Published Nov 18, 2025 | 3:12 PM ⚊ Updated Nov 18, 2025 | 4:26 PM

AI-generated image for representational purpose.

Synopsis: AIG Hospitals study in Lancet reveals 83% of Indian ERCP patients already carry multidrug-resistant bacteria—highest globally—vs 31% Italy, 20% US, 10% Netherlands. Over-the-counter antibiotics, incomplete courses, and self-medication fuel a community-level superbug crisis. Without urgent prescription enforcement and stewardship, routine infections and procedures risk becoming deadly and unaffordable.

When doctors at AIG Hospitals in Hyderabad placed their endoscopy tools under microscopes after cleaning, they discovered something that made them pause: bacteria that simply refuse to die, no matter how thoroughly the instruments are sterilised.

But the real shock came when they tested the patients themselves before any procedure began.

The findings revealed that 83 percent of Indian patients walking into the hospital already carried drug-resistant bacteria in their bodies, making India the epicentre of what researchers are now calling a superbug explosion.

The study, published in Lancet eClinicalMedicine during World Antimicrobial Stewardship Week, compared rates across four countries and found India’s numbers towering above the rest.

The procedure in question, called ERCP, involves threading a thin, flexible camera through a patient’s mouth into their stomach to diagnose and treat problems in the pancreas, liver, and gallbladder.

Millions of bacteria naturally live in the human digestive system, and some inevitably cling to these instruments during procedures.

Hospitals follow rigorous cleaning protocols between patients, sterilising every surface, but some bacteria have learned to survive. These survivors are what scientists call superbugs, organisms that have evolved to resist the very medicines designed to kill them.

The international study examined 1,244 procedures involving 1,154 patients across hospitals in India, Italy, the United States, and the Netherlands.

Each person underwent testing before their procedure to determine whether they were already carrying multidrug-resistant organisms. The results painted a troubling picture of geographical disparity in antibiotic resistance.

In India, 83 percent of the 349 patients tested carried resistant bacteria, with 70.2 percent harbouring organisms that produce enzymes capable of breaking down common antibiotics, and another 23.5 percent carrying bacteria that resist even the most powerful last-resort medicines.

By comparison, Italy recorded 31.5 percent, the United States showed 20.1 percent, and the Netherlands reported just 10.8 percent of patients carrying these organisms.

Dr D. Nageshwar Reddy, Chairman of AIG Hospitals and co-author of the study, didn’t mince words about what these numbers mean. “This study should ring the loudest alarm bell India has heard on antibiotic resistance,” he said.

“When over 80 percent of patients coming for a routine, commonly performed procedure are already carrying drug-resistant bacteria, it means the threat is no longer limited to hospitals—it is in our communities, our environment, and our daily lives.”

What makes these findings particularly concerning is that the difference cannot be explained away by medical history or the severity of illness. Even after researchers adjusted their analysis to account for factors like age, existing health conditions, and known risk factors.

India’s rates remained dramatically higher than other countries. This points to something more systemic, a problem that has seeped into communities rather than being confined to hospitals.

The study identifies several culprits: antibiotics are readily available over the counter without prescriptions, despite official regulations; patients routinely stop treatment courses midway through when they start feeling better; and self-medication with leftover antibiotics from previous illnesses remains commonplace.

“The widespread availability of antibiotics without prescription likely contributes to the high prevalence of MDRO in India,” the research notes, highlighting how this has become a public health emergency that extends far beyond clinical settings into everyday life.

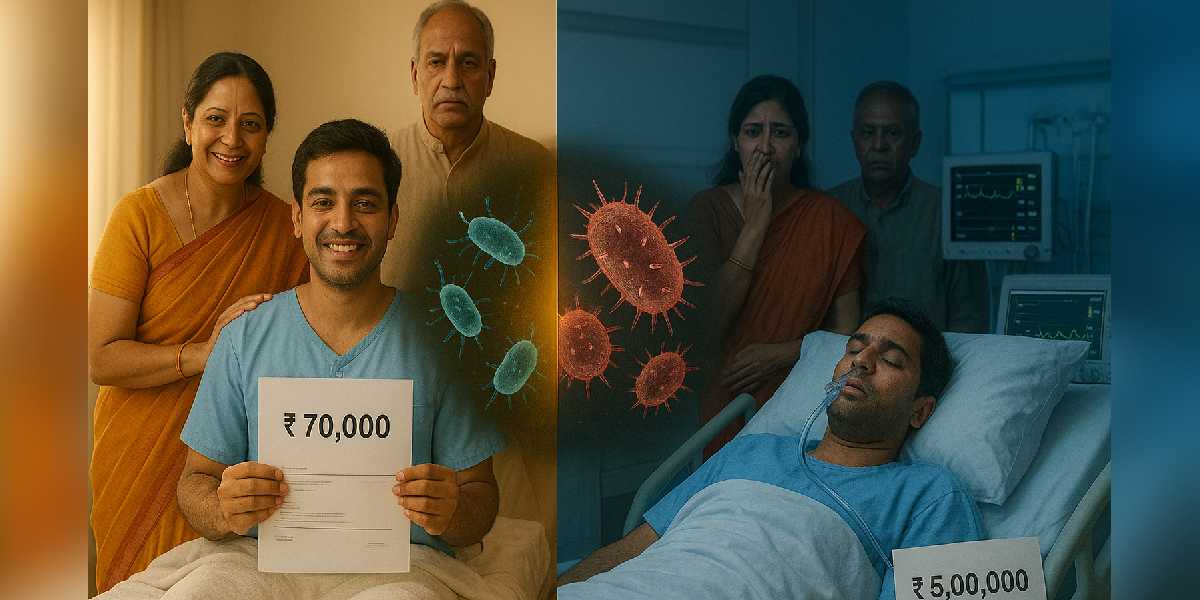

Dr Reddy shared a story that brings the abstract statistics into sharp focus, illustrating the real-world impact of carrying drug-resistant bacteria. Two patients arrived at the hospital with identical diagnoses of acute cholangitis, both requiring the same ERCP procedure, but their journeys through treatment couldn’t have been more different.

The first patient, who tested negative for drug-resistant bacteria, responded quickly to standard antibiotics, stabilised within 48 hours, was discharged after three days, and walked out with a bill of roughly Rs 70,000. The second patient, carrying multidrug-resistant organisms, became a completely different story.

First-line antibiotics failed to work, forcing doctors to escalate to more powerful and toxic drugs. The infection worsened into sepsis, demanding intensive care unit admission. The hospital stay stretched beyond 15 days, and the final bill climbed to between Rs 4 and 5 lakh—nearly seven times higher than the first patient.

Dr Hardik Rughwani, a gastroenterologist and co-investigator at AIG Hospitals, emphasised how this scenario plays out repeatedly. “The levels of multidrug-resistant bacteria we observed in India are deeply concerning,” he said.

“These organisms delay recovery, increase complications, and significantly raise treatment costs. Doctors are forced to rely on stronger and more toxic antibiotics, and patients end up staying longer in hospitals.”

The process of bacterial resistance follows a ruthless logic of natural selection. When someone takes antibiotics for a viral cold—which antibiotics cannot treat—the bacteria living harmlessly in their body are exposed to the medicine anyway. Most die, but a few with random genetic variations survive.

These survivors multiply, passing their resistance traits to their offspring. Each time this happens, the bacterial population becomes slightly more resistant.

India faces particular challenges that accelerate this process. Pharmacies frequently sell antibiotics without requiring prescriptions, despite regulations. People share leftover pills with family members.

Patients feel better halfway through a course and decide to stop taking the medicine. Each incomplete treatment course becomes a training ground for bacteria to develop resistance.

The consequences are already visible: India records approximately 58,000 newborn deaths annually linked to resistant infections, and hospitals routinely encounter bacteria that no available antibiotic can treat.

When standard antibiotics fail, the entire treatment paradigm shifts. Doctors must prescribe more powerful drugs that carry heavier side effects, potentially damaging kidneys and livers.

Hospital stays extend from days to weeks. Recovery becomes slower and more painful. Surgical procedures that were once routine become high-risk endeavours, because even a minor post-operative infection could turn deadly if caused by resistant bacteria.

The financial burden multiplies alongside the medical complications. Families exhaust savings on extended hospital stays and expensive medications.

The healthcare system strains under the weight of patients requiring intensive care for infections that should have been easily treatable. Dr Rughwani’s observations reflect this pressure: “If we do not address this crisis now, our healthcare system will be pushed to the brink.”

The publication in the Lancet family of journals carries significant weight. These publications maintain some of the strictest peer review processes in medical science, and their findings are trusted by researchers and policymakers worldwide.

The timing of the study’s release during World Antimicrobial Stewardship Week, which runs from November 18 to 25, amplifies its message when global health agencies are already focused on promoting responsible antibiotic use.

The researchers followed rigorous protocols, collecting throat and rectal swabs from each patient, culturing these samples in laboratories, and identifying six different types of resistant organisms.

They acknowledged several limitations: all participating hospitals were tertiary care centres treating more complex cases, which might inflate resistance rates; India’s centre performed up to 50 procedures daily, exceeding laboratory capacity and potentially introducing selection bias; and the patient population in India differed substantially from other sites in terms of demographics and procedure indications.

Dr Reddy outlined six actions that individuals can take immediately, steps that could collectively slow the spread of antibiotic resistance if practiced widely enough.

First, never take antibiotics without a doctor’s prescription—no self-medication, no pharmacy suggestions, no leftover pills from previous illnesses. This single behaviour change could dramatically slow resistance development.

Second, stop demanding antibiotics for viral illnesses, because most fevers, colds, coughs, and sore throats are caused by viruses that antibiotics cannot touch.

Third, when antibiotics are prescribed, complete the full course even after feeling better, because stopping midway allows surviving bacteria to multiply and develop stronger resistance.

Fourth, maintain strong hygiene practices including regular handwashing, drinking clean water, and safe food handling, because preventing infections means needing fewer antibiotics in the first place.

Fifth, keep vaccinations up to date, as vaccines prevent infections entirely and eliminate the need for antibiotic treatment.

Sixth, handle pets and livestock responsibly by never administering antibiotics without veterinary guidance, because resistant bacteria readily transfer between animals and humans.

Beyond individual actions, the researchers are calling for sweeping policy changes. They want antibiotics sold exclusively by prescription, with enforcement mechanisms that actually work. They’re proposing nationwide antibiotic stewardship programmes that monitor and guide appropriate use across all healthcare settings.

They suggest implementing digital tracking systems for antibiotic prescriptions and sales. They demand stronger regulation of pharmacies, with real consequences for violations. They urge mass public awareness campaigns that reach rural and urban populations alike.

The approach must be comprehensive, addressing what scientists call a “One Health” strategy that recognises how antibiotic use in humans, livestock, agriculture, and sanitation systems are all interconnected.

Farmers give antibiotics to animals to promote growth. Agricultural operations apply them to crops. Inadequate sanitation spreads resistant bacteria through water systems. Each of these pathways feeds into the others, creating a complex web that requires coordinated intervention across multiple sectors.

Dr Reddy issued a stark warning about what lies ahead if India doesn’t act decisively.

“We are staring at a future where simple infections may become untreatable,” he said. “India urgently needs a national movement on antibiotic stewardship, public education, and strong regulatory action to prevent a true public health disaster.”

The data positions India at a critical juncture. Common infections that doctors have treated easily for decades could become killers.

Routine surgeries might carry new and unpredictable risks. Everyday medical procedures could threaten lives in ways they haven’t for generations. The country must choose its response now, because the biological clock of bacterial evolution doesn’t wait for convenient political moments or budget cycles.

This study, built on rigorous international collaboration and published in one of the world’s most respected medical journals, provides the evidence that policymakers need. The question is no longer whether India has a crisis on its hands—the numbers make that undeniable.

The question is whether the response will match the scale and urgency of the threat before the window for effective action closes.

(Edited by Amit Vasudev)