Published Sep 03, 2025 | 7:00 AM ⚊ Updated Sep 03, 2025 | 11:17 AM

When pharmacists cannot read a prescription, they must contact the doctor for clarification, which delays the start of treatment.

Synopsis: The Punjab and Haryana High Court ruled that a legible medical prescription and diagnosis is not just good practice but a part of the fundamental right to health. While experts and doctors view the order as a positive step, many argue that top-down mandates alone cannot address the complex realities of healthcare system. Doctors say that meaningful reform must be comprehensive and address root causes.

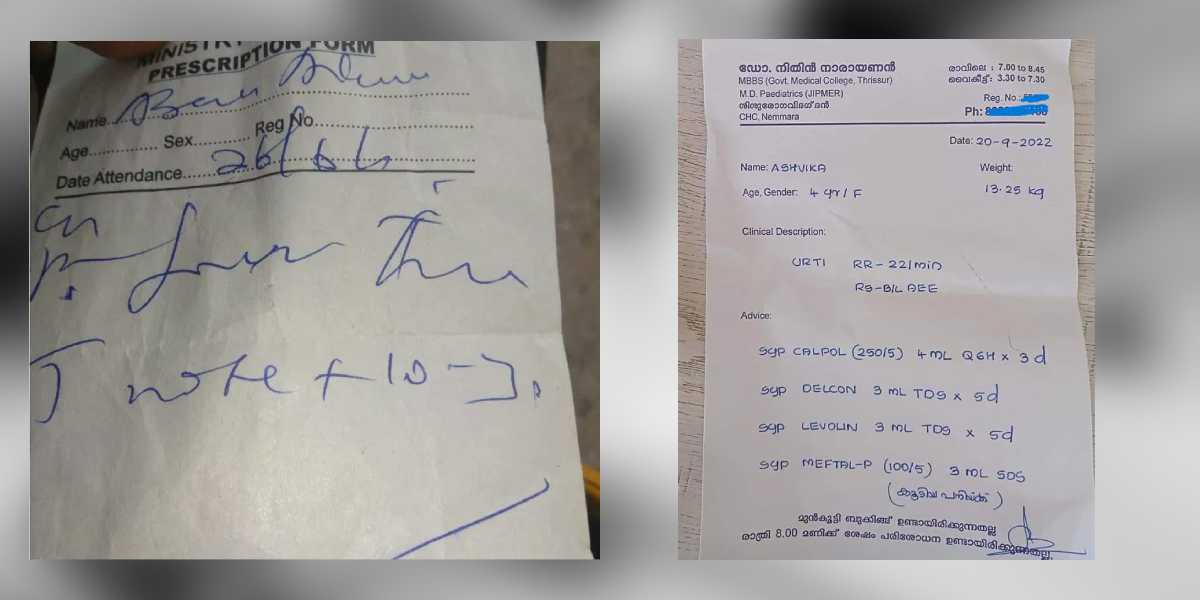

Many of us have stared helplessly at a doctor’s scribbled prescription, unable to decipher a single word, only to rely on the pharmacist who, within seconds, decodes it and hands over the medicines.

Now, the Punjab and Haryana High Court has stepped in, ruling that a legible medical prescription and diagnosis is not just good practice but an integral part of the fundamental right to health under Article 21 of the Constitution.

Calling it “shocking” that in an age of technology and digital tools, doctors still write prescriptions by hand that few can read, Justice JS Puri stressed that illegible handwriting creates confusion, inefficiencies, and even risks to a patient’s life. The court directed the government to ensure steps are taken towards clear, accessible, and preferably digital prescriptions.

While the Punjab and Haryana High Court’s ruling represents an important step toward patient safety and rights, the path to legible prescriptions requires more than judicial intervention. It’s multifaceted, where lasting change will require a comprehensive transformation of India’s healthcare system

Dr Sudhir Kumar, a neurologist at Hyderabad-based Apollo Hospital, outlined the serious consequences that stem from scribbled prescriptions. “There are several types of mistakes that can occur in prescriptions, which can have serious consequences for patients,” he explained.

“Medication errors are among the most dangerous; the wrong drug, incorrect dose, or improper route of administration may be prescribed. For example, abbreviations like OD (once daily) or BD (twice daily) are often misread, leading to patients taking medicine incorrectly,” Dr Kumar told South First.

The ripple effects extend far beyond simple confusion. When pharmacists cannot read a prescription, they must contact the doctor for clarification, which delays the start of treatment. Incorrect drugs or doses can cause side effects or allergic reactions, while patients may not receive the intended benefits, defeating the purpose of prescribing medicine in the first place.

The financial burden is equally significant.

“Mistakes can lead to extra consultations, hospital visits, or treatments for side effects, increasing the financial burden on patients,” Dr Kumar said. Perhaps most concerning is the impact on patient compliance: “Patients who do not understand their prescriptions may skip doses or stop treatment altogether, losing trust in the doctor and the healthcare system.”

The legal implications are also serious. “If a prescription error causes harm, the patient has the right to take legal action, placing liability on the doctor. While the patient suffers most of the harm, the onus of responsibility rests with the prescribing physician,” Dr Kumar warned.

While experts and doctors view the high court’s order as a positive step, many argue that top-down mandates alone cannot address the complex realities of India’s healthcare system.

Dr Parth Sharma, a community physician and public health researcher, provides a more nuanced perspective on the underlying issues.

“Every medical student in India is formally taught how to write a prescription as part of the pharmacology course, usually in their second year before they even enter clinical postings. So, if every doctor graduating in this country has been taught the skill and yet many prescriptions remain illegible, the question is why it’s not being practised,” Dr Sharma pointed out.

The answer, according to Dr Sharma, lies in systemic problems rather than individual negligence.

“One major issue is linked to small clinics and nursing homes. Many nursing homes have their own pharmacies, and the prescriptions are written in such a way that only their pharmacist can understand the prescription and dispense the medication. Similarly, in small clinics, some doctors write in a manner that ties patients to a particular pharmacist, with the doctor often getting a cut from the sale. For example, a medicine costing ₹500 may give a doctor a ₹50 commission.”

The practical challenges facing healthcare providers cannot be ignored. Dr Sharma highlighted the overwhelming patient loads that many doctors face daily.

“The practical reality is that doctors in busy clinics see hundreds of patients a day. Writing a neat prescription in block letters takes more time than scribbling quickly, and so it gets skipped.”

This workload issue is particularly acute in government facilities. “It’s a failing public health system that lies at the root of this entire issue. If you walk into a corporate or large private hospital, you’ll almost never see a scribbled prescription. Why? Because each doctor in their outpatient departments handle maybe 20–30 patients at a time. The problem of illegible prescriptions emerges mostly in government facilities and low-level private setups,” Dr Sharma explained.

The human resource crisis is at the heart of the problem.

“At its core, the problem is human resource scarcity. Whether it’s violence against doctors, lack of empathy in healthcare, or poor quality of care—it all stems from the fact that we simply don’t have enough competent doctors, nurses, or allied health workers. Expecting a doctor to see 400 patients a day is unrealistic.”

While digitalisation might seem like an obvious solution, Dr Sharma cautions against viewing technology as a panacea.

“Even with digitalisation, if one doctor is still overloaded with hundreds of patients, errors will persist. In fact, electronic systems can bring new risks like copy-paste errors. Technology is not a magic pill.”

He draws from personal experience to illustrate the deeper issues: “I studied at one of the most prestigious medical colleges in North India, in the national capital. Even there, we had no electronic medical records. Everything—from blood test results to doctors’ notes—was paper-based. If leading government hospitals remain stuck on paper years after Ayushman Bharat, how will court orders alone change anything?”

The solution, according to Dr Sharma, requires fundamental changes in medical education and ethics.

“The second, equally important issue is the weak foundation of medical ethics in our education system. Human life is often treated as dispensable, instead of recognising that every prescription carries the potential to save or harm. A study published in The Lancet showed that poor quality of care kills more people than lack of access to care—meaning, in some cases, doctors can cause more harm than the disease itself.”

Despite the challenges, both doctors interviewed offer practical solutions that could be implemented immediately. Dr Kumar advocates for simple but effective practices that he has followed throughout his career.

“As doctors, our main responsibility is to help patients recover from their illness efficiently and safely. Every doctor wants to do their job properly, and a key part of that is ensuring patients leave with a clear understanding of their treatment,” he said.

Dr Kumar shared his approach: “I was trained at CMC Vellore in the importance of clear prescriptions—writing drug names in capital letters reduces errors and makes the instructions unambiguous. When I started at Apollo Hospital, I continued this practice, ensuring prescriptions included the drug name, dosage, timing (e.g., 9 a.m., 9 p.m.), before or after meals, and duration.”

He proposed two immediate solutions: “First, in today’s computerised world, doctors could type and print prescriptions. If that’s not feasible in rural areas, then at the very least, prescriptions should be written in capital letters—a practice I have followed for over 30 years. Even when seeing 80–100 patients in under five minutes, it is possible to write the diagnosis and medicine clearly without taking much time.”

The second solution involves standardising communication: “Abbreviations should be standard and explained where necessary. While terms like BP (blood pressure) or OD/BD (once/twice daily) may be familiar to doctors, patients often do not understand them. Including a short explanation at the bottom of the prescription can help prevent confusion.”

Both doctors emphasised that prescription legibility is just one component of comprehensive patient care. Dr Kumar stressed the importance of clear communication beyond just writing: “Many patients stop taking long-term medications, such as for hypertension, diabetes, or epilepsy, after the prescribed duration ends—sometimes with serious consequences. Even if the prescription is written for one month, doctors must explain that these medicines are often lifelong and should not be stopped without guidance.”

Dr Sharma cautioned against viewing prescription legibility in isolation: “If improving patient care is the objective, solutions cannot work in silos. Often, we see piecemeal fixes presented as if they were the golden key to solving everything. But illegible handwriting is only one part of the problem—the quality of the prescription itself is just as important.”

He provided a compelling example: “If a patient comes with a viral infection, the real issue is not whether the doctor writes ‘antibiotic’ in scribbles or in block letters. The real harm lies in prescribing antibiotics unnecessarily in the first place. So, while legibility matters, accuracy matters even more.”

Dr Sharma warned that rigid enforcement without addressing systemic issues could backfire.

“Rigid enforcement of such orders risks unintended consequences. Doctors may resort to stamps with pre-written prescriptions for multiple patients—covering paracetamol, multivitamins, antibiotics, or steroids—simply to protect themselves. This could worsen the problem, leading to overprescription, dosage errors, and harm to patients.”

He emphasised that the issue requires understanding rather than punishment: “Often the people issuing orders on healthcare policies have lived in urban areas and are not up to date with what actually happens on ground in clinics and hospitals. This leads to decisions that are ideal on paper but impractical to implement. But if an order cannot be implemented, it becomes meaningless.”

Both doctors agree that meaningful reform must be comprehensive and address root causes. Dr Sharma advocated for systemic change: “What we need is nothing short of a transformation in medical education, where ethics and quality of care are deeply ingrained, alongside a comprehensive national policy for managing human resources in healthcare. Without that, no amount of digitalisation, AI, or tech-driven reforms will solve the problem.”

He also noted that the challenge lies in implementation. “Any reform has to start from understanding what is happening on the ground. If we begin from the realities of clinical practice and then implement guidelines across the system, it could lead not only to better prescription practices but also to broader improvements in the quality of healthcare,” Dr Sharma concluded.

Dr Kumar emphasised that the solution starts with individual responsibility combined with systemic support: “Writing clearly requires only a few extra seconds, but overworked doctors may not always manage this. However, carelessness is not an excuse. Clear instructions, proper explanation, and legible writing together reduce errors, prevent treatment failures, and ensure patient safety.”

(Edited by Amit Vasudev)