Published Feb 15, 2026 | 6:53 PM ⚊ Updated Feb 15, 2026 | 6:53 PM

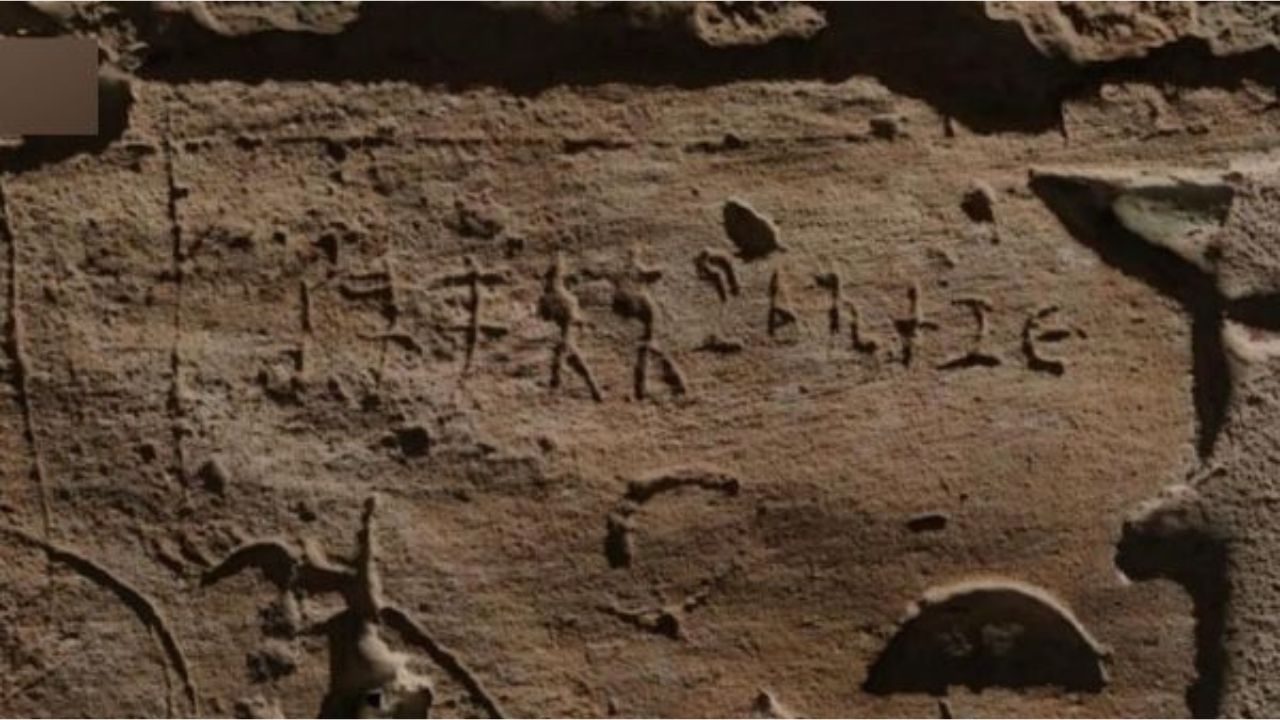

Tamil name Cikai Korran appeared eight times on five tombs.

Synopsis: According to several archaeological texts, ancient Tamils were master voyagers. During this golden era of navigation, a sophisticated network of strategically positioned ports remained under firm Tamil sovereignty, serving as the primary gateways for international exchange.

The ancient Tamils were master voyagers who traversed the world’s oceans, driven by a relentless pursuit of commerce and prosperity.

The legacy of these maritime endeavours is not merely a matter of oral tradition; it is firmly etched into the annals of history, from the evocative verses of Sangam literature to enduring stone inscriptions, copper plates, and the detailed chronicles of contemporary foreign scholars.

The reach of the Tamil trade was staggering in its geographic breadth. Beyond the internal routes to Pataliputra on the Ganges, their sails were a common sight in:

During this golden era of navigation, a sophisticated network of strategically positioned ports remained under firm Tamil sovereignty, serving as the primary gateways for international exchange.

The depth of engagement with the Western world is vividly captured in the Greco-Roman travelogue, The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. This seminal text specifically highlights the exquisite pearls of Korkai, ranking them as unparalleled in value and quality.

Furthermore, the geographical and historical treatises of Pliny and Ptolemy offer external validation of the grandeur of Tamil ports and their robust maritime connectivity.

These literary accounts are mirrored by tangible evidence on the ground: Excavations at Keeladi have brought to light Roman coinage and distinctive Arretine and Rouletted pottery, providing a material bridge between the Tamil heartland and the Mediterranean.

The poet Marokkathu Nappasalaiyar states in Purananuru (126: 14-16):

“Sinamigu thaanai vaanavan kudakdalpolantharu

Naavaai ottiya avalipirakalam selkalathu anaiyem”

Which says, When the Chera King, with his fierce army, sails his great golden ship across the western sea, no other vessels can navigate those waters.

Similarly, Manimekalai (16: 13-16) mentions that sailors from various countries speaking different languages resided in Puhar.

“naliyiru munneer valikalan valava;

otimaram parri, urthirai utaiya”

Archaeological excavations in places like Alagankulam near Mandapam in Ramanathapuram district and Arikamedu in Puducherry have yielded Egyptian potsherds, pottery engraved with female figures, beads, and coins from the Nanda dynasty.

Every day, archaeological data and Sangam literary verses continue to provide clarity and leave us in awe. In that regard, another joyous discovery reached us last week.

Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions have been discovered at the entrances of tombs in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, offering striking evidence of deep trade links between ancient Tamil Nadu and the Roman world. The inscriptions were found in the Theban Necropolis, near present-day Luxor.

The findings were presented at the International Conference on Tamil Epigraphy in Chennai by Professor Ingo Strauch of the University of Lausanne and Professor Charlotte Schmid of the École française d’Extrême-Orient, under the title “From the Valley of the Kings to India: Indian Inscriptions in Egypt.”

The research builds on the work of French scholar Jules Baillet, who studied the Valley of the Kings in 1926 and documented more than 2,000 Greek graffiti.

Revisiting the site, the current team recorded Indian inscriptions in six tombs. Their study shows that the engravers came from the northwestern, western, and southern regions of the Indian subcontinent, with southerners forming the majority.

Professor Strauch said the discovery came as a surprise. “I could hardly believe it when we first identified these inscriptions. Despite countless visitors over the years, the Indian connection had gone unnoticed,” he remarked.

Until now, evidence of Tamil contact with Egypt was largely centred on the Red Sea port of Berenike. These new inscriptions show that Tamil traders and travellers ventured deep into the Nile Valley. Archaeologists from the Tamil Nadu Archaeology Department suggest these points point to a well-established trade route linking the Malabar Coast to the heart of the Roman Empire.

The inscriptions appear to follow a common ancient practice, with visitors carving their names into monument walls to mark their presence.

Although Baillet recorded thousands of inscriptions nearly a century ago, the Indian scripts went unrecognised at the time. As a result, Tamil-Brahmi and Prakrit records remained unnoticed for decades.

This discovery adds to the expanding map of Indian epigraphy outside the subcontinent, alongside sites such as the Hoq Caves in Socotra and Berenike. Once the burial ground of New Kingdom pharaohs, the Valley of the Kings now also stands as evidence of the vast distances ancient Tamils travelled, leaving their names etched into global history.

During the Roman era, the Valley of the Kings was a site of great fascination, drawing travellers who left behind “graffiti” — personal markers of their presence.

When the French scholar Jules Baillet first surveyed these tombs between 1888 and 1914, he meticulously documented over 2,000 such inscriptions.

However, the Indian scripts remained a mystery to him. Recognising their foreign nature but unable to decipher them, he simply labelled them as “Exotic” or “Asianic.”

The current breakthrough has finally decoded these “exotic” markings across six specific tombs (numbered 1, 2, 6, 8, 9, and 14), revealing a sophisticated linguistic landscape involving four distinct languages and three script systems:

Tomb No. 1 stands out as the most significant site for Indian epigraphy, housing 16 inscriptions — more than half of which are in Tamil. Furthermore, this tomb holds the longest Indian inscription found in the valley.

Written in Sanskrit, it records the visit of an envoy of the Kshaharata Kings, who ruled Western India starting in the 1st century AD.

This specific historical reference serves as a vital chronological anchor, dating the presence of these Indian travellers to the early centuries of the common era.

Among the various voices echoing from these walls, none is as persistent as Cikai Kotran. His name appears eight times across multiple tombs, suggesting he was a traveller of significant intent.

Etymological roots:

Beyond Cikai Kotran, other names emerge from the stone:

While Greek graffiti is abundant within these tombs, the Indian inscriptions — predominantly Tamil — occupy unique positions.

The reach of ancient Tamil trade is underscored by a staggering volume of archaeological evidence. A comparative analysis of 130 ancient symbols from nations such as China, Egypt, Sri Lanka, Japan, and Greece against the Tamil Megalithic symbols reveals a profound correlation.

Specifically, 121 symbols match those found in Egypt, 103 with China, 94 with Japan, and 64 with Greece.

Further evidence of Egypto-Tamil trade exists in the Red Sea ports of Quseir al-Qadim and Berenike, where pottery shards featuring Tamil-Brahmi (Thamizhi) inscriptions dating from the 1st century BCE to the 1st century CE have been unearthed.

Similarly, the widespread discovery of Greek coinage across Tamil Nadu serves as a tangible testament to the robust exchange with the Mediterranean.

Maritime archaeology further validates these links. A Persian-style ‘Stone Anchor’ dating back to 1000 BCE was discovered by researchers from the Tamil University of Thanjavur at Kurusadai Island.

This find points to ancient trade links reaching as far as modern-day Israel.

By 500 BCE, as Greeks acted as intermediaries in trade with Europe, the Tamil language began to leave a permanent mark on the Western world. This linguistic exchange is evident in botanical and trade terms adopted into Greek:

A nation’s strength is rooted in its commercial economy. The fact that the Tamils maintained such a dominant presence across the globe reveals their historical status as a formidable world power.

Sangam literary data, foreign chronicles, modern historical scholarship, and numismatic evidence all converge on a single truth: Tamils travelled, settled, and traded across the globe. To safeguard this vast maritime wealth, the Tamil kingdoms maintained sophisticated and powerful naval fleets.

Tamil land was a hub of continuous global commerce in history. This prosperity was not accidental; it was the result of a high degree of technological innovation, advanced agricultural production, and masterful trade management.

According to Periplus of the Erythraean Sea — English translation by WH Schoff — long before the 7th century BCE, the Tamils are said to have carried out trade through Arab intermediaries with regions such as Mesopotamia, East Africa, Egypt, Palestine, and even as far east as China.

Perhaps most crucially, it was sustained by the “United Alliance” of the three great Tamil monarchs as noted by the poet Mamulanar (Akananuru 31), whose collective protection ensured that the Tamil nation remained a sovereign and supreme force in international trade.

(Edited by Muhammed Fazil.)