Published Dec 12, 2024 | 7:00 AM ⚊ Updated Dec 12, 2024 | 7:00 AM

A child in a hospital. Representation image. (iStock)

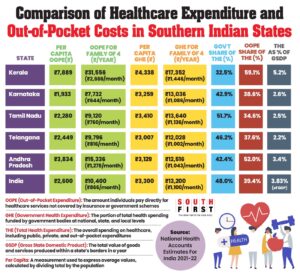

Kerala, long celebrated for its robust healthcare system, faces a puzzling paradox. Despite being the second-highest in per capita government health expenditure in India at ₹4,338 in 2021-22, the state records the country’s highest out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE), reflecting a heavy reliance on private healthcare.

According to the National Health Accounts (NHA) 2021-22, OOPE in Kerala constituted 59.1% of the state’s Total Health Expenditure (THE), amounting to ₹28,400 crore.

This translates to an average of ₹7,889 per person annually.

Health expenditure.

For a family of four, this equals ₹32,000 per year, or about ₹2,666 per month —significantly higher than in neighboring states like Karnataka, where the per capita OOPE was a modest ₹1,933.

On the government’s part, spending in Kerala reached ₹15,618 crore (32.5% of THE), equating to ₹17,352 annually for a family of four, or ₹1,446 per month.

Despite this substantial investment, the financial strain on households remains glaring.

While Kerala spends 5.2% of its Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) on healthcare — the highest in the region — the reliance on private healthcare remains pervasive.

It comes from the point that even though the state’s GSDP on healthcare spending is 5.2%, the second-highest in the country after Uttar Pradesh. The government expenditure to GSDP is only 1.7%, while OOPE to the GSDP is 3%.

Private facilities, often costlier than their public counterparts, drive up household costs, overshadowing the benefits of government investment.

In comparison, Tamil Nadu effectively curbs OOPE to ₹2,280 per capita through strong public healthcare programmes, spending a modest 2.5% of its GSDP on health.

Similarly, Karnataka balances public and private healthcare to keep OOPE at ₹7,732 annually for a family of four — significantly lower than Kerala.

The National Health Accounts (NHA) report shows Kerala’s OOPE as a share of Total Health Expenditure (THE) fell from 65.7% in 2020-21 to 59.1% in 2021-22.

However, this still indicates a persistent dependence on private healthcare, with limited success in shifting families towards affordable public options.

So what explains Kerala’s OOPE when government health spending per capita in the state is so high?

Kerala has a higher average cost of healthcare compared to neighbouring states or other parts of the country, except perhaps for some big cities.

For example, if you compare the cost of each treatment or procedure, it is generally higher in Kerala. This is largely because Kerala traditionally has higher wages, making the overall cost of living higher.

“Kerala has one of the highest average wages for both men and women in the country. Everything is interconnected here — higher wages, higher expenditures, and higher costs. You cannot view higher healthcare spending in isolation; it’s also a state with relatively high per capita income and a higher cost of living compared to most states,” Kerala-based health economist Dr Rijo M John told South First.

For example, in Kerala, nurses generally earn higher salaries than in other states. This means that the overall human resource cost in Kerala is higher, which naturally increases the per capita cost of providing healthcare.

He also pointed out that Kerala, additionally, has a distinct consumer-oriented economy, where people tend to spend more.

Coupled with this, Kerala has a significantly higher health-seeking behavior compared to most other states.

This could mean higher out-of-pocket expenditure, higher government expenditure, or both.

“This is a critical factor that sets Kerala apart. People here tend to seek medical care even for minor health issues. For example, if someone in Kerala has a fever, they are likely to seek formal care and consult a doctor immediately. Contrast this with many parts of North India or other states, where families often delay seeking healthcare until a condition becomes critical,” said Dr John.

This high health-seeking behavior naturally leads to higher OOPE as well as government healthcare expenditure. With such a culture, absolute healthcare costs — both personal and governmental — are bound to be higher.

“So, in my opinion, it’s not a dichotomy,” Dr John said.

Kerala leads India in the prevalence of diabetes, affecting 27% of adult males and 19% of adult females — significantly higher than the national average.

The state also records a high incidence of coronary artery disease (CAD), with age-adjusted mortality rates of 382 per 100,000 men and 128 per 100,000 women.

Obesity levels in Kerala are among the highest in the country, with 44% of women and 40% of men classified as obese, contributing to a range of health complications.

Additionally, cancer has become a pressing concern, with incidence rates climbing from 135.3 per lakh in 2016 to 169 per lakh in 2022.

The Thiruvananthapuram Regional Cancer Centre alone has seen a significant rise in new cases over this period.

This escalating burden of lifestyle diseases has placed increased demand on Kerala’s healthcare system, particularly impacting the working-age population and driving up medical expenses.

Dr John said that this trend can be attributed to several factors. Kerala is known for certain unhealthy dietary habits, including a fast-food culture, which leads to diet-related obesity. While tobacco and alcohol use in Kerala are below the national average, diabetes, hypertension, and dietary issues are more prevalent in the state.

The National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) also highlights that abdominal obesity is highly prevalent, particularly among males in Kerala.

“These factors — dietary habits, obesity, and high prevalence of diabetes and hypertension — are all contributing to the increased healthcare expenditures in the state. There’s no doubt about it,” explained Dr. Rijo M. John.

Culturally too, there is greater acceptance of obesity, with adages that equate prosperity with girth.

Also, Kerala’s rapidly aging population is a key driver of the state’s rising OOPE on healthcare.

As of 2021, 16.5% of Kerala’s residents were aged 60 and above — a figure projected to rise to 22.8% by 2036, significantly surpassing the national average of 15%.

By then, one in five individuals in the state will be a senior citizen, reflecting a marked demographic shift.

An older population correlates with higher rates of chronic diseases and multi-morbidity, affecting 52.2% of Kerala’s elderly compared to the national average of 23.3%.

These conditions necessitate regular medical interventions, long-term treatment and specialised care, all of which increase OOPE.

Additionally, many elderly individuals, particularly widowed women without independent income or assets, rely heavily on family members for financial support. This dependence strains household budgets as families bear the direct cost of healthcare, exacerbating the burden of OOPE in the state.

Dr John explains that in states with better healthcare infrastructure and a population with high health-seeking behaviour, it is only expected that healthcare expenditure would be higher.

When per capita healthcare expenditure is high in absolute terms, it reflects both higher government spending and higher spending from private citizens.

“This isn’t just about healthcare; it’s like when you look at crime statistics across the country. For example, crime rates are often higher in Kerala compared to other states. But just because crimes aren’t reported in other states doesn’t mean they don’t exist — it’s about awareness and reporting. Similarly, health-consciousness in Kerala leads to higher reporting of illnesses, including outbreaks like flu or viral infections. While other states may experience similar issues, they may go unnoticed simply because people aren’t as aware or health-seeking,” said Dr John.

Sheeja Santosh, 49, who ran a tailor shop catering to women in Pala town of Kottayam district, was a childless widow. She had neglected her high blood pressure, and when she went to the doctor at the private Mar Sleeva hospital in Cherpunkal in March 2024, she was told that she needed urgent dialysis. She was admitted there, and her bill of Rs42,000 for a week’s stay was taken care of by her sisters in law.

She continued to work at her tailor shop and go for dialysis twice a week, first to Mar Sleeva and later at Marian Hospital, another private hospital in Pala town.

When the fistula inserted in her arm for dialysis got blocked in October, she was in a quandary as she could not afford to keep relying on relatives.

She decided she had had enough, and discontinued dialysis after October 30, 2024.

She could have received free dialysis at the KM Mani Memorial Government Hospital in Pala, but she had no Aadhaar identification.

Her failing health did not allow her to pursue Aadhaar registration.

She passed away on 27 November, 2024, unable to find the means to fund her treatment in a state that spends so much on healthcare.

(Edited by Rosamma Thomas)