PuTiNa said a successful poem assuages emotional excitement and uses contemplation to take the mind to a tranquil state.

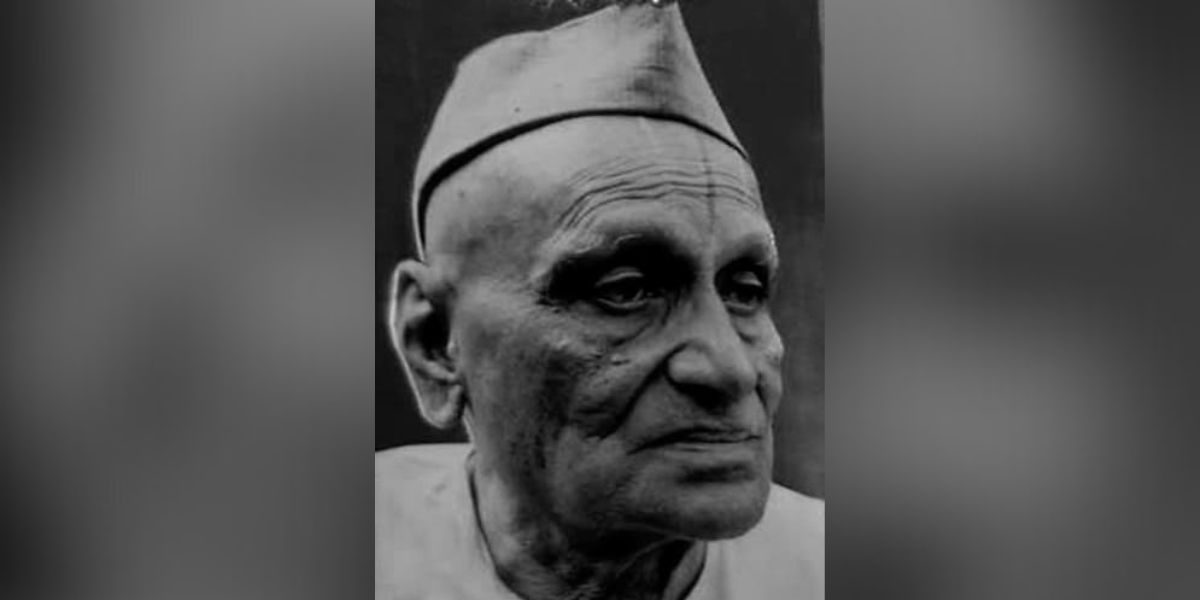

Shri Purohit Tirunarayana Ayyangar Narasimhachar (PuTiNa)

Shri Purohit Tirunarayana Ayyangar Narasimhachar (better known to the Kannada people as ಪುತಿನ or PuTiNa) was born in Melkote, one of the main pilgrimage centres of the Shri Vaishnava tradition.

Several centuries ago, his ancestors came to Melkote from Tiruvallur in Tamil Nadu. PuTiNa was born on 17 March 1905, the first son of Gorur Rangamma and Shri Tirunarayana Ayyangar. His father was a scholar in several fields, including the Vedas, Upanishads, Agama, Tarka, and Puranas.

The difference between the physical and socio-cultural environments of PuTiNa’s childhood significantly influenced him. If the natural surroundings unavailable to city dwellers were one reality, the other was his nourishment within a rustic intellectual environment without being rural. Strict restrictions of his upbringing honed PuTiNa’s natural intelligence and created a dreamer-poet with an introverted, shy character. Over time, PuTiNa grew into a person who was brave yet gentle, perspicacious yet reticent. Shri Goruru Ramaswamy Ayyangar has written about this aspect in his extended essay on PuTiNa.

The structured education of the traditional Sanskrit school he attended apart, PuTiNa, also received what might be called Western education. These two different types of education moulded his character in complementary ways.

Recollecting his school days, PuTiNa says, “My singularities were encouraged by knowledgeable teachers and friends. It was my good fortune to have such wise and helpful well-wishers. These mentors were wise enough and astute enough to recognize that behind my lack of interest in acquiring academic knowledge and my propensity for solitude lay a character that felt intensely.”

Given this background, it is natural to wonder how PuTiNa acquired a familiarity with Kannada literature, especially its poetry. “We had good books in middle school. We were exposed to the works of Nagachandra, Kanakadasa, Purandaradasa, Sarvajna, Sugunaratnakara, Chudaratna; the Tripadi and Sangatya metres, Govina Kathe, and S.G. Narasimhachar’s translations of English poems. This was how I became familiar with basics like Kanda, Vritta, Shatpadi, Tripadi, Sangatya, etc.

“What is surprising is that the Kannada I learnt in middle school from teachers like Shri Mantri Sampath Kumara Acharya, Hemmige Deshikachar, and Parami Padmanabha was the foundation and the extent of my Kannada education. Later in high school or college, I had no contact with any Kannada textbook.”

The reason for the formal Kannada PuTiNa used in his works appears to lie here. It is remarkable how much Kannada he learned in twelve years of schooling between learning Tamil at home and Sanskrit at school.

PuTiNa’s professional career, which he began soon after receiving his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1926, is one of the curiosities of his life. Starting as a typist and a confidential secretary in the office of the Chief of Staff of the Mysore Army, he eventually became the editor in the Record Room and worked there for thirty-four years. Only after he retired could he find work more suited to his inclination. PuTiNa spent eight years as the editor of the English-Kannada dictionary at the Kannada Encyclopedia office and Mysore University.

In 1925, PuTiNa married Sheshamma, the daughter of Shri Rangacharya and Mrs Eggamma. They were married for some sixty years and had seven daughters and one son. As a father, PuTina exemplified how intellect and talent could propel one from the lower middle class to the upper middle class.

Throughout his life, PuTiNa’s literary output brought him both popularity and several accolades, including the Central Sahitya Akademi Award for his “Hamsa Damayanti Mattu Itara Rupakagalu” (1966) and an honorary doctorate from Mysore University in 1971. He was also selected as the president of the 53rd Kannada Sahitya Sammelana held in Chikkamagaluru in 1981. The well-known poet S.R. Ekkundi authored a booklet on PuTiNa and a collection of poems about PuTiNa, titled ‘Yadugiriya Veene‘ (The Veena of Yadugiri) was published in 1981 as a tribute to him.

P T Narasimhachar’s literary oeuvre encompasses various genres, including poetry, drama, essays, lyrical prose, philosophical essays, poetic reflections, and translations. However, what permeates all of his writing, regardless of genre, is a poet’s sensibility and perspective. Ideas found in Indian poetics profoundly influenced PuTina’s understanding of poetry and its goals. According to PuTiNa, poetry aims to assuage rather than provoke emotional excitement. According to PuTiNa, a poem that stirs us as daily experiences do is unsuccessful. Instead, a successful poem uses contemplation to take the mind to a tranquil state.

Another matter repeatedly mentioned in connection with PuTiNar’s poetry is spiritual consciousness. Many of his song dramas and other poetic works indeed consist of characters possessed of charmingly naive devotion and belief. However, PuTiNa was never as interested in devotion as in knowledge. As he himself says, “ನನ್ನ ಮನಕೊ ನೀನೊಂದನುಮಾನ / ನನ್ನೆದೆಗೂ ನಿನ್ನರಿತ ಸುಮಾನ” (nanna manako neenondanumaana / nannedego ninnarita sumaana), meaning “To my mind, you are an uncertainty/though my heart’s delighted at knowing you.”

The reason PuTiNa remained like an island within Kannada poetry would seem to be the “stalled” nature of his poetic creation. From his first collection, “Hanate”, to his later collections, he was indifferent to the transitions in Kannada poetry.

PuTiNa published almost as many plays (mostly musical dramas) as he did poetry collections. It is interesting to note how, in 20th-century Kannada literature, there is a tradition of literary plays – that have not been staged – that has evolved parallel to plays written for and enacted on stage. Within this tradition, PuTiNa’s plays stand out; his sensibility, steeped in Carnatic classical music, was responsible for plays that posed a significant “staging” challenge to even modern theatre. As a consequence, such plays as “Ahalye“, “Gokula Nirgamana“, “Shabari“, “Kavi“, and “Shrirama Pattabhisheka“, though broadcasted as radio plays, very rarely went from the page to the stage.

PuTiNa drew inspiration from various sources, including folk forms such as Yakshagana and Bayalaata, classical music forms, Western musicals, and entirely musical Tamil plays. The result was plays that managed to integrate music and literature harmoniously. In incredibly melodic plays, meaning takes a backseat to melody, like in the compositions of our vaggeyakaras (writer-composers). However, Putina ensures that the music carries the mood and enhances the overall impact of the play.

The play “Ahalye” is one of PuTiNa’s finest literary creations. Set in a mythological narrative, its genius lies in identifying and re-creating turmoil and conflict in the hearts of men and women across space and time.

Ahalye’s life, with its ups and downs, explores contrasting facets of attraction and repulsion within male-female relationships. The play holds marital love as the ideal and extra-marital love as destructive. However, its real significance lies in its compassionate portrayal of more tragic characters.

A final word about PuTiNa’s achievements and contemporary significance. Despite the growing number of college graduates, people interested in “other” literature – like PuTiNa’s – are increasingly shrinking. An analysis of the literary and cultural events that have led to this is intriguing. Highly potent external forces influence our ‘present’ life and result in the severing of our ties with the past. People whose thinking is entirely informed by the present may find a poet like PuTiNa irrelevant.

But this is merely how it appears. It becomes apparent to those reading PuTiNa’s poetry and prose that his mind had absorbed scientific progress within his lifetime. But PuTiNa’s temperament preferred measuring the modern on the touchstone of ancient wisdom. To those who understand ‘Orientalism’ by Western intellectuals in the last forty years, the magnitude of PuTiNa’s achievements is evident.

Additionally, PuTiNa’s writing takes on a special philosophical significance. It refuses to separate ‘those times’ and ‘these times’. Instead, it seeks to understand all human beings’ inner tumult and seeks ways to alleviate it. Perhaps more importantly, PuTiNa’s work emerges victorious even if one defines literature as the art of using language. For all these reasons, I reckon PuTiNa, without a second thought, is one of the architects of modern Kannada literature.

(The writer is a senior Kannada literary critic and translator and a retired professor of Kannada literature. He has received several awards, including the Rajyotsava Award and the Karnataka Sahitya Academy Award.)

( Madhav Ajjampur, writer and translator, translated the article from the original Kannada. His essays, poems, and translations have appeared or are forthcoming in publications such as ‘The Hindu’, ‘EKL Review’, ‘Midway Journal’, ‘Kyoto Journal’, and ‘Modern Poetry in Translation’. His first book is ‘The Pollen Waits On Tiptoe’ (2022).