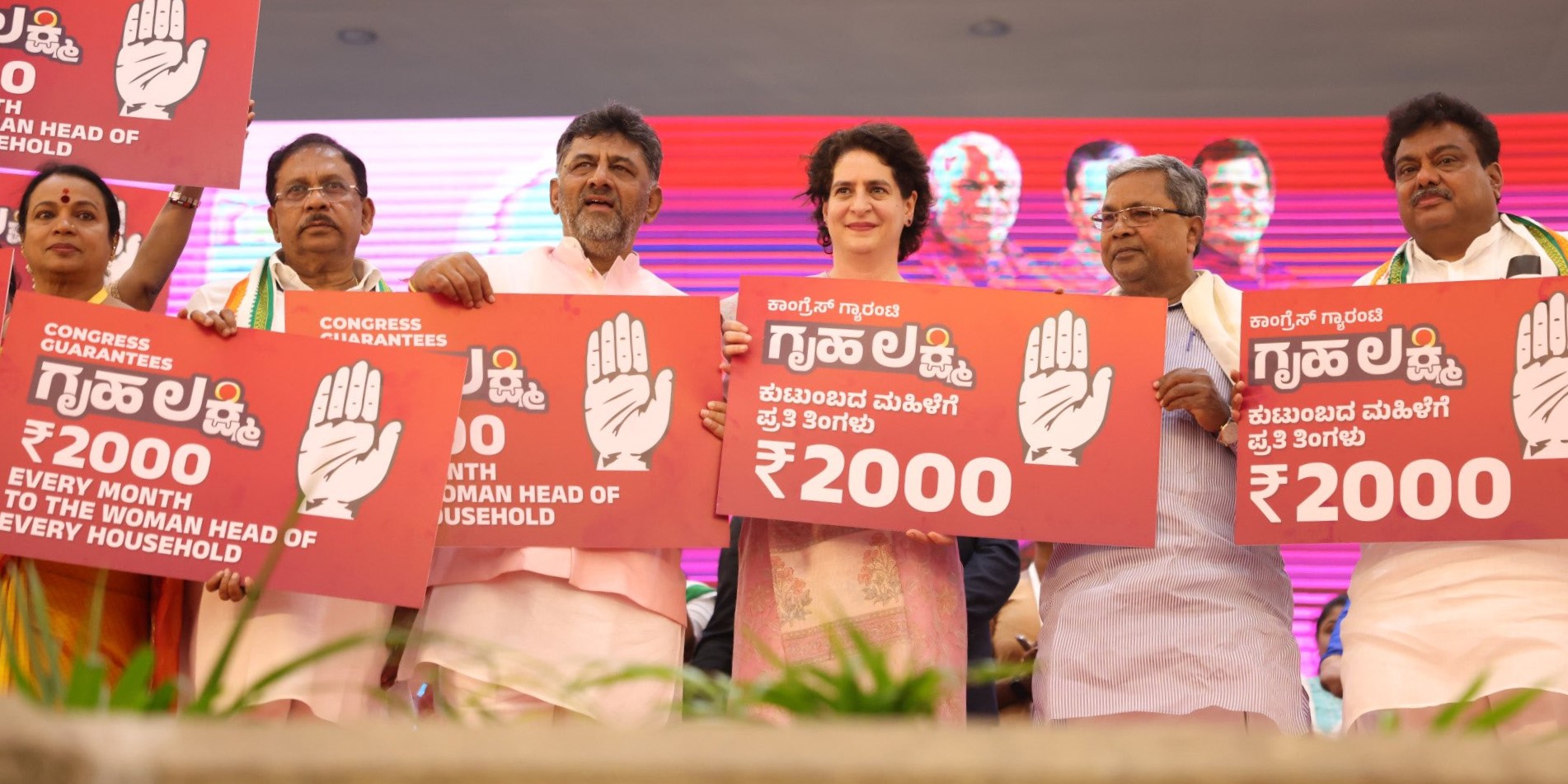

AICC general secretary Priyanka Gandhi with Congress leaders DK Shivakumar and Siddaramaiah at Palace Grounds in Bengaluru on Monday, 16 January, 2023. (Supplied)

When Congress General Secretary Priyanka Gandhi announced her party’s poll promise of ₹2,000 per month for every woman head of a household, it took the BJP in Karnataka barely minutes to mock Priyanka, her party, and the party’s promise.

It, however, also took the BJP barely two days to announce its own ₹2,000 per month financial assistance scheme to women of Below Poverty Line (BPL) families.

In less than 48 hours, BJP had jumped on to the bandwagon of what its own leaders, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi, have derided as “revdi culture”/”freebies culture”.

The Karnataka Congress scheme — Gruha Lakshmi Yojana, announced on 16 January — assures an unconditional disbursal of ₹2,000 to homemakers as Direct Benefit Transfer, or DBT.

It will be a landmark step towards Universal Basic Income (UBI), if implemented in its assured form. UBI was mooted by the UPA-2 government at the Centre ahead of the 2014 Lok Sabha elections.

Karnataka Revenue minister R Ashok, on 18 January declared that BJP’s own scheme — Gruhini Shakti — would be announced as part of the pre-election budget.

हमारे देश में मुफ्त की रेवड़ी बांटकर वोट बटोरने का कल्चर लाने की कोशिश हो रही है।

ये रेवड़ी कल्चर देश के विकास के लिए बहुत घातक है।

इस रेवड़ी कल्चर से देश के लोगों को बहुत सावधान रहना है: PM @narendramodi

— PMO India (@PMOIndia) July 16, 2022

Chief Minister Basavaraj Bommai defended the move, insisting that he had spoken about such a scheme being under consideration a couple of days before Congress made its announcement.

“The Assam government has implemented a similar scheme which we can replicate,” Bommai told reporters in Shivamogga on 18 January when barely two days ago he had deemed the Congress poll promise “irresponsible and irrational”.

This isn’t the first time that the BJP has pooh-poohed a social welfare scheme announced by another party, only to eventually adopt it under a different name or format. If anything, this has been BJP’s consistent pattern.

Take, for example, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Scheme (MGNREGS).

In a thunderous speech in the parliament in February 2015, Prime Minister Modi declared UPA’s flagship employment guarantee scheme as the “monument of UPA’s failure”.

Six years later, in February 2021, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, in the same Parliament, took pride in the high expenditure under the scheme.

During the Covid-19 pandemic-induced lockdown in 2020, demand for work under MGNREGS saw its biggest surge. The Modi government relied on the “monument of UPA’s failure” to offset the shock of the lockdown, and the resultant loss of jobs and incomes among India’s poorest.

It was in January 2019 that Congress announced its big poll promise: A minimum income guarantee scheme.

On 28 January, 2019, then Congress president Rahul Gandhi said the scheme intended to ensure minimum income guarantee for every poor person in the country by means of DBT.

The details and name for the scheme — Nyuntam Aay Yojana, or simply NYAY — came only in March. Unlike the UBI scheme, NYAY was only meant to benefit the poorest families.

NYAY sought to assure ₹6,000 per month for every poor household in the country. The scheme sought to hand over ₹72,000 per year to 20 percent of India’s population. The scheme sought to bridge the gap between the actual income of India’s poorest families and what their minimum income per month ought to be.

BJP was quick to dismiss the assurance as “not meant to be implemented” and “off the cuff”.

But on 1 February, 2019, the Modi government, as part of the interim Union budget ahead of the Lok Sabha election, announced the PM Kisan Samman Nidhi — a minimum income support scheme of ₹6,000 per year transferred to poor farmers via DBT.

The first of its kind minimum income support scheme, it was similar to what was proposed as minimum income guarantee under NYAY, but for a smaller, more specific section of the poor.

Although Prime Minister Modi leads the charge against what he terms “revdi culture”, deriding social security and welfare schemes to “freebies”, direct benefit transfers have given the BJP immense electoral gains.

Karnataka Chief Minister Bommai himself gave testimony of this when he said his Gruhini Shakti scheme was a replica of a BJP-government scheme in Assam.

The Orunodai scheme was launched by the BJP government led by Sarbananda Sonowal in Assam in October 2020, months ahead of the Assembly polls in April 2021.

Despite the rising cost of living, increased fuel prices, and hikes in LPG prices, the direct cash transfer helped BJP beat anti-incumbency and clinch the election.

What began as a transfer of ₹830 directly into the bank accounts of women in 19.10 lakh poor households, has now been increased to ₹1,000 because the BJP gained big from the welfare scheme.

The Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) announced by Modi in March 2020 following severe economic distress due to the pandemic-induced lockdown came to be the single-largest contributor to BJP winning a second term in Uttar Pradesh.

The scheme assured 5 kg of rice or wheat and 1 kg of pulses to the “poorest of the country”. Beneficiaries of the scheme — largely women — are credited with voting en masse for the BJP in gratitude.

The free ration scheme is only a slight modification of the heavily subsidised or free grains schemes of various state governments, including Karnataka’s own Anna Bhagya Scheme introduced by the Siddaramaiah-led Congress government in 2013.

The BJP in Karnataka had lashed out at the scheme from day one. In May 2021, the BJP government in Karnataka scrapped the flagship programme of the Congress and merged it with the Union government’s PMGKAY.

Parties promising monetary assistance ahead of elections is not new. All India Trinamool Congress (AITC) in its West Bengal poll manifesto promised ₹500 and ₹1,000 for women heads of families in the general category and SC/ST families, respectively.

The party made a similar poll promise when it contested in the Goa election, assuring ₹5,000 per woman head of family.

Assurance of financial assistance has been the Aam Aadmi Party’s (AAP) consistent poll startegy. The party announced ₹1,000 for women during its campaigns for the Punjab, Himachal Pradesh as well as Gujarat Assembly elections.

In Tamil Nadu, both the AIADMK and DMK announced assured cash assistance for women as part of their election manifesto for the Assembly polls.

The latest Congress poll promise of ₹2000 as “UBI” to homemakers in Karnataka follows the party’s ₹1,500 per month promise for women between the ages of 18 and 60 in Himachal Pradesh. The difference in Karnataka is the party’s assurance that it will be an “unconditional universal basic income”. None of these parties have mocked these proposals as “freebies culture”, instead have demanded the the ruling dispensation put more money into the hands of India’s poor to help them.

Clearly, the BJP, despite its perceived contempt for “freebies” has reaped great electoral benefits out of what its leaders deem “Revdi culture”.

Why then does the BJP ridicule other parties when they make similar promises? One may deem it hypocritical but that would be political naivety.

“If all parties make such promises, the schemes lose their novelty, which is why Prime Minister Modi likes to keep the freebies discussion going on simultaneously. So if other parties fall for that discussion and refrain from making similar announcements, then these transfers become unique to the BJP,” opined Prof Narendar Pani, dean, School of Social Sciences, at the National Institute of Advance Studies.

“Otherwise, there is no reason to attack freebies when BJP itself is giving them and they are a big part of their poll promises,” Prof Pani told South First.

With elections scheduled in nine states in 2023, one should be more surprised if the BJP — whose leaders claim to vehemently oppose “freebie culture” — do not play catch up with other political parties and their poll promises.

If Karnataka Congress poll promise is a step towards Universal Basic Income — hailed as serious and feasible solution to India’s poverty in the 2016-2017 Economic Survey of India — it is only a matter of time before the BJP will follow suit with a similar promise in other poll-bound states and eventually at the national level.

That’s what the BJP’s pattern of behaviour so far would suggest.

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 25, 2024

Jul 24, 2024

Jul 23, 2024