Published Dec 16, 2025 | 3:00 PM ⚊ Updated Dec 16, 2025 | 3:00 PM

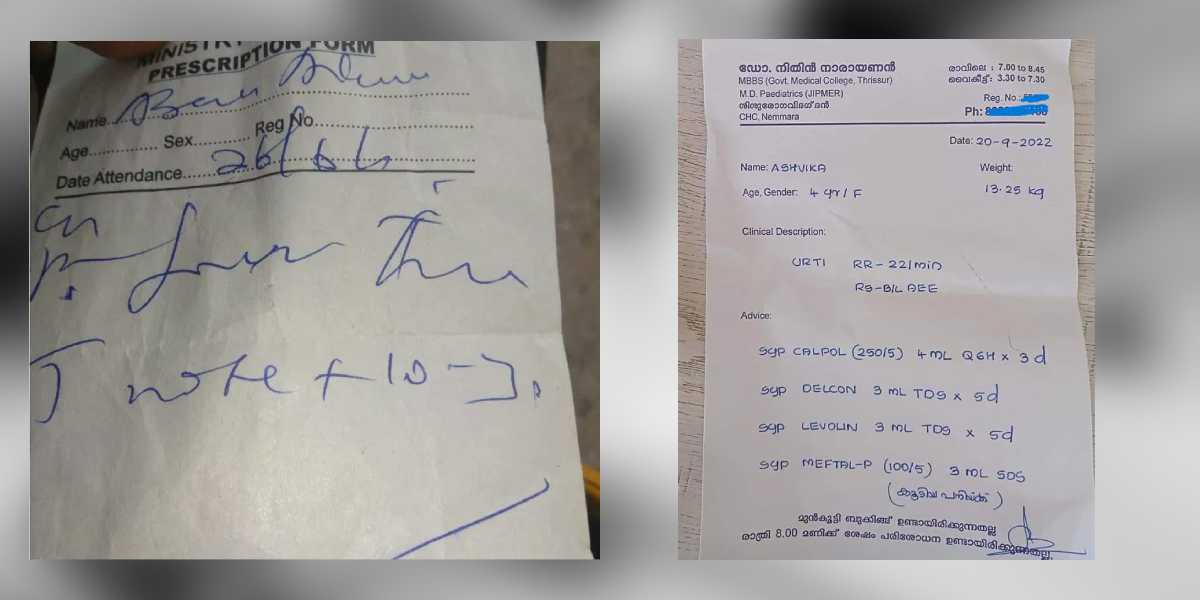

When pharmacists cannot read a prescription, they must contact the doctor for clarification, which delays the start of treatment.

Synopsis: The National Medical Commission has ordered all medical colleges to form sub-committees to monitor prescription practices and enforce legible handwriting, following a High Court directive linking clear prescriptions to the right to health. The move aims to curb medication errors, improve patient safety, ensure regulatory compliance, and address negligence driven by workload, poor oversight, and clinic–pharmacy nexuses.

The National Medical Commission (NMC) has issued a directive to all medical colleges and institutions across India, mandating the immediate formation of sub-committees aimed at rigorously monitoring prescription practices and reinforcing the crucial role of clear handwriting in medical documentation.

The instruction, formalised on 15 December 2025, follows a public notice issued by the Post Graduate Medical Education Board (PGMEB) dated 11 December 2025. This measure is a direct consequence of an order issued on 27 August 2025 by the High Court of Punjab and Haryana in the matter of Yogesh vs State of Haryana.

The High Court required the NMC to ensure the importance of legible and clear handwriting is included and reinforced within the curriculum of all medical colleges. Furthermore, the court emphasised the constitutional implications of clear medical records, noting that “a legible medical prescription/document is an essential component of the right to health under Article 21 of the Constitution of India”.

NMC affirmed the necessity of strengthened oversight, stating that the “National Medical Commission has observed the need for strengthened and structured monitoring of prescription practices across all medical colleges in accordance with the regulations currently in force”.

To enhance adherence to existing statutory, regulatory, and ethical standards, every medical college is now required to establish a dedicated sub-committee under its existing Drugs and Therapeutics Committee (DTC).

These sub-committees are tasked with developing a structured plan for the systematic appraisal of prescriptions to assess compliance with applicable regulations. Their duties include reviewing and analysing prescription patterns, identifying deviations, and recommending corrective measures. The institutions must ensure that the findings of each appraisal are recorded in the minutes of the DTC meetings and made available to the NMC when requested. They must also ensure “timely implementation of all recommended measures to enhance compliance of the court order”.

Medical institutions were also reminded of prevailing regulations that dictate the standard for prescription writing. The NMC public notice reiterates the mandatory nature of these directions: “Every physician should prescribe drugs with generic names legibly and preferably in capital letters, and he/she shall ensure rational prescription and use of drugs”.

All institutions have been instructed to constitute the sub-committee immediately and to “operationalise the prescribed monitoring mechanisms without delay”. The notice was formally issued by Raghav Langer, secretary of the NMC.

Dr Sudhir Kumar, a neurologist at Hyderabad-based Apollo Hospital, outlined the serious consequences that stem from scribbled prescriptions.

“There are several types of mistakes that can occur in prescriptions, which can have serious consequences for patients,” he explained.

“Medication errors are among the most dangerous; the wrong drug, incorrect dose, or improper route of administration may be prescribed. For example, abbreviations like OD (once daily) or BD (twice daily) are often misread, leading to patients taking medicine incorrectly,” Dr Kumar told South First.

The ripple effects extend far beyond simple confusion. When pharmacists cannot read a prescription, they must contact the doctor for clarification, which delays the start of treatment. Incorrect drugs or doses can cause side effects or allergic reactions, while patients may not receive the intended benefits, defeating the purpose of prescribing medicine in the first place.

The financial burden is equally significant. “Mistakes can lead to extra consultations, hospital visits, or treatments for side effects, increasing the financial burden on patients,” Dr Kumar said. Perhaps most concerning is the impact on patient compliance: “Patients who do not understand their prescriptions may skip doses or stop treatment altogether, losing trust in the doctor and the healthcare system.”

The legal implications are also serious. “If a prescription error causes harm, the patient has the right to take legal action, placing liability on the doctor. Whilst the patient suffers most of the harm, the onus of responsibility rests with the prescribing physician,” Dr Kumar warned.

Every medical student in India is formally taught how to write a prescription as part of the pharmacology course, usually in their second year before they even enter clinical postings. So, if every doctor graduating in this country has been taught the skill and yet many prescriptions remain illegible, the question is why it’s not being practised.

“One major issue is linked to small clinics and nursing homes. Many nursing homes have their own pharmacies, and the prescriptions are written in such a way that only their pharmacist can understand the prescription and dispense the medication. Similarly, in small clinics, some doctors write in a manner that ties patients to a particular pharmacist, with the doctor often getting a cut from the sale. For example, a medicine costing ₹500 may give a doctor a ₹50 commission,” Hyderabad based pulmonologist Dr M Rajiv highlighted.

Dr Rajiv also highlighted the overwhelming patient loads that many doctors face daily. “The practical reality is that doctors in busy clinics see hundreds of patients a day. Writing a neat prescription in block letters takes more time than scribbling quickly, and so it gets skipped.”

This workload issue is particularly acute in government facilities. “It’s a failing public health system that lies at the root of this entire issue. If you walk into a corporate or large private hospital, you’ll almost never see a scribbled prescription. Why? Because each doctor in their outpatient departments handle maybe 20–30 patients at a time. The problem of illegible prescriptions emerges mostly in government facilities and low-level private setups,” Dr Rajiv said.

The human resource crisis is at the heart of the problem. “At its core, the problem is human resource scarcity. Whether it’s violence against doctors, lack of empathy in healthcare, or poor quality of care—it all stems from the fact that we simply don’t have enough competent doctors, nurses, or allied health workers. Expecting a doctor to see 400 patients a day is unrealistic.”

Dr Rajiv said that legible prescription writing is not a new concept and is already taught during medical training, but the real issue lies in non-compliance.

“The fastest thing doctors need to do is know the rules,” he said, adding that lack of clarity in prescriptions often points to two distinct problems. “If someone is unqualified, they don’t even know the spellings. In qualified doctors, illegible writing is plain negligence.”

Referring to existing regulations, he stressed that prescription clarity is not optional. “According to NMC guidelines and professional misconduct rules, prescriptions must be written clearly and legibly, preferably in capital letters,” he said, echoing the regulatory mandate that “every physician should prescribe drugs with generic names legibly and preferably in capital letters, and ensure rational prescription and use of drugs.”

Dr Rajiv pointed out that multiple laws converge on this issue. Under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, medicines cannot be dispensed without a valid prescription. The Pharmacy Act, 1948, reinforces the same principle, whilst clinical establishment rules prohibit issuing prescriptions without proper registration.

His core message, he said, was simple: “Every doctor must write prescriptions clearly, with their name and registration number. These are mandatory. If they are missing, a complaint can be made directly to the Medical Council or the DMHO—whether the person is qualified or not.”

He explained that clear prescriptions serve multiple purposes: preventing dispensing errors, helping future doctors understand prior treatment, and enabling comparison with earlier prescriptions. “It benefits the patient first, then the next doctor, and even the same doctor later,” he said.

Clear handwriting, he added, also helps identify quackery. “Unqualified people don’t know spellings. That itself becomes a differentiating factor,” he said, arguing that this transparency can help restrain the drug mafia. “If pharmacies dispense medicines only against proper prescriptions, misuse automatically reduces.”

Addressing concerns that clear writing increases patient waiting time, Dr Rajiv said the argument does not hold. “E-prescriptions are already being used. More importantly, rules mandate proper patient examination. Seeing more patients is not mandatory—seeing patients properly is.”

The real problem, according to him, lies in smaller towns and villages where clinics and pharmacies often operate together. “Pharmacies run nursing homes and nursing homes run pharmacies. That nexus is dangerous for the public,” he warned.

In contrast, he said corporate hospitals usually maintain clear documentation because doctors value their registration numbers earned after years of struggle.

“If even a small percentage of offenders are stopped, the rest of the system corrects itself,” he said. Patients, he added, have the right to complain if a prescription is illegible or lacks a registration number.

“People must know whether they are being treated by a qualified doctor or not. That is why the Medical Council and the NMC exist.”

(Edited by Amit Vasudev)