Published Jan 24, 2025 | 3:57 PM ⚊ Updated Jan 24, 2025 | 3:57 PM

Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister N Chandrababu Naidu’s proposal to bar candidates with less than two children from contesting local elections has sparked critical conversations about the delicate balance between demographic management, reproductive rights, and social equity.

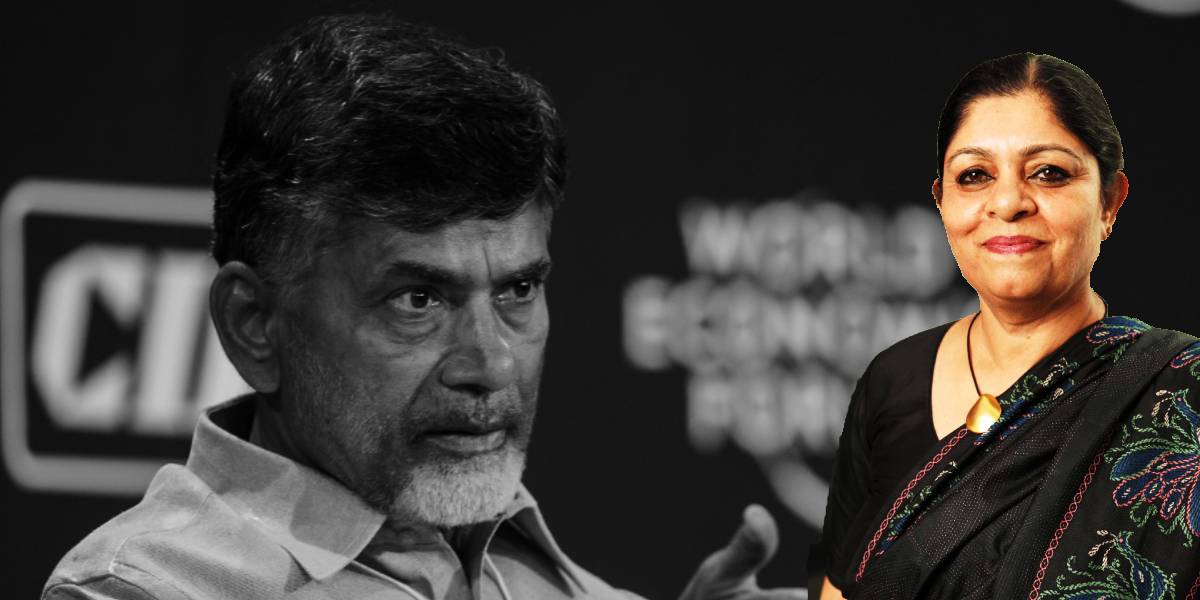

Following the remarks, South First spoke to Population Foundation of India Executive Director Poonam Muttreja to understand her perspective regarding population control and related policies.

With over four decades of experience advocating for women’s health and rights, Muttreja’s work has been pivotal in promoting gender equity, reproductive health, and population stabilisation through a rights-based approach.

She provided a nuanced analysis of India’s challenges and opportunities as it charts its demographic future.

Q: Many people are curious about the repercussions of state leaders’ statements, including the one by Naidu. Do we need to focus on increasing our population? Does a larger population contribute to economic growth?

A: Andhra Pradesh should take pride in its remarkable achievement of reducing fertility rates to 1.7, below the replacement level. This success reflects years of progress in women’s empowerment, family planning, healthcare, and governance.

Lower fertility has empowered women and addressed unwanted fertility, aligning with India’s demographic goals. Andhra Pradesh has been a leader in population stabilisation, outperforming many other states.

The focus should remain on empowering and educating women. When women thrive, fertility stabilises naturally, and the state can confidently build on its success.

Q: There seems to be an economic angle to this debate. Leaders often argue that a larger population can lead to more workforce participation and, ultimately, economic growth. Is this the right approach, or is it simply a political concern?

A: If Andhra Pradesh had enough jobs, its youth wouldn’t migrate to other states or countries like the US. Most would prefer to stay if opportunities were available. However, there’s a shortage of both jobs and skilled workers.

Instead of focusing on population issues, the state should invest in education, skill development, and job creation to retain talent. Targeted investments in technology and skills training will create “pull factors” that will prepare youth for a workforce increasingly reliant on technological expertise.

Migration within India is inevitable due to overpopulation in states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, but effective migration policies can balance labour supply across regions. Political concerns, especially delimitation, must be addressed without hindering long-term development.

Q: I’ll come to delimitation later, but first, I’d like to focus on the recent statement by Chandrababu Naidu. He has proposed barring candidates with fewer than two children from contesting local body elections. Given the traumatic history of forced sterilisation in India, do you think this is the right approach?

A: I’m surprised by Mr Naidu’s statement, given his reputation as a visionary leader. This proposal is misguided — It is ethically questionable. Moreover, global evidence shows it doesn’t work in practice.

Countries like Japan and South Korea, despite efforts to boost birth rates, have struggled with stagnant or declining populations. Simply “pushing” women to have more children doesn’t work.

Women are not switches that can be turned on and off.

Women in Andhra Pradesh, and across India, already want fewer children, reflecting their aspirations for education, better jobs, and later marriages. Mr. Naidu seems out of touch with these aspirations. What women need are supportive policies — education, job opportunities, childcare, and parental leave — like those in Sweden and Norway, which have achieved stable population growth by empowering women and families.

Andhra Pradesh has made commendable progress in women’s education and empowerment, leading South India’s more progressive approach. The chief minister should build on this success, not propose regressive policies like the two-child norm, which has failed before.

12 Indian states implemented it for Panchayat elections, leading to harmful outcomes: Divorce on paper, children given up for adoption, and discrimination against women and the poor, as revealed by studies like Nirmala Buch’s. Why target marginalised Panchayat candidates while sparing MLAs and MPs, why not include the MPs and MLAs? This selective application is inequitable and unjust.

Forced sterilisation policies during the Emergency era showed the dangers of such regressive measures. Instead of repeating past mistakes, policymakers should focus on empowering women, reducing poverty, and creating growth opportunities.

Q: There is a concern about the ageing population in the Southern states since fertility rates have been below the replacement level. How can governments effectively prepare for the challenges posed by this demographic shift?

A: Preparing for an ageing population is vital, and Kerala offers valuable lessons, even though there’s much to improve. Countries like Japan also provide insights into tackling this challenge.

While India, including Andhra Pradesh, still enjoys a demographic dividend with a young population, now is the time to plan for an ageing society.

One way is to meaningfully engage older individuals without raising the retirement age. For example, expanding opportunities in caregiving can address a growing need while creating jobs.

Social security is another priority. Governments must ensure robust safety nets, including pensions and affordable healthcare. At the same time, investing in young people’s health today can reduce future medical costs by addressing non-communicable diseases early and strengthening health systems.

Planning and advocacy are key. States like Andhra Pradesh should push for fair fiscal allocations from the Union government to address ageing challenges, especially since lower fertility rates shouldn’t lead to reduced funding.

With its history of strong governance and health investments, Andhra Pradesh can become a model for managing an ageing population while preparing its younger generations for the future. This approach can inspire other states and countries to navigate similar demographic shifts.

Q: As you mentioned, southern states may face reduced influence and funding with upcoming delimitation, but increasing fertility to address workforce shortages primarily burdens women. Women bear children, often step away from jobs, and face career setbacks. Is the state taking women for granted?

A: The state’s approach not only takes women for granted but also violates their reproductive rights. Tying policies to increased fertility unfairly burdens women while ignoring workforce issues.

Women already shoulder immense responsibilities in a society lacking affordable childcare and eldercare. Forcing them to choose between aspirations and population goals is regressive.

Workforce shortages in Andhra Pradesh can be addressed through skilling, not pressuring women. With strong universities and infrastructure, the state can fill gaps in sectors like healthcare and teaching.

Penalising women, who often lack autonomy in marriage and childbearing, is unjust. Mr Naidu should engage with women’s collectives on this issue. Women today seek fewer children, meaningful careers, and autonomy — aspirations the state must support.

To ease caregiving burdens, the state could incentivise men to share responsibilities, taking cues from Norway’s Masculinity Commission. Men often want working women but fail to support the infrastructure they need. Policymakers should respect women’s agency and dignity, not force traditional roles on them.

Q: Why does the state want to control women’s bodies and their social roles?

A: It is completely unacceptable for any government to enter the bedrooms or houses of the people. There is enough for you to do outside the bedroom, then enter their bedroom. This level of intrusion into a woman’s autonomy, particularly when it comes to reproductive choices, is both regressive and counterproductive.

Moreover, from a political perspective, it’s a strategy doomed to fail. Why would you set yourself up for failure? Women are increasingly part of the workforce, contributing to the economy and society in significant ways. Any attempt to impose additional burdens on them will only alienate them and hamper their progress.

Q: At a time when women are striving to participate in the workforce and the state is progressing, there seems to be a disconnect between the state’s vision and the aspirations of its people, especially women. How can the state align its policies with the population’s needs and expectations?

A: The Union government’s role is crucial here. Delimitation is tied to the South’s political insecurities, including in Andhra Pradesh. The South fears losing representation if delimitation is based solely on population. However, representation should consider developmental achievements, fiscal needs, and national contributions.

Andhra Pradesh should champion alternative approaches to delimitation, prioritising equity over population numbers. As an ally of the Union government, Mr Naidu can advocate for such reforms. Instead of focusing on divisive issues like controlling women’s reproductive rights, he should present data-driven, merit-based arguments for fair representation.

Postponing delimitation to allow demographic parity, as done previously, is another option. Penalising the South for its progress while states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar lag is unjust.

Delimitation must not punish achievement, and any process that does should face opposition. Postponing it until parity is achieved is a pragmatic solution. Restricting women’s reproductive rights is morally wrong and impractical. The state should focus on empowering policies that respect women’s autonomy.

Q: Since childhood, I’ve heard the slogan “Hum Do Humare Do” (Two of us, two of ours), which promotes voluntary family planning. However, the current approach seems coercive. What is the ideal solution for managing population growth and family planning?

A: Families have always made their own decisions about children, and the idea that slogans like “Hum Do Humare Do” drove these choices is a myth. High child mortality in the past led to larger families, but with better healthcare, child survival rates improved, naturally reducing family sizes. Education, especially for women, accelerated this shift. Globally, educated women typically have fewer children.

Economic pressures, like rising living costs, are further lowering fertility rates. Government rations can’t fix this; addressing food inflation, creating jobs, and improving quality of life will.

To become a developed country, we need more than economic targets — better education, healthcare, and economic security will empower families to make voluntary decisions about family size. With an average fertility rate of 1.8, India’s future growth will be by choice, not coercion.

Southern states like Andhra Pradesh achieved low fertility through voluntary family planning, accessible contraception, and high female literacy — not coercion. We can learn from Denmark and Germany, where policies like affordable childcare and equal parental leave promote sustainable growth. Coercive policies are politically disastrous, as history shows. Empowerment, not enforcement, is key.

Q: India faces a regional disparity: The South has an ageing population, while the North has a much younger demographic. How can the country address this gap to achieve economic growth and tackle the challenges of regional and fertility disparities?

A: There are two key areas we need to focus on.

In the South:

In the North:

The North doesn’t need to look to South Korea or Japan — it can learn from Southern states, which have excelled in governance, education, and healthcare.

Instead of penalising the South for its success, the Union government should reward high-performing states like Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. Penalising them only unfairly burdens women.

Collaboration is key: The South can leverage its healthcare and industries, while the North contributes a youthful workforce. A balanced, united approach will harness the strengths of both regions for national progress.

(Edited by Muhammed Fazil.)