As Perumal Murugan navigated through his early years, a mix of frustration, anger, and denial shaped his developing psyche.

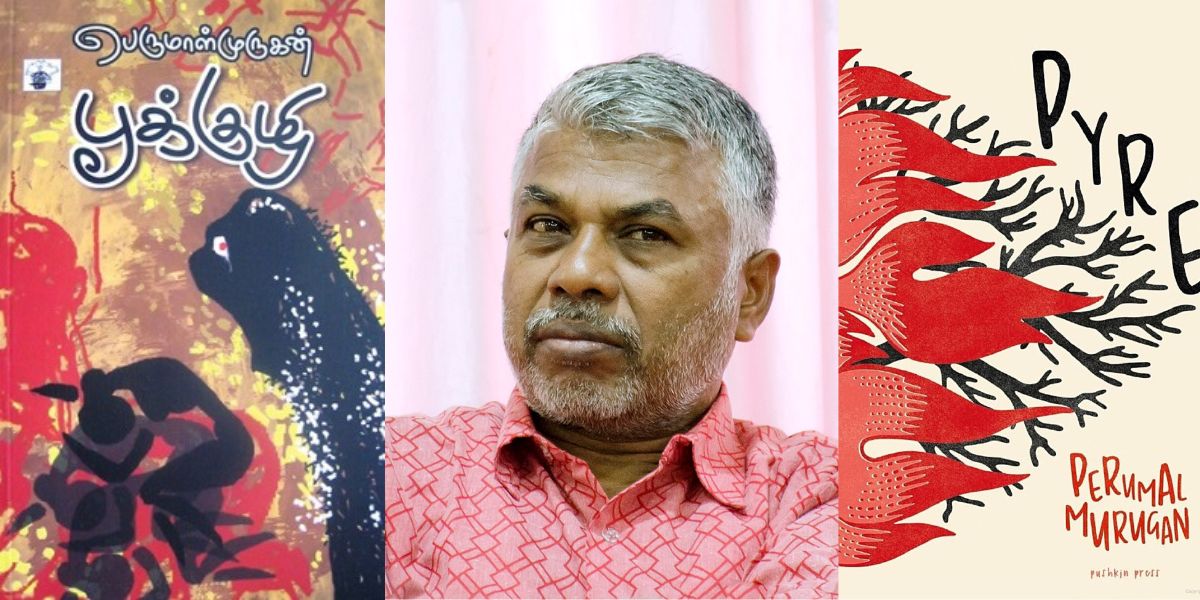

Perumal Murugan, and the covers of both Tamil and English version of Pyre. (Creative Commons)

From the quaint village of Kootapalli to the complexities of rural Tamil Nadu, author-journalist Saket Suman explores the power of resilience, societal taboos and the transformative essence of storytelling that shaped Perumal Murugan’s character in his formative years. This is the second of the ten-part series exclusively on thesouthfirst.com.

He was born in Kootapalli village, near Tiruchengode in Tamil Nadu, with the blessings of Lord Murugan, the Hindu god of war and the son of Shiva and Parvati. His parents, Perumayi and Perumal, led a simple life untouched by modern influences.

However, the rural Tamil setting of the 1950s was steeped in superstitions, prejudices, and taboos, which often governed societal behaviour. Despite the challenges, they didn’t view their lives as tragic, which wasn’t always pleasant.

Perumayi suffered a miscarriage during her initial pregnancy, causing her significant pain over two consecutive days. As her condition worsened, she was promptly taken to Tiruchengode General Hospital, where doctors were able to save her life but not that of the child. In their immediate community, being unable to bear children carried a social stigma.

Hurtful comments like “She can’t even have her own child; what’s the point of being a woman?” or “No offspring means no heir, hence the end of their family line” were unfortunately common for childless couples to endure.

A few years later, they welcomed their first child, hoping that the criticism they faced would diminish. However, the criticism took a darker tone when they didn’t have another child for four years. Rumours spread in the village, suggesting they might be unable to conceive, especially given Perumayi’s previous miscarriage.

This constant scrutiny led their neighbours to view them with suspicion, and they endured regular taunts, which brought them great shame. The couple’s mental well-being suffered greatly from the relentless teasing, and given the circumstances, their trauma was understandable. They were desperate to find a solution to free them from this daily ridicule.

About 150 kilometres from their village lie the Palani hills. Legend has it that when sage Narada presented Shiva with the “gnana-palam,” or the fruit of knowledge, he decided to award it to one of his sons who would first go around the world thrice.

The fruit couldn’t be divided and had to be given whole to just one person. While Karthikeya embarked on a journey around the world on his peacock mount, Ganesha argued that his world consisted of his parents, Shiva and Parvati, and thus circumambulated them. Ganesha emerged victorious in the challenge and was granted the fruit, leaving Karthikeya, also known as Murugan in South India, dissatisfied.

Consequently, he became a hermit in the Palani hills, where the Palani Murugan temple was eventually constructed. It’s believed that prayers offered at this temple are always answered.

The temple became the couple’s final refuge. Perumal would visit the temple every Krithigai day over the years and pray for the lord’s blessings to end their suffering.

His prayers seemed to be answered when Perumayi became pregnant once more. A few months later, they resolved that if their baby were a boy, they would name him after the god who had answered their prayers.

After waiting for their Murugan for four years, the entire family breathed a sigh of relief on October 15, 1956, when the young lad finally entered the world.

Perumal, attributing his newfound fatherhood to the blessings of Lord Murugan, decided to name his newborn after the deity, following the Tamil tradition of incorporating the father’s name as a prefix.

This marked the beginning of Perumal Murugan’s journey. Despite the challenging circumstances of his upbringing, he would later emerge as a celebrated figure in Tamil literature.

Young Murugan was born into an agricultural family that owned 11 acres of land, shared among Perumal, his two brothers, and their parents. Perumal’s parents cultivated two acres for their sustenance, while the remaining nine were divided equally among the brothers, each owning three acres.

Although they all lived nearby, it wasn’t a joint family setup; each brother had a separate dwelling. In Perumal’s portion of the land, half benefitted from canal irrigation while the rest relied on rainwater. Agriculture relied heavily on weather conditions, with abundant rain resulting in higher yields and poor monsoons, reducing harvests.

Deep wells were their primary water source, requiring constant deepening over time. During water shortages, they cultivated millet, chillies, and cotton, choosing crops that could also serve as fodder for their cattle.

Their agricultural output barely met their needs, leaving little surplus for trade or sale. To supplement their income, Perumal and his brothers took on part-time jobs.

His elder brother worked as a driver, initially transporting villagers to markets and fairs before transitioning to driving a lorry. The younger brother, on the other hand, transported rice sacks using his bullock cart.

From a young age, Murugan noticed the financial struggles his family faced. Yet, he didn’t perceive it as a deficiency, as many around him were in similar situations. Life seemed inherently challenging, and embracing this struggle was a form of divine acceptance.

Perumal started selling soda at the market, eventually becoming a successful business. Agriculture wasn’t merely a job but a cherished way of life for them. Despite Perumal’s absence due to managing the soda business, Perumayi diligently tended to the fields, even while battling Parkinson’s disease.

Following Murugan’s birth, relatives gathered at their home to celebrate. Murugan’s upbringing involved a natural process of learning and acceptance. Living amongst close-knit families and relatives facilitated constant interaction and knowledge exchange, especially concerning rural life and mythological tales. This environment instilled in Murugan a profound understanding of his roots and upbringing.

Learning was integral to Murugan’s life, although he didn’t actively pursue it. His grandfather shared numerous anecdotes, while his grandmother narrated fables and moral stories alongside her life experiences.

It seemed as though she was recounting her entire life to young Murugan.

During the hot summer, the children would gather and sleep on rope cots outside their grandparents’ home. The vast open space became Murugan’s first canvas as he gazed at the stars, attempting to understand their formations.

Despite their splendour, he was often distracted. The elders would join them, discussing their lives late into the night. With the gentle music of the breeze and the hum of bees in the background, Murugan began to grasp things beyond his years.

His early knowledge stemmed from these moments, though not necessarily formal education.

Our upbringing and surroundings largely influence who we become in life. Murugan realised early on that accumulating wealth wasn’t a priority for the people around him; survival was their main concern.

Living in an agrarian society surrounded by relatives, Murugan gradually learned the fundamental aspects of rural life.

Murugan’s parents were profoundly grateful to the divine despite lacking many privileges. Rising early each morning, they would consume porridge before venturing to toil in the fields without complaint. Regardless of nature’s adversities, they endured, diligently tending to the land, nurturing crops, and caring for their livestock.

Even in the dead of night, when the cattle stirred, they would tend to their needs without hesitation, tying their goats to their cots to ensure they wouldn’t miss a single movement.

To Murugan’s family, their livestock were not mere animals but cherished members of the household, fostering a symbiotic relationship within their ecosystem where communication and mutual understanding flowed effortlessly among trees, animals, and humans, each playing their role in maintaining harmony.

Reflecting on his upbringing, Murugan recalls his family never faced food shortages or the need to amass wealth; they were content with their modest existence. Their minimalistic approach to life found joy in hard work and simple pleasures.

Forming bonds with the cattle, Murugan spent hours playing and communicating with them, finding solace in their companionship. The animals understood his gestures and responded in kind, fostering a sense of mutual understanding and connection.

Over time, Murugan began to understand his surroundings better. He could distinguish flowers from bees and became attuned to the changing seasons, recognising the transition from dawn to dusk and the arrival of rain, storms, thunder, and breeze.

These natural occurrences became more discernible to him. As he navigated through his early years, a mix of frustration, anger, and denial shaped his developing psyche.

Reflecting on his upbringing in the 1950s, a pivotal era for India post-independence, Murugan remembers a starkly different landscape. The nation was grappling with the aftermath of British rule, facing economic challenges and a lack of basic amenities.

His village lacked electricity, plunging it into darkness after sunset—a recurring fear for him. Each night brought dread as he clung to his mother, Perumayi, seeking solace in her presence. Despite her efforts to alleviate his anxiety, moments of panic would seize him when left alone in the dark, prompting visits to a village priest for intervention.

The priest offered prayers, applied sacred ash (vibhooti) to his forehead, and adorned him with a protective talisman to ease his distress. Murugan cherished the sacred ash, keeping it under his pillow as a source of comfort and protection.

While he acknowledges the fear of darkness from his early years, his recollections are somewhat hazy due to his tender age. However, his mother later shared with him the anxiety they felt over his unexplained fear, shedding light on a challenging aspect of his childhood.

One couldn’t fault Perumayi for her actions. Like every mother, she deeply cared for the well-being of her child, especially considering the societal challenges she had endured before Murugan’s birth.

He meant the world to her, and she was determined to shield him from life’s hardships. Her protective instincts were evident as she watched him, ensuring he was safe even during mundane tasks like cooking or tending to the cattle.

Perumal Murugan’s fear of the dark elicited intense reactions, but Perumayi’s immediate comfort and reassurance always soothed him. Over time, he adjusted to the night, although residual fear lingered. Perumayi’s nurturing had a considerable impact, handling his fears with empathy and shielding him from ridicule.

Despite overcoming his fear, Murugan developed a strong attachment to his mother, experiencing anxiety at even brief separations. His early struggles with anger stemmed from frustration, a fact not widely known.

His brother was four years older than him, and all his friends were also older, making it difficult for Murugan to play with them. Conversely, his uncles’ daughters were around his age, so he naturally spent most of his time with them.

The boys in the village, including his cousins, teased him for what they perceived as feminine traits. Although he didn’t fully grasp the meaning, he sensed their mockery and felt irritated whenever they teased him.

This behaviour encouraged other family members to join in, hoping to provoke his reaction. Initially, he withdrew into himself, but gradually, he began to venture out again.

As a child, unable to discern gender differences clearly, Murugan found companionship among girls his age. He participated in their games and songs, feeling more comfortable with them than with older boys. However, the teasing persisted. “He is a she,” they would say.

It became intolerable when one of his uncles relentlessly taunted him, belittling Murugan and his parents. One day, unable to bear it any longer, Murugan lashed out, throwing a stone at his uncle, causing a severe injury.

Despite his aunt’s protests, Murugan had reached his breaking point. “She teases me too,” he thought before unleashing his anger on her, ensuring she would think twice before teasing him again.

Perumayi cradled her son in her arms, sternly reprimanding him and cautioning him of grave consequences should he repeat his violent actions. Murugan, however, found a strange satisfaction in his deed, an emotion foreign to him until then.

Believing he had sought retribution for past taunts, his anger swelled further. Recollections surfaced of childhood injustices, particularly his elder brother’s pilfering of his weekly snack rations.

Despite his best efforts to preserve his share, his brother’s thievery never failed to incite fury within him. One fateful day, he caught his brother red-handed, unleashing his pent-up rage upon him. Perumal Murugan attributed his rebellious demeanour during childhood to ridicule endured for his choice of companionship, compounded by an irrational fear of darkness that tethered him to Perumayi’s side.

Constant comparison to his brother, exemplified by their differing experiences in learning to swim, exacerbated his sense of alienation. Despite familial pressure, he resisted, finding solace and bonding with Perumayi through her patient tutelage in swimming.

His father’s persistent comparisons only deepened his feelings of isolation, fostering a defiant disposition against any form of exclusion or discrimination from an early age.

(Saket Suman is an independent journalist and the author of The Psychology of a Patriot. In the coming weeks, he will reveal the depths of Perumal Murugan’s struggle for literary freedom as creativity battled against persecution. The first part can be accessed here. Next Week: How Perumal Murugan’s Odyssey of Self-Expression Transformed Him from Introvert to Wordsmith)

(Edited by VVP Sharma)

Jun 14, 2024

Jun 07, 2024

May 31, 2024

May 24, 2024

May 18, 2024

May 10, 2024