Published Nov 09, 2025 | 9:08 PM ⚊ Updated Nov 12, 2025 | 6:59 PM

In a world where skin health advice travels faster than fact checks, dermatologists are battling a new breed of misinformation merchants.

Synopsis: India is on the brink of a digital dermatology crisis, as unqualified influencers and unethical endorsements promote unsafe skin treatments online, warned a panel of experts at South First’s Dakshin Health Summit. They said social media has become a breeding ground for “digital quackery” and called for stronger enforcement of medical ethics, greater public awareness in regional languages, and responsible engagement by doctors to counter misinformation and protect public health in the influencer era.

Social media is changing the face of medicine in India. Dermatologists are now among the most followed medical professionals online.

However, alongside their rise, a dangerous trend has emerged: unqualified influencers promoting unsafe skin treatments, doctors endorsing products for money, and a flood of do-it-yourself (DIY) videos turning chemical peels and bleaching creams into home experiments.

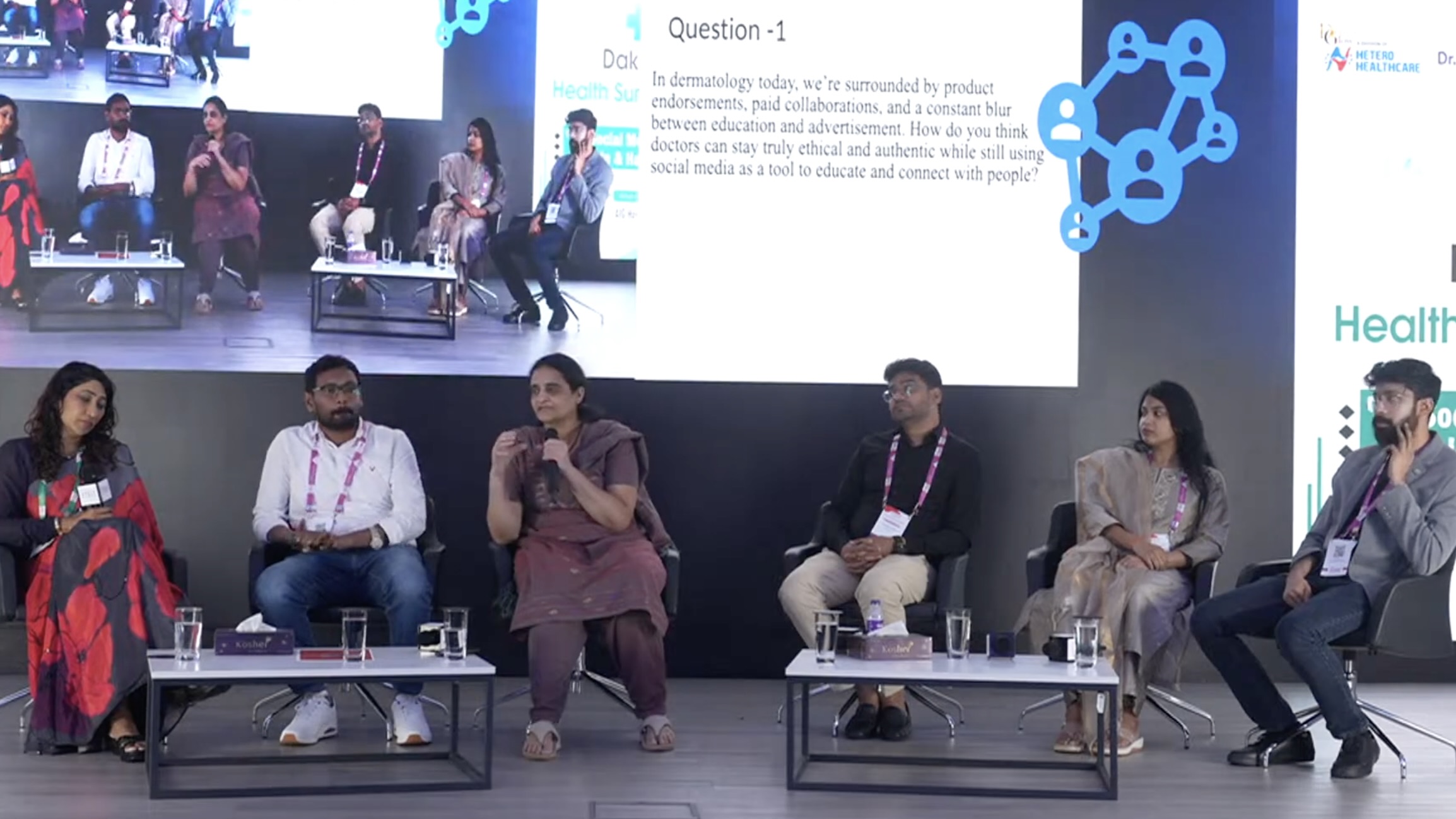

The second edition of the Dakshin Health Summit 2025 was held at the Asian Institute of Gastroenterology in Hyderabad on Sunday, 9 November.

At a time when hashtags such as “instant fairness”, “glass skin”, and “peel-at-home” are trending, experts warn that India is sleepwalking into a digital health disaster.

That warning came loud and clear during a recent discussion featuring a panel of experts at the second edition of South First’s Dakshin Health Summit, held at the Asian Institute of Gastroenterology (AIG), Gachibowli, Hyderabad, on Sunday, 9 November.

The experts included Dr K Sai Sandeepthi, dermatologist and moderator of the discussion; Dr Avinash Pravin, consultant dermatologist; Dr Jalagam Vijay, dermatologist and co-opted member of the Legal and Antiquackery Committee, TOMC; Dr Karishni Chittarvu, dermatologist and General Secretary, RDA Telangana; Dr Sivaranjani Santosh, senior paediatrician, first aid trainer and social activist; Dr Sangeet Kumar K, dermatologist; and Dr Rajetha Damisetty, senior dermatologist.

The panellists expressed alarm over digital quackery, unethical endorsements and the increasing number of patients reporting burns, scarring and kidney damage caused by unsafe products promoted on social media.

“If you want to be a 100 percent ethical doctor, you cannot endorse any brand or product on social media,” said Dr Sivaranjani Santosh, senior paediatrician.

For Dr Sivaranjani, the issue is not one of convenience but of credibility. She believes the medical profession’s trust deficit begins when doctors turn into influencers for commercial gain.

Her view is echoed by Dr Rajetha Damisetty, Chairperson of the IADVL Anti-Legal and Ethics Committee, who said the Code of Ethics for Medical Practitioners (2002) is crystal clear:

“No registered medical practitioner should endorse anything. What you or I think is immaterial – it’s what the law of the land says. If we want to change that, we must go to court, not Instagram.”

The Indian Association of Dermatologists, Venereologists and Leprologists (IADVL) has already issued social media etiquette guidelines for doctors, warning that any form of product endorsement—whether through direct posts, collaborations, or disguised testimonials—violates medical ethics and can invite disciplinary action.

Yet, Dr Damisetty admits that violations are rampant.

“Many doctors do not even realise they are breaching ethical lines when they appear in reels with brand tags or say ‘this works for my patients’. That is an endorsement, and it is prohibited,” she said.

In a world where skin health advice travels faster than fact checks, dermatologists are battling a new breed of misinformation merchants – unqualified “skin experts” with millions of followers offering treatments that range from dubious to dangerous.

“Social media has given doctors huge reach, but it has also created a serious problem – digital quackery,” said Dr Rajetha Damisetty.

Under India’s telemedicine guidelines, potent drugs such as isotretinoin, methotrexate and biologics cannot be prescribed during a first consultation.

However, several self-styled practitioners and “beauty doctors” openly flout these rules online, offering virtual prescriptions without examination.

Equally troubling are the step-by-step medical tutorials circulating on platforms such as Instagram and YouTube.

“Awareness is good,” Dr Damisetty cautioned. “But when doctors start showing every step of a chemical peel or microneedling online, it becomes a manual for quacks to copy and replicate.”

She calls this the “grey zone of good intentions”, where legitimate educational efforts accidentally empower untrained practitioners.

From toothpaste masks to homemade chemical peels, dermatologists say they are seeing a steady rise in patients suffering from burns and hyperpigmentation due to do-it-yourself skincare trends.

“DIY may work for your home, not for your skin,” said Dr Sangeet Kumar K.

Dr Avinash Pravin shared a recent case that highlights the risks.

“A patient applied an ‘onion peeling oil’ promoted by an influencer who claimed it made him fair. The oil contained 50 percent glycolic acid – he ended up with chemical burns.”

Dr Pravin also warned about the rampant sale of mercury-laden fairness creams such as Ghori and Tyza, which are still available in some Indian markets despite being banned.

“Mercury is a slow poison. It damages the kidneys and can cause foetal harm in pregnant women. Yet, it’s openly sold as a whitening solution.”

Such products, often marketed through informal online channels, have become a silent public health hazard.

While most doctors condemn unsafe beauty shortcuts, they also acknowledge the larger social and economic forces driving people towards them.

“When healthcare itself isn’t accessible, people will naturally choose cheap, quick fixes,” said Dr Sivaranjani Santosh.

She pointed out that dermatology services, especially cosmetic ones, remain out of reach for large sections of society.

“It’s not that people don’t care about safety. They just can’t afford private dermatology or wait endlessly in government hospitals.”

Dr Rajetha Damisetty added a crucial perspective.

“We talk from an urban, privileged lens – but real India is not this. I treated a nanny who found a skin cream on YouTube even though she can’t read. That’s how powerful vernacular social media is.”

She argued that the solution lies in using the same platforms to spread verified, affordable and language-accessible medical information.

“We need to flood social media with authentic dermatology in regional languages – that’s how we reclaim it from quacks,” she said.

“Social media creates unrealistic beauty standards – flawless, poreless, filter-perfect faces,” said Dr Karishni Chittarvu.

Dr Karishni, a young dermatologist representing the Gen Z perspective, believes that the constant exposure to filtered perfection is fuelling “Snapchat dysmorphia” – a condition where people want to look like their edited selfies.

She noted that while her generation is more skincare-conscious, it also battles anxiety and low self-esteem.

“The good news is that Gen Z is learning about sunscreen, actives and long-term care. But the downside is that they expect results overnight. That’s when they turn to dangerous quick fixes,” she added.

Several doctors in the discussion expressed concern over the growing number of patients who arrive with pre-diagnosed “conditions” after consuming large volumes of social media advice.

“Many patients now walk in and say, ‘Doctor, I have melasma because of this product’. They’ve already self-diagnosed through influencers. That’s when we start unlearning,” said Dr Avinash Pravin.

This overexposure to fragmented medical information has also led to what doctors call “paralysis by analysis”, where patients endlessly switch treatments or lose trust in legitimate medical advice.

According to Dr Jalagam Vijay, a member of the Anti-Quackery Committee, many doctors are unaware of the National Medical Commission (NMC) ethical framework for social media.

“Guidelines already exist – but enforcement is weak. We’ve suspended doctors for associating with quacks or claiming false specialisations. We need to take this digital misconduct as seriously as physical malpractice.”

He also emphasised that the NMC’s upcoming digital health code should explicitly address influencer collaborations, paid promotions and fake online reviews – areas currently operating in a legal limbo.

Despite the challenges, the doctors agreed that quitting social media is not an option.

“We need more ‘docfluencers’ – qualified doctors using social media responsibly to fight misinformation,” said Dr Rajetha Damisetty.

Many of them, however, admitted to facing online harassment, fake accounts and abuse for calling out unethical practices.

“You have to be thick-skinned,” said Dr Damisetty. “We’re not here to compete for likes. We’re here to protect patients.”

The consensus among the experts was clear: social media itself isn’t the enemy – misuse is.

“Unless we make ethical, evidence-based information accessible and affordable, unsafe shortcuts will keep filling the gap we leave empty,” said Dr Sivaranjani Santosh.

As India continues its digital health revolution, dermatologists warn that the country must urgently update its medical ethics framework for the influencer age – one where a viral reel can either save skin or destroy it.