Published Feb 22, 2026 | 5:45 PM ⚊ Updated Feb 22, 2026 | 5:45 PM

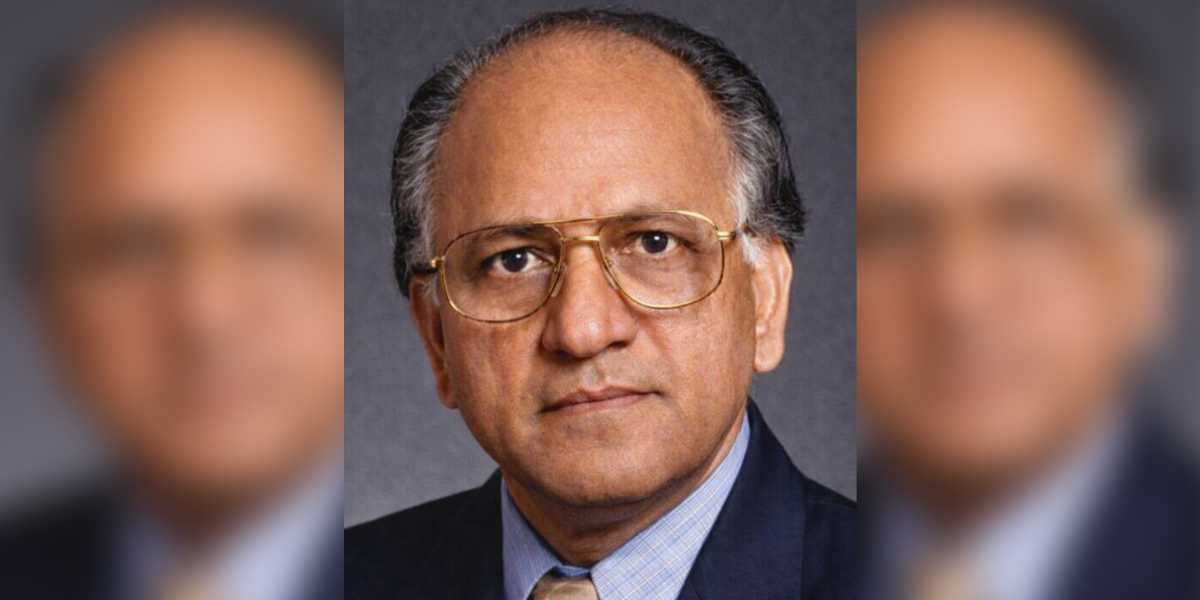

Seshagiri Rao Mallampati

Synopsis: Dr Seshagiri Rao Mallampati, who died at 85 in the US, transformed anaesthesiology with his pioneering Mallampati Score. Inspired by a failed intubation case, he devised a simple mouth-and-tongue test predicting airway difficulty, now a global standard ensuring safer surgeries across operating theatres worldwide.

Dr Seshagiri Rao Mallampati built his life’s work on a single, nagging question that refused to leave him alone: why do some patients become impossible to intubate, even when everything looks perfectly normal from the outside?

He died on 9 February, 2026, in the United States. He was 85.

He was born in 1941 in Patchalatadi Parru, a small settlement in Andhra Pradesh. He walked through the gates of Guntur Medical College in 1963, transferred to Andhra Medical College in Visakhapatnam in 1965, and graduated with his MBBS in 1968.

He honed his skills at King George Hospital before emigrating to the US in 1971, part of a generation of Indian doctors who crossed oceans in search of operating theatres, equipment and possibilities that India had not yet built for them.

By 1975, he had completed his residency in anaesthesiology at the Lahey Clinic Foundation and Boston Hospital for Women, followed by a clinical fellowship at Harvard Medical School. He earned his Diplomate of the American Board of Anaesthesiology in 1976, his Fellowship a year later, and settled into the rhythms of attending anaesthesiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

#Airway

So sad to hear the news of Dr Seshagiri Rao Mallampati !

An airway legend from Telugu states in 🇮🇳 well known internationally for airway #mallampati classification!!

🕉️🙏🕉️@ASALifeline @AoraIndia @Siva6faces @Ropivacaine @BrighamWomens @ISANHQ @kajal_pgi pic.twitter.com/CdybiCPyKr— 🩺 Hari (హరి 🇮🇳) Kalagara (@KalagaraHari) February 21, 2026

At some point during his career, a patient arrived in his operating theatre and did something that the textbooks had not prepared anyone for. The patient’s head and neck looked anatomically normal.

The positioning was correct. The equipment was in order. And yet, when Mallampati attempted to pass a tube down the patient’s trachea — the standard procedure that allows a machine to breathe for someone under general anaesthesia — he could not do it.

He investigated. What he found was this: the base of the patient’s tongue had grown disproportionately large relative to the space at the back of the throat. That excess tongue was sitting like a curtain drawn across a stage, hiding the uvula — that small teardrop of tissue dangling at the back of your mouth — and the faucial pillars, which are the two arches of tissue framing either side of your throat.

The trachea was buried behind all of it. Invisible. Unreachable. The throat as a doorway, and what happens when furniture blocks it

Picture your throat as a corridor. At the end of the corridor sits a door, that door is your trachea, the airway that leads to your lungs. An anaesthesiologist, during intubation, needs to see that door clearly enough to pass a tube through it.

Now imagine someone has shoved a large sofa, the base of the tongue — into the entrance of that corridor. The sofa does not block the door completely, but it blocks your line of sight to it. The larger the sofa, the less you can see. If it is large enough, it pushes forward and narrows the angle to the door, making the whole manoeuvre something between difficult and impossible.

Mallampati understood that the sofa’s size announced itself before the patient ever entered an operating theatre. You could see it, simply by asking the patient to open their mouth and stick out their tongue.

From that moment, Mallampati made it a habit. Every patient. Open your mouth. Stick out your tongue. Let me see whether your uvula and faucial pillars are visible, or whether that tongue has swallowed them from view.

He gathered data. He published a letter to the editor of the Canadian Anaesthetists Society Journal in 1983, signalling that he had found something worth paying attention to. Two years later, in 1985, by then an Assistant Professor of Anaesthesiology at Harvard Medical School, he published his landmark study in the same journal, drawing on 210 patients.

The study divided patients into three classes. Class one: the surgeon can see the faucial pillars, the soft palate and the uvula, the corridor is wide open. Class two: the soft palate and part of the uvula remain visible, but the pillars have disappeared. Class three: only the soft palate is visible. The sofa fills the corridor. Intubation, the study confirmed, grows substantially more hazardous as you move from class one to class three.

In 1987, two British doctors, Dr Samsoon and Dr Young, published a revision in the Journal of Anaesthesia, adding a fourth class to account for cases where even the soft palate disappears entirely. The four-class Mallampati Score has remained the standard ever since.

What a 30-second test does for a patient who does not yet know they need it

An anaesthesiologist running a Mallampati assessment spends less than thirty seconds on it. The patient sits upright, opens their mouth as wide as it will go, extends their tongue, and breathes normally. No instruments. No machines. No radiation.

What that thirty seconds does is hand the surgical team a map of the difficulty ahead. A class three or four patient triggers a different set of preparations: different equipment staged and ready, more experienced hands in the room, a plan and a backup plan. The patient lies on the table unaware that a test conducted in a pre-operative room has already changed the architecture of their surgery.

From Visakhapatnam to every operating theatre on earth

Mallampati retired from medical practice in 2017, having spent over four decades in American operating theatres. His score travels without him, used in nursing homes in Hyderabad, in teaching hospitals in London, in surgical centres in Houston and Tokyo and Nairobi.