Published Aug 31, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Aug 31, 2025 | 9:00 AM

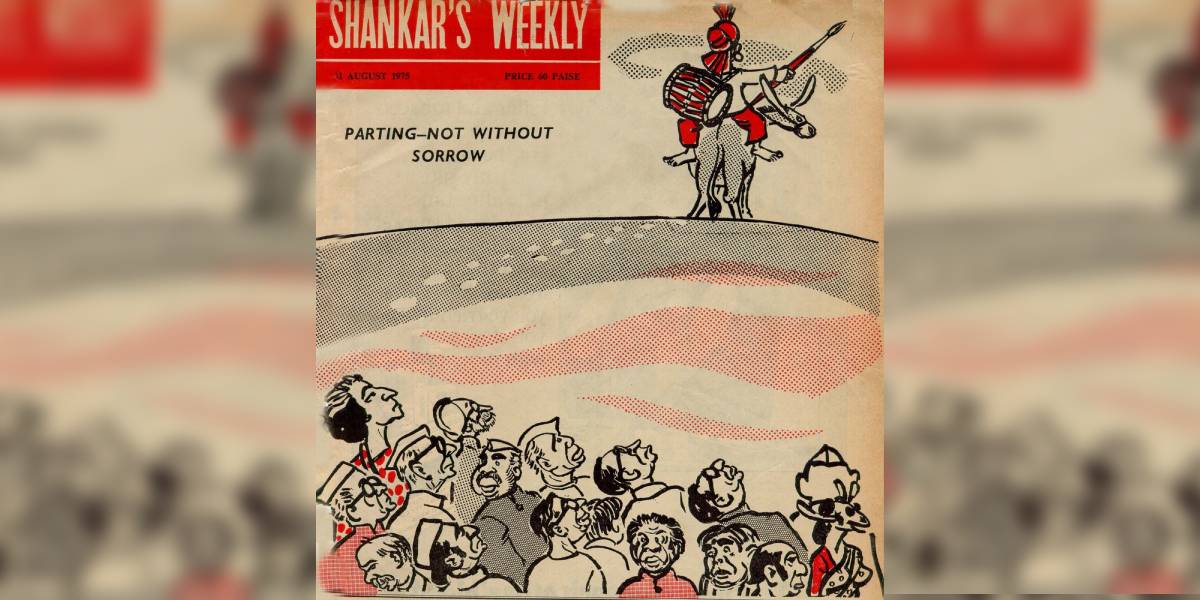

Shankar disagreed with Shakespeare's ‘Parting is such sweet sorrow.’ The cover of Shankar's Weekly last edition dated 31 August 1975.

Synopsis: Sunday, 31 August 2025, marks fifty years since ‘Shankar’s Weekly’ closed its shutters. Modelled on the British Punch, it quickly acquired a distinct Indian voice. Nehru inaugurated the magazine, though he was often lampooned in its pages. For nearly three decades, Shankar’s Weekly was irreverent, fearless, and free of party lines. Shankar described it as “fundamentally anti-establishment, while never toeing any particular line.”

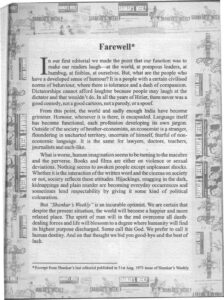

“Dictatorships cannot afford laughter,” wrote cartoonist Shankar (K. Shankar Pillai) in the final editorial of Shankar’s Weekly published on 31 August 1975, two months after an internal Emergency was clamped on India.

“In all the years of Hitler, there never was a good comedy, not a good cartoon, not a parody, or a spoof. From this point, the world and, sadly enough, India have become grimmer,” the editorial said.

Half a century later, his words still feel prophetic. In today’s world, where satire often stands under suspicion, the closure of Shankar’s Weekly reminds us how fragile such spaces always were. Its end was not forced censorship but Shankar’s own decision, an acknowledgement that the conditions for fearless humour were fast disappearing in India.

The Weekly’s passing marked not just the end of a publication but the retreat of laughter from public life.

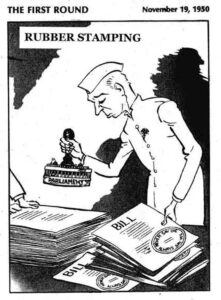

For nearly three decades, from its launch in 1948 to its closure in 1975, the magazine became India’s most important experiment in political humour. In an age when cartoons unsettled governments and delighted readers alike, Shankar’s Weekly offered a stage where satire spoke freely, and where words and drawings together captured the mood of a young democracy.

Shankar was born in Kayamkulam, Kerala, on 31 July 1902. Cartooning was first a pastime, but his sharp eye for politics soon found its place in journalism.

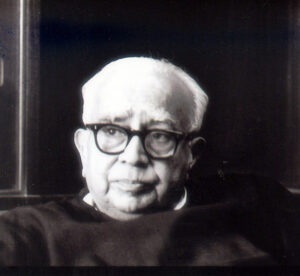

K Shankar Pillai

(31 July 1902 – 26 December 1989).

Pothan Joseph, the legendary editor of Hindustan Times, spotted his drawings and hired him as staff cartoonist. Shankar remained there until 1946, producing images that came to define a nation finding its voice.

In 1939, Mahatma Gandhi wrote to him after a series of cartoons on Jinnah. His advice was as stern as it was insightful: “Your cartoons are good as works of art. But if they do not speak accurately and cannot joke without offending, you will not rise high in your profession. Above all, you should never be vulgar. Your ridicule should never bite.”

Shankar carried this counsel throughout his career: the ability to lampoon without malice. His protégé Kutty later recalled Gandhi’s other remark, made after Shankar left Hindustan Times: “Did Hindustan Times make you famous, or did you make Hindustan Times famous?”

Silence was Shankar’s answer, for it was he who had given the paper much of its reputation, though he left the place following a disagreement with the management in 1946.

Historian Ritu Khanduri, in the publication Caricaturing Culture in India, noted that Shankar’s cartoons were not mere commentary but part of the ethos of an emerging India — witty, critical, and democratic. His drawings taught readers to look at leaders without reverence, to see politics through humour as much as history.

Shankar has that rare gift, and without the least bit of malice, he points out the weaknesses and foibles of those on the public stage.

By the time Shankar’s Weekly appeared in 1948, he was already a respected figure. His cartoons had targeted the British Raj as much as Indian leaders, always with sharp but civil humour. Jawaharlal Nehru admired him deeply, even as he was often Shankar’s subject.

“Don’t spare me, Shankar,” he famously told him.

Nehru later explained why satire mattered: “Shankar has that rare gift, and without the least bit of malice, he points out the weaknesses and foibles of those on the public stage. It is good to have the veil of our conceit torn occasionally.”

This unusual climate — Gandhi’s ethical compass, Nehru’s democratic tolerance, and Shankar’s artistry — gave satire the space to flourish as reflection rather than ridicule. With this confidence, Shankar launched his weekly.

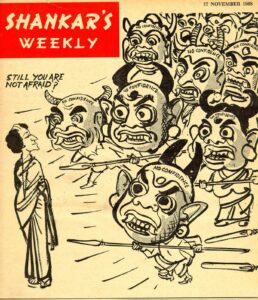

Modelled on the Punch, a British weekly magazine of humour and satire, it quickly acquired a distinct Indian voice. Nehru inaugurated the magazine, though he was often lampooned in its pages. For nearly three decades, Shankar’s Weekly was irreverent, fearless, and free of party lines. Shankar described it as “fundamentally anti-establishment, while never toeing any particular line.”

Shankar’s Weekly was India’s Punch.

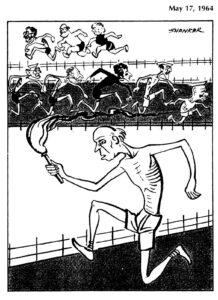

This independence gave it its bite. The magazine also nurtured young talents such as Kutty, Abu Abraham, and OV Vijayan, among others, who went on to shape Indian cartooning for decades.

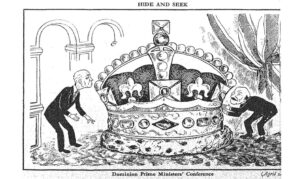

What also distinguished Shankar’s Weekly was Shankar’s extraordinary alertness to the world beyond India. His cartoons did not remain confined to domestic politics; they reflected global events with striking immediacy. Whether it was the Cold War, Mao’s victory in China, the Vietnam War, Afro-Asian solidarity or even the developments on Wall Street, Shankar could capture complex international developments overnight and render them into witty, incisive images.

The Weekly’s appeal lay not only in its wit but in its craft.

This global outlook gave the Weekly a breadth unusual for the time and helped readers see India’s place in a rapidly changing world.

The Weekly’s appeal lay not only in its wit but in its craft. EP Unny, Chief Political Cartoonist at The Indian Express, recalled its understated elegance: “Though printed in monochrome, and occasionally in two colours, Shankar’s Weekly was elegantly produced. The cover was always a cartoon, the layout simple and uncluttered. Even the smallest drawings were reproduced with great care.”

Shankar insisted humour deserved the same respect as literature or fine art. Every line and caption was deliberate; readers lingered, absorbing how humour could be serious without being heavy.

The writing matched the visuals. As Unny noted, “You could read exceptionally good English in it. The articles never chased shallow jokes. Humour came naturally, rooted in the writer’s context.”

In this blend of art and prose, the Weekly became a cultural bridge, introducing Indian readers to global counterculture. Through it, Jules Feiffer’s cartoons reached India, carrying echoes of Woodstock and the Beatles, and showing that the personal was also political.

Every line and caption was deliberate; readers lingered, absorbing how humour could be serious without being heavy.

This openness linked the Weekly with India’s own “little magazine” movement, especially in Kerala, where radical journals experimented with new forms of literature. Feiffer’s work in Shankar’s Weekly felt like their visual cousin, placing satire alongside dissenting literature in India’s cultural landscape.

Many journalists later admitted that it was their first encounter with political writing that was playful yet profound.

What made the Weekly stand apart was also its reach. Though based in Delhi, its readership extended deep into small towns and colleges, where young readers eagerly awaited each issue. In places where newspapers carried stiff political prose, Shankar’s Weekly offered a different idiom—one that was light in tone but heavy in implication.

Many journalists later admitted that it was their first encounter with political writing that was playful yet profound. In this sense, the magazine seeded an appetite for satire across India, ensuring that humour became part of the nation’s democratic vocabulary.

By 1975, however, the journal was exhausted. Two months into the Emergency, Shankar folded it up. While many felt censorship killed it, he wrote otherwise: “We could have taken the Emergency in our stride, but the burden of running a weekly on a shoestring budget was too much.”

Jawaharlal Nehru admired him deeply, even as he was often Shankar’s subject.

Yet, the timing was symbolic. At the moment when free speech was under greatest strain, the silencing of India’s most fearless satirical voice felt like more than coincidence. Even Indira Gandhi wrote to Shankar acknowledging the loss: “It takes a great deal of strength of mind to close down what one has built through years of care and labour… We shall miss the journal.”

The last editorial of 31 August 1975 remains one of the most poignant farewells in Indian journalism. Shankar reflected on 27 years of political change, then turned inward: “In our first editorial we made the point that our function was to make our readers laugh—at the world, at pompous leaders, at humbug, at foibles, at ourselves. But what are the people who have a developed sense of humour? It is a people with a certain civilised norm of behaviour, where there is tolerance and a dash of compassion.”

He warned that dictatorships cannot afford laughter, and lamented that the world, and India, had grown grimmer.

Yet he closed on hope: “Despite the present situation, the world will become a happier and more relaxed place. The spirit of man will in the end overcome all death-dealing forces and life will blossom to a degree where humanity will find its highest purpose discharged. Some call this God. We prefer to call it human destiny.”

What does the fiftieth anniversary of its closure mean for us today? Perhaps, satire is not indulgence but democracy’s safety valve. Gandhi’s counsel defended its ethics, Nehru’s tolerance affirmed its democratic role, and Shankar’s own warning reminds us of its fragility.

The Weekly’s final editorial from LK Advani’s ‘A Prisoner’s Scrap-Book’.

The closure of Shankar’s Weekly was not merely the end of a magazine but the loss of a space where laughter and politics coexisted. Its legacy is clear: humour was never ornamental to democracy but integral to it. Its monochrome pages carried colour enough to expose power’s follies, while its restraint showed that laughter need not be cruel to be effective.

Fifty years on, as public life in India and beyond grows increasingly humourless, the pages of Shankar’s Weekly call us to memory. They remind us that satire can be sharp without malice, ethical as well as fearless, and that laughter, when free, remains democracy’s most civilised instrument.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).