Published Nov 19, 2025 | 8:00 AM ⚊ Updated Nov 19, 2025 | 9:43 AM

AI in healthcare. (Supplied)

Synopsis: The report raised questions that asked for insights from India’s healthcare system. Has AI truly arrived in our hospitals? Can machines read medical scans reliably? Should patients trust them with their lives? The answer sits somewhere between promise and caution.

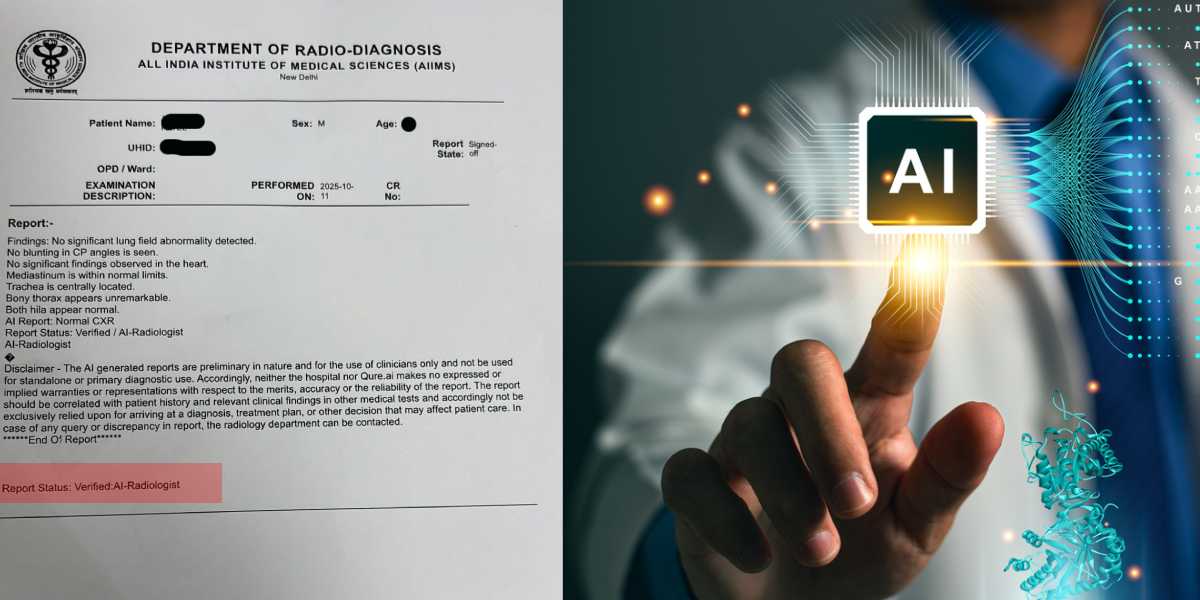

A chest X-ray report landed on social media last week with an unusual header: “Verified/AI-Radiologist.”

The report was from All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, and stated the patient’s chest X-ray was normal. However, at the bottom, a disclaimer warned that the findings were “preliminary,” generated by Qure.ai’s system, and could not be used for diagnosis alone.

Dr Sumer Sethi, a radiologist and founder of DAMS α , shared the image and called it “a big leap for medical tech and a great workflow booster: faster reads, fewer misses, better triage.”

But he added a crucial caution: “AI outputs are preliminary and must be clinically correlated. Radiologists interpret context, complexity, and patient nuance.”

AI wrote an X-ray report at AIIMS — but here’s the real story. My thoughts on the viral report on social media today.

It’s a big leap for medical tech and a great workflow booster: faster reads, fewer misses, better triage. But the viral report itself reminds us — AI outputs are… pic.twitter.com/ma5K6kSrpA

— Dr Sumer Sethi (@sumersethi) November 13, 2025

The report raised questions that asked for insights from India’s healthcare system. Has AI truly arrived in our hospitals? Can machines read medical scans reliably? Should patients trust them with their lives?

The answer sits somewhere between promise and caution.

Richard Roy Mendonce heads brand, digital, and PR at Gleneagles Hospitals India, part of IHH Healthcare Singapore. Having worked across five major hospital brands and watched AI enter the clinical space, he clarified that he is not a medical expert and the opinions are based on his personal observations and interest in AI.

“Healthcare has been one of the early adopters of AI,” he explained to South First. “It first evolved through character recognition, image recognition, and voice recognition and then advanced into identifying patterns in data, especially medical imagery.”

The chest X-ray became the testing ground because hospitals perform these scans more than any other imaging procedure. The image looks deceptively simple: two lungs, some ribs, a heart shadow. But inside that grayscale frame, soft tissue hides complexity that can mean the difference between life and death.

“You need a certain level of skill to differentiate whether it is pneumonia, fibrosis, or a smaller abnormality,” Richard explained. “This means there can be false positives and false negatives, even with skilled radiologists, especially when the volume of scans increases and the chances of human error go up.”

AI stepped in with an advantage humans cannot match: it has accessed enormous datasets and learned from lakhs of X-rays showing both disease and health. “If it identifies pneumonia, it does so after having ‘seen’ lakhs and lakhs of X-rays with and without pneumonia,” Richard said. “It can quickly flag an image saying, ‘This probably looks like pneumonia.'”

The machine works at a pace that seems almost supernatural. An AI model can process large batches of X-rays in minutes, generate preliminary assessments, and have everything ready for the radiologist to review.

If everything looks accurate, the system can even generate a pre-drafted report that the doctor can verify, sign, and release. This saves time that doctors desperately need when faced with mounting patient loads.

The radiologist can filter cases strategically. Some teams choose to see AI-flagged positives and critical alerts first, then review a sample of AI-negative cases to catch any false negatives. The goal is to reduce the chance of missed disease while still speeding up the list.

Mammography followed the same pattern of AI adoption, and here the technology found an even more critical role. Women queue for these scans in screening programmes across the country. Large calcifications show up clearly on mammograms, and radiologists spot them without difficulty.

But microcalcifications remain extraordinarily difficult to detect. These tiny changes in breast tissue can mark very early breast cancer and are hard to detect with the naked eye unless someone is highly experienced.

“From my experience and from one of the projects I worked on, the more challenging part, even for trained radiologists, is identifying microcalcifications,” Richard said. “These are very early, tiny changes in breast tissue that are hard to detect with the naked eye unless someone is highly experienced.”

AI picks them up because it analyses patterns at a level of detail that exceeds human visual processing. It catches what radiologists miss, potentially saving lives through earlier detection. “This means earlier detection, faster screening, and strong support in settings where there is a heavy workload and a shortage of radiologists,” Richard said.

Consider another scenario: a whole-body MRI generates more than a hundred image views for a single patient. The radiologist must scroll through each slice of the scan, mentally reconstructing the three-dimensional anatomy and identifying abnormalities. Then they write a detailed report, a process that drains hours from their day.

AI watches alongside the radiologist, picking up findings and pre-drafting sections of the report as the doctor reviews images.

The doctor dictates changes or makes minor edits while reviewing, and the machine updates the report automatically, transforming it into a well-crafted, proof-checked, clinically evaluated document. “This improves patient safety, saves time, and enhances accuracy,” Richard said.

What makes AI work in healthcare? Radiologists train it, teach it, and correct it in an ongoing cycle of improvement. “AI is essentially a machine-learning model,” Richard explained. “It learns what you teach it, and radiologists have played an important role throughout this entire journey.”

The model starts completely naive, getting most diagnoses wrong in its early iterations. But every time radiologists and clinical experts give feedback, the model improves, refining its understanding of what separates disease from health.

Over the past years, the results have shifted dramatically from crude approximations to radiologist-level accuracy for many well-defined tasks.

“Experts say that what we are seeing now is at its worst AI will ever be it will only get better,” Richard said.

Many centres and large number of radiologists across the country now proofread AI-generated reports, and the model learns from their corrections, identifying where it commonly makes mistakes and what areas get frequently misinterpreted. “This whole system requires a strong human interface to be built in,” Richard added.

The tool unlocks clinical complexity that was previously accessible only to a handful of experts worldwide. Tasks that only elite specialists could perform have now become available to regular clinicians with AI support, allowing them to contribute to training models, develop new skills, and improve diagnostic accuracy across the healthcare system.

He further added, “Medtronic has partnered with AI companies such as Qure.ai to deploy stroke detection tools that plug into CT workflows in hub and spoke networks. In stroke, time is critical. Many programmes aim to complete imaging and make a treatment decision within about 60 minutes of arrival, because IV thrombolysis is usually given within 4–6 hours of symptom onset and benefit drops every minute.”

Picture a district hospital in a tier-two city where a patient arrives with stroke symptoms. A CT scan runs immediately, but no interventional neuroradiologist works at the facility because such specialists remain scarce in India.

The AI model analyses the scan feed in real time during the imaging process and immediately flags a probable stroke along with key findings. Expert radiologists trained this model over thousands of cases, and because it’s software, it can deploy simultaneously across hundreds of hospitals.

Once the scan completes, the AI-generated preliminary findings reach a radiologist’s phone, someone sitting in a major city perhaps hundreds of kilometres away.

They review quickly, confirm the diagnosis, and send back instructions: “This looks like a stroke. Please bring the patient in immediately.” The patient gets transported to a facility with the right expertise,

Hospitals are healthcare organisations, not technology companies, and even when they want to invest in developing technology, they usually lack the bandwidth to build complex systems from scratch. They cannot afford to spend millions hiring large engineering teams to develop proprietary technology.

So they adopt AI through collaboration and partnership. Apollo Hospitals partnered with Microsoft to work on AI models together. Manipal Hospitals worked with IBM to launch Watson for cancer diagnostics early in the AI revolution.

These partnerships work because IT firms need clinical data and medical expertise, while healthcare organisations need technological capability and engineering knowledge. The collaboration fills gaps on both sides.

Some hospitals simply subscribe to ready-made AI models from specialised companies, much like they subscribe to Microsoft Office rather than building their own word processor. Companies like Qure.ai provide solutions that hospitals can integrate into existing workflows without building anything themselves.

A few elite institutions Mayo Clinic, AIIMS, and a handful of top centres, might be developing their own models through specialised internal research projects. With many open-source AI models now available, even smaller institutions can start building their own tools.

The only limiting factor becomes data: do they have enough clean, structured medical data to train an effective model?

Apollo Hospitals demonstrates what’s possible with scale and long-term vision. They collected patient data over 10 to 15 years, building a dataset that now spans millions of patients. Every year they publish The Health of the Nation report, and because their data pool is so large and diverse, they can make predictions that sometimes exceed even state-sponsored research in scale and accuracy.

Couple of years ago, Apollo rolled out the Clinical Intelligence Engine, an AI-based clinical decision support tool built on this longitudinal patient data. Apollo says it is available free to every qualified practicing doctor in India.

Now a doctor sitting in a small town in a tier-two city can simply enter patient symptoms, and the tool will ask follow-up questions in natural language and guide the diagnostic process, bringing expert-level clinical reasoning to places where specialists rarely visit.

Startups take another path forward. Richard witnessed this model while working at one of the hospitals. “We were trying to help a tech startup that worked in radiology and imaging. They were from Gujarat,” he recalled.

Since they were a startup without access to clinical data, they partnered with multiple hospitals under a simple agreement: hospitals would provide anonymised data with no patient-identifiable information, and in return, the startup would give the hospital the final solution at nominal cost or even free for a certain period.

Both sides won—the tech company got the data it desperately needed, and hospitals got early access to cutting-edge technology along with the ability to test it and give feedback.

Government programmes offer startups access to large public datasets, and teams there can collaborate with large private hospitals to build combined datasets for AI development.

The third pillar of the AI data ecosystem involves using AI to create data itself through a process called synthetic data generation. AI models need balanced datasets to train effectively. If you want to train a chest X-ray model to detect pneumonia, the model needs roughly equal numbers of pneumonia cases and normal chest X-rays.

However, Real-world datasets are rarely balanced. For some tasks, there are many more normal X-rays than pneumonia cases. For rare conditions, there may be only a small number of positive examples. Synthetic data helps fill these gaps by generating realistic additional samples for whichever class is underrepresented.

Data scientists identify a small set of X-rays and then instruct AI to generate many more realistic X-rays that look similar. This expanded synthetic dataset helps balance the training material.

“Synthetic data is also used in hypothetical scenarios: when you want to build a model for a future condition or a rare disease, but there isn’t enough real-world data available yet, you can synthesise the dataset and train the model on it,” Richard explained.

Hospitals use AI far beyond clinical diagnosis, deploying it throughout their operations to speed up administrative processes and improve patient experience. Discharge summaries are now generated automatically, and insurance documentation that once took hours is now completed in minutes.

Today’s insurance documentation has become extraordinarily detailed and stringent. Every time a patient’s claim needs submission, a staff member must draft the entire summary in the exact format required by each insurance TPA, because every insurer demands different templates.

This manual work creates delays, and patients often wait hours for discharge even after they’re medically cleared to leave.

With AI handling these tasks, the system already knows the required format for each insurer. Once the doctor enters the discharge summary and instructions, the AI automatically generates the appropriate document and sends it forward, significantly reducing delays and improving the patient experience at a critical moment in their hospital journey.

Some hospitals now use AI for operational tasks like porter management. Porters are the staff responsible for moving patients in wheelchairs or stretchers from one floor to another, to diagnostics, or to surgery.

Traditionally, hospitals assigned porters to each floor or kept them in a common area, but this led to inefficiency—they sat idle during slow periods and got overwhelmed when patient movement suddenly increased.

Some hospitals now use AI-driven task assignment for porters. When a ward raises a request, the system identifies the nearest available porter and sends details to their phone, cutting delays and idle time. “These may seem like small use cases, but collectively they bring major improvements—better efficiency, smoother operations, and a significantly enhanced patient experience,” Richard said.

Drug safety systems powered by AI can access a database of every patient’s documented allergies, drug-resistant infections, and adverse reactions from previous treatments.

The system can immediately flag deviations and it dramatically improves patient safety at relatively low cost and potentially saves lives through preventing medication errors that might otherwise slip through in busy hospital environments.

Healthcare moves more slowly than retail, finance, or entertainment when adopting new technology, and for good reason: the stakes reach incomparably higher when lives hang in the balance.

“Hospitals are cautious about using AI on patients. They generally look for strong clinical validation, regulatory clearance, and stable performance before deploying these tools widely in routine care,” Richard emphasised. “Other industries have been able to adopt AI much faster because their risks are lower.”

The AIIMS report that went viral carried a prominent disclaimer stating that findings were preliminary, warning against standalone diagnosis, and requiring clinical correlation with patient history and other medical tests.

The disclaimer read: “Accordingly, neither the hospital nor Qure.ai makes no expressed or implied warranties or representations with respect to the merits, accuracy or reliability of the report.”

Dr Sethi framed the situation perfectly in his social media post: “The future is AI assisting radiologists, not replacing them.”

The machine reads the scan, identifies patterns, drafts preliminary findings, and speeds up workflow. But the human radiologist interprets context, weighs complexity, considers the patient’s unique situation, and makes the final diagnostic call.

That balance between machine efficiency and human judgement will define the next phase of healthcare in India. The AI has arrived in our hospitals, reading our X-rays and analysing our scans.

But it arrives not as a replacement for doctors, but as a tool that makes them faster, more accurate, and more available to patients who need their expertise. The machine signs the preliminary report. The doctor signs off on your care. And that distinction, for now and the foreseeable future, remains absolutely critical.

(Edited by Sumavarsha)