Published Jun 08, 2025 | 7:00 AM ⚊ Updated Jun 08, 2025 | 7:00 AM

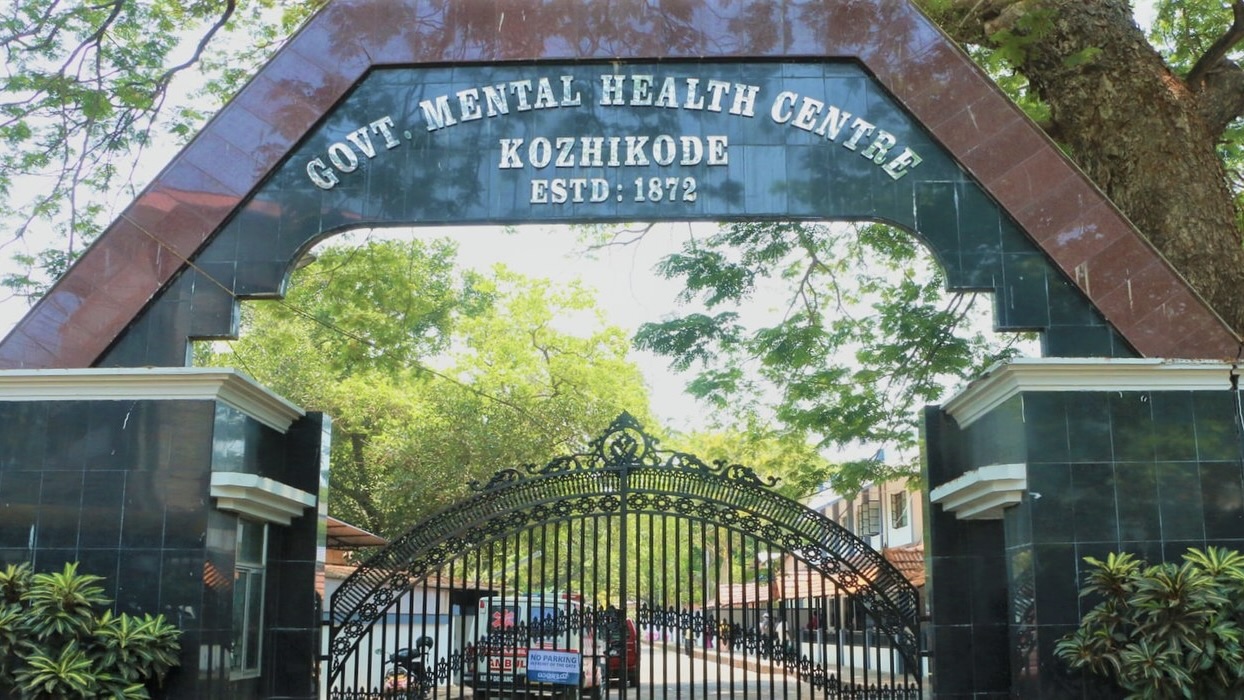

Government Mental Health Centre, Kozhikode

Synopsis: Kerala’s model healthcare system appears to be ill equipped to tackle a growing mental health crisis, with a suicide rate nearly double the national average and a mere 5.53 beds available per 10,000 people. The surge in mental illness is linked to post-pandemic trauma, family and financial stress, substance abuse, and a rapidly ageing population, with older adults and adolescents particularly vulnerable. Experts call for urgent systemic reforms, including workforce expansion, integration of mental healthcare into primary systems, community outreach, and culturally sensitive models of care.

Kerala, often upheld as a model for its achievements in public health, is now grappling with a mounting mental health crisis – one that its existing healthcare infrastructure is struggling to manage.

In 2018 data, Kerala had only 5.53 beds per 10,000 people seeking mental health treatment. Meanwhile, reported cases of depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders have risen steadily.

The growing burden is the result of several factors: the psychological aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, changing family structures, an ageing population, and mounting financial stress.

“At the district hospital, we are mainly dealing with follow-up cases from the mental hospitals, private hospitals, and private consultations,” said Dr T Sagar, Senior Consultant and Nodal Officer of the District Mental Health Programme (DMHP) in Pathanamthitta, speaking to South First.

He explained that a mobile unit – comprising a psychiatrist, clinical psychologist, psychiatric social worker, psychiatric nurse, and essential medicines – currently visits 23 selected clinics across the district. But he also flagged a critical shortage of trained personnel:

“The posts of psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, psychiatric social workers, and psychiatric nurses should be appointed in all district and taluk hospitals.”

Kerala remains an outlier in India for its disproportionately high mental health burden.

A 2021 paper titled The Burden of Mental Health Illnesses in Kerala: A Secondary Analysis of Reported Data from 2002 to 2018 found that the prevalence of mental illness and intellectual disability rose from 194 per 100,000 population in 2002 to 300 per 100,000 in 2018.

The number of individuals with mental health illnesses similarly increased from 272 per 100,000 in 2002 to 400 per 100,000 in 2018.

This shortfall is especially troubling, given that mental disorders account for the second-highest number of Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) worldwide.

A 2016 study by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) reported that approximately one in seven Indians lives with a mental disorder, with depression and anxiety affecting 45.7 million and 44.9 million people, respectively.

In Kerala, the National Mental Health Survey (2015–16) recorded an overall prevalence of mental disorders at 11.36 percent.

The most common conditions were depressive disorders (2.49 percent), neurotic and stress-related disorders (5.43 percent), and substance use disorders (4.82 percent).

The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) in 2014 reported a high risk of suicidality in 2.23 percent of Kerala’s population.

By 2018, the state’s suicide incidence rate had climbed to 23.5 per 100,000 persons – more than twice the national average.

Data from the Kerala Disability Census, 2015, revealed that 8.66 percent of households had at least one person with a disability, with 232 per 10,000 people affected by mental or physical disabilities.

Among the total disabled population (7,93,937), 12.72 percent had mental illness, 8.68 percent had intellectual disabilities, and 0.804 percent were diagnosed with cerebral palsy.

Severe mental disorders – such as schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder, and severe depression with psychotic features – were reported in 0.44 percent of the population.

Mental health problems were more prevalent among males (14.96 percent) than females (8.12 percent), largely due to the higher incidence of substance use disorders in men.

The 50–59 years age group showed the highest prevalence at 13.94 percent, likely due to increased rates of depressive and substance use disorders.

Dr Jini K Gopinath, Clinical Psychologist and Hypnotherapist based in Bengaluru, underscored the psychological distress faced by adolescents today.

“One in five students aged 12–19 is experiencing mental health challenges,” he said, attributing the situation to changing family structures, social isolation, economic pressures, and stress associated with migration.

He also flagged a growing concern: “Substance abuse among adolescents is an emerging crisis, with 15 percent consuming alcohol.”

“Kerala’s suicide rate is nearly double the national average, driven by family conflicts, financial distress, and untreated mental illness. The state’s mental health infrastructure is highly under-equipped, with only 5.53 mental health beds per 10,000 people,” Dr Jini added.

He noted that the COVID-19 pandemic had intensified the crisis by exposing long-standing systemic inadequacies.

“To address this, Kerala needs comprehensive mental health reform,” he said.

Dr Jini emphasised that strengthening services, integrating mental healthcare into primary health systems, expanding community outreach, and implementing school- and workplace-based mental health initiatives were all essential.

“Developing robust policies to address addiction, suicide prevention, and post-pandemic mental health care are also needed,” he said.

Senior PsychiatristDr CJ John, observed that “invasion of quality interaction time by electronic screen time has badly affected parenting time. This has compounding effect on harms done to life skills of the children. We have more children coming with mental health issues. We also need to have more innovative school-based initiatives.”

Dr John also highlighted the role of financial and social stressors.

“Lack of financial discipline, and mad consumerist culture has pushed a significant percentage of population to a culture of spending beyond resources,” he said.

He warned that such behaviours increase the risk of being caught in financial frauds.

“Mental health morbidities due to debt traps are on the increase. The state needs to have more awareness-building for a culture of living within resources,” he said.

“Human relationships are becoming shallow as time spent for mutual understanding is becoming lesser. Interpersonal respect is losing ground due to high egotistic attitudes. Divorces and relationship breakups are increasing.”

He called for a renewed focus on “life skills in the upbringing of the children.”

Dr CJ John pointed to another demographic at risk: the elderly.

Kerala’s rapidly ageing population – 13 percent of its citizens are already elderly, with projections pointing to a staggering 34 percent by 2051 – raises urgent questions about how prepared the state is to meet the complex mental health needs of its senior citizens.

“Migration of young persons from Kerala is leaving behind elders who are becoming susceptible to mental health issues. The state needs to have community mental health initiatives targeted at this population,” he said.

The rising burden of comorbidities, coupled with the social isolation of elders, demands a robust and adaptive health system. But are Kerala’s existing infrastructure and services equipped for this demographic shift?

According to Dr Sivakumar P Thangaraju, Professor and Head of the Geriatric Psychiatry Unit at NIMHANS, Bengaluru, Kerala holds the highest proportion of older adults in India.

“The life expectancy at birth is 75 years for males and nearly 80 years for females. An older adult aged 60 years in Kerala is expected to live more than 20 years.”

“These demographic changes have contributed to the increase in prevalence of mental health problems in older adults, like dementia and depression,” he said.

“The number of older adults aged 60 years and above with dementia is estimated to increase from 4,14,000 in 2016 to 6,96,000 in 2036.”

Dr Sivakumar pointed to broader social shifts that are aggravating the issue.

“The increase in the old age dependency ratio and the migration of younger people within India and abroad have contributed to the challenges in the support system for older adults with mental health problems,” he noted.

He warned that the rise in the population aged 80 and above will further complicate care.

“There will be high rates of medical comorbidities and frailty along with mental health problems. The existing support systems are not adequate. We need to develop culturally appropriate and sustainable care models that are suitable for our context.”

He added that a majority of the elderly live in rural areas, with an increasing number of them living alone.

“There is a need to implement community-based interventions to address loneliness, promote healthy lifestyles, and prevent mental health problems,” he said.

“We must develop both community- and institution-based rehabilitation services, particularly for those from low socio-economic backgrounds. Home-based mental health services integrated with general healthcare are essential, and we also need to promote age-friendly communities.”

A 62-year-old patient from Kozhikode who has been on medication for depression for the past three years, shared his experience.

“Earlier, I used to face work-related problems. Due to anxiety, I was not able to do my job properly, and I began to lose my grip over my responsibilities. However, after a course of medication, things are getting back to normal,” he said.

“In the beginning, I had certain doubts. Though I have not fully recovered from the deprivations, I can discharge my functions regularly with the support of medication.”

Dr Sudhir Kumar, honorary consultant at the Alzheimer’s and Related Disorders Society of India (ARDSI), Kottayam, explained the overlap between depression and dementia.

“Depression can be a symptom of dementia. However, from a public health point of view, depression is a well-established modifiable risk factor for dementia. People with depression in mid-life are at a higher risk of developing dementia later in life. By diagnosing and adequately treating depression, the effect of this risk factor can be reduced,” he said.

“The reason for this is not clearly understood. There are biological explanations postulated. Some other reasons considered include that when depressed people do not look after themselves and have poor social contact – both of which increase the risk of developing dementia,” he added.

Dr Sudhir also pointed to other mental health conditions.

“Sleep difficulties, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and post-traumatic stress disorder have also been shown to increase the risk of dementia, though we are still awaiting stronger evidence,” he added.

He noted that degenerative dementias, being incurable, place a heavy burden on families.

“Risk reduction strategies can effectively reduce the number of people affected by dementia. Awareness programmes and public health campaigns can go a long way in achieving this,” he said.

“Kerala government initiatives like Ormathoni are laudable in addressing dementia care. But we need more concerted action involving both governmental and non-governmental agencies to meet this challenge.”

Dr Sairu Philip, Principal of Kannur Medical College Hospital and a well-known expert in community medicine, acknowledged that the state government had already launched a range of initiatives to tackle the growing crisis.

“Already the government through the health services and government departments have rolled out programs to promote mental health, prevent illness, and ensure treatment,” she said.

For instance, the District Mental Health Programme, ‘Ammamanasu’, on-call lines for suicide prevention, school counsellors among others.

“But the main gap is stigma towards identifying and treating even common mental health problems like depression,” she observed.

Dr Philip noted that mental health promotion must be age-inclusive, spanning “children, adolescents, youth, midlife and the elderly.”

She highlighted Kerala’s decentralised planning in health as a unique opportunity.

“Panchayats can formulate their own projects to promote mental health. Eg: Muhamma Panchayat has its own specific project from planned fund to care for mental illness and palliative care for them. Here, psychiatrist from an NGO conducts regular clinic in panchayat and undertakes home care visit with the help of trained volunteers,” she explained.

“Another unique program floated out by the Panchayat is ‘Home Again’ – a rehabilitation home for those who have completed treatment but are not accepted at home,” she added.

According to Dr Philip, identifying common mental health issues such as depression and anxiety should be a part of everyday practice for all medical professionals.

“It should be known and incorporated into their daily practice by every MBBS or MD doctor irrespective of specialty,” she suggested.

“The importance of mental health, though known, is not internalised when it comes to treating a person with specific system illness. Naturally, all those social determinants can affect mental health by impinging on access to mental health service and affordability,” she said.

However, she also cautioned that the comforts of modern life could create their own vulnerabilities.

“It is a two-edged sword. Complete comfort and receiving everything from childhood may result in impatience and lack of resilience to adversities, resulting in mental health issues,” she said.

“Also, to those vulnerable to mental ill health, these social determinants may be the ones that can tilt the balance.”

(Edited by Dese Gowda)