Published Dec 27, 2025 | 3:09 PM ⚊ Updated Dec 28, 2025 | 12:09 PM

Asian Tiger Mosquito, one of the most dangerous invasive species, is known for being a primary vector for diseases such as dengue and chikungunya. Credit: iStock

Synopsis: India’s 2023 dengue death toll shows a 571% discrepancy: 3,254 deaths recorded by the Registrar General versus 485 by NCVBDC. State-level gaps highlight systemic failures in surveillance, with Delhi, Karnataka, and West Bengal showing extreme differences. The mismatch undermines case fatality rates, exposing flaws in reporting, weak private sector compliance, and risks of underestimating dengue’s true lethality.

India’s official dengue death toll for 2023 varies by a staggering 571 percent depending on which government agency is reporting the numbers, with the Registrar General of India recording 3,254 dengue deaths while the National Centre for Vector Borne Diseases Control (NCVBDC) under the health ministry reported only 485 deaths for the same year.

The 571 percent gap between the two official datasets has exposed critical flaws in India’s disease surveillance and death reporting systems, raising urgent questions about the accuracy of public health data used for policy planning and resource allocation.

The Report on Medical Certification of Cause of Death 2023, released by the Office of the Registrar General of India, documented 3,254 medically certified dengue deaths (1,840 males and 1,414 females) based on death certificates issued by medical practitioners across the country. In contrast, the NCVBDC’s surveillance data reported 485 dengue deaths from 2,89,235 reported cases, suggesting a case fatality rate of 0.17 percent.

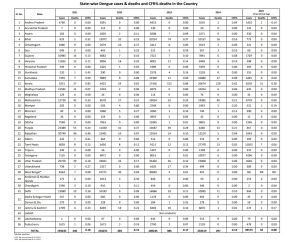

Official dengue deaths by health ministry.

Perhaps the most striking anomaly appears in Andhra Pradesh, where the NCVBDC surveillance system reported zero dengue deaths from 6,453 reported cases, yet medical death certificates documented 90 dengue deaths (35 males and 55 females) in the state.

This suggests either a complete breakdown in reporting dengue deaths to the surveillance system or fundamental problems in linking clinical diagnoses with official disease monitoring.

Chhattisgarh reported zero dengue deaths in NCVBDC data from 2,412 cases, yet medical certificates recorded 34 deaths. Madhya Pradesh shows a similar pattern with zero surveillance deaths from 6,979 cases, but 17 medically certified deaths.

Chandigarh recorded 117 medically certified dengue deaths but reported zero deaths in NCVBDC surveillance from 454 cases. Bihar shows 39 medically certified deaths against 74 in surveillance data, one of the few states where surveillance numbers exceed certification.

Kerala presents an unusual reverse pattern. The state recorded 153 dengue deaths in NCVBDC surveillance data from 17,426 reported cases (a 0.88 percent case fatality rate, the highest in India), but medical certification records show only 40 dengue deaths (23 males and 17 females).

This three-fold difference in the opposite direction suggests Kerala’s active surveillance system may be capturing deaths that are not being reflected in the formal medical certification process, possibly due to deaths occurring outside hospitals or classification differences in cause-of-death reporting.

Karnataka reported 243 medically certified dengue deaths but only 11 in NCVBDC data from 19,300 cases, a 22-fold difference. Tamil Nadu shows 94 medically certified deaths against 12 in surveillance data from 9,121 cases, nearly an eight-fold gap.

West Bengal recorded 100 medically certified dengue deaths but only 4 deaths in NCVBDC surveillance from 30,683 reported cases, a staggering 2,400 percent difference. This represents one of the largest proportional gaps in the country.

Punjab shows 87 medically certified deaths against 39 in surveillance data from 13,687 cases. Rajasthan recorded 145 medically certified deaths but only 14 in surveillance data from 13,924 cases, more than a 10-fold difference.

Gujarat reported 137 medically certified dengue deaths against 7 in NCVBDC data from 7,722 cases, a 19-fold gap. Odisha shows 90 medically certified deaths but only 1 surveillance death from 12,845 cases, a 90-fold difference.

The discrepancy reaches alarming proportions in individual states. Delhi recorded 538 dengue deaths according to medical certification data, but the NCVBDC surveillance system reported only 19 deaths from 16,866 cases in the Capital, a difference of 2,736 percent.

Maharashtra shows a 9-fold gap, with 487 medically certified dengue deaths against 55 deaths in NCVBDC data from 19,034 reported cases. Haryana recorded 285 deaths in medical certification records but only 11 in surveillance data, a 25-fold difference.

Uttarakhand reported 255 medically certified dengue deaths but only 17 in NCVBDC surveillance, a 15-fold gap. Uttar Pradesh shows 277 medically certified deaths against 36 in surveillance data, nearly an 8-fold difference.

The gap indicates that a significant proportion of dengue deaths occur outside the surveillance net, either in private hospitals that do not report to the surveillance system, in smaller healthcare facilities, or are recorded post-mortem without being fed back into active disease monitoring.

Across southern states, medical certification consistently exceeds surveillance reporting. The region recorded 557 medically certified dengue deaths (294 males and 263 females) but NCVBDC surveillance captured only 180 deaths.

Karnataka leads southern states with 243 medically certified deaths (134 males and 109 females), representing 43.6 percent of the region’s dengue mortality. Telangana shows 79 medically certified deaths against just 1 in surveillance data, while Andhra Pradesh’s 90 certified deaths appear nowhere in surveillance records.

Tamil Nadu recorded 94 medically certified deaths (49 males and 45 females) against 12 surveillance deaths, while Puducherry shows 11 certified deaths against 2 in surveillance data.

Medical certification data reveals dengue kills more men than women, with males accounting for 56.5 percent (1,840) of total dengue deaths and females 43.5 percent (1,414). This pattern holds across most states, though some show exceptions.

Notably, Andhra Pradesh recorded more female dengue deaths (55) than male deaths (35), one of the few states showing this reversal. The gender disparity in dengue mortality may reflect differences in healthcare-seeking behaviour, occupational exposure, or biological susceptibility.

Delhi leads the country in medically certified dengue deaths at 538 (16.5 percent of national total), followed by Maharashtra at 487 (15 percent), Haryana at 285 (8.8 percent), Uttar Pradesh at 277 (8.5 percent), and Uttarakhand at 255 (7.8 percent).

These five states account for 1,842 deaths, representing 56.6 percent of all medically certified dengue mortality in India. However, their combined surveillance deaths total only 137, capturing just 7.4 percent of certified deaths.

The massive gap between the two systems renders published case fatality rates largely meaningless for public health planning. The NCVBDC’s national CFR of 0.17 percent is based on 485 deaths from 289,235 cases. However, if the actual death toll is 3,254 as medical certification suggests, the true CFR would be 1.13 percent, nearly seven times higher.

This has profound implications for epidemic preparedness, as health authorities may be significantly underestimating the lethality of dengue outbreaks and consequently under-allocating resources for case management and critical care.

The discrepancy highlights fundamental structural problems in India’s health information systems. Medical certification of deaths falls under the civil registration system managed by the Registrar General, while disease surveillance operates under the health ministry’s NCVBDC with separate reporting mechanisms.

The two systems do not communicate effectively, resulting in parallel datasets that should match but diverge by hundreds of percentage points. Deaths certified by doctors as dengue-related are not being systematically reported to the disease surveillance system, breaking the feedback loop essential for epidemic monitoring and response.

Private sector reporting remains particularly weak, with private hospitals and clinics often failing to notify dengue deaths to surveillance authorities despite legal requirements under the Epidemic Diseases Act. The medical certification system captures these deaths because death certificates are mandatory for legal purposes, but the information does not flow to public health authorities.

(Edited by Amit Vasudev)