Published Dec 14, 2025 | 8:00 AM ⚊ Updated Dec 14, 2025 | 8:00 AM

Differences between Dakhni and Urdu are stark. Dakhni shows evidence of influence from South Indian languages.

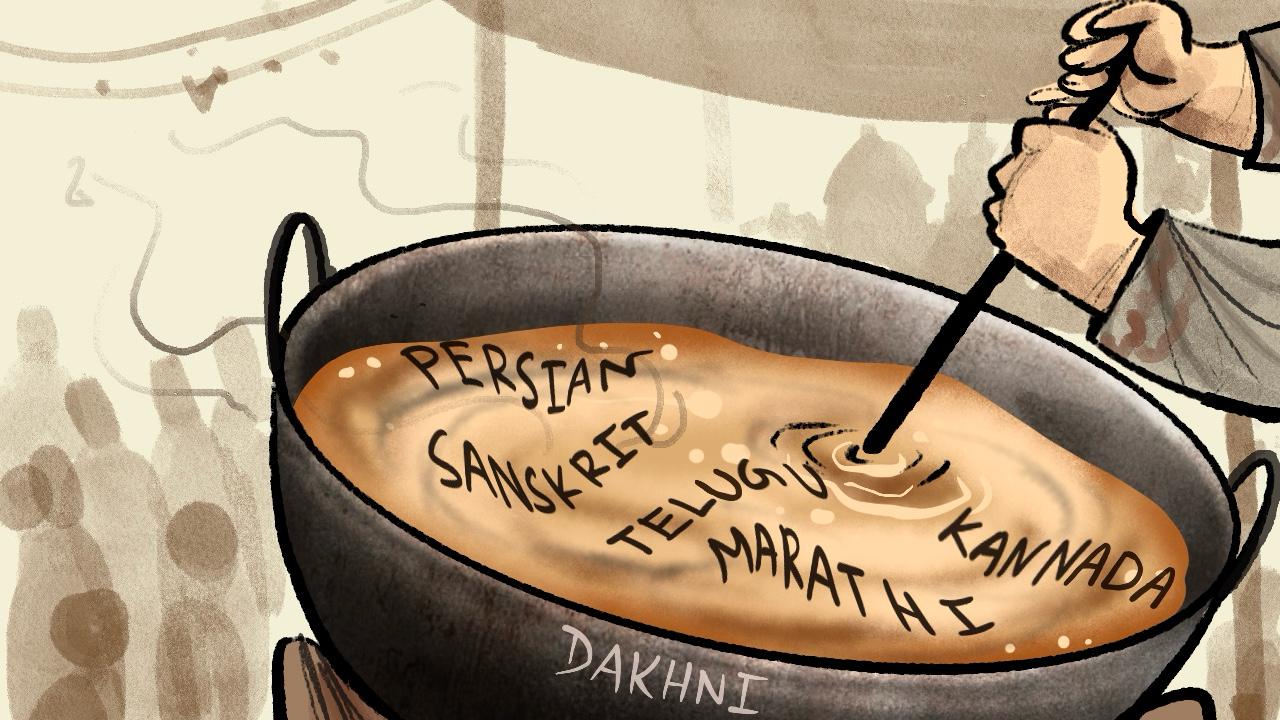

Synopsis: Dakhni began in the 14th century, when Dehlavi travelled south during the Tughlaq conquest. That spoken tongue, which was derived from Persian and Sanskrit, was mixed with the languages already rooted in the Deccan. Marathi was the biggest contributor, alongside Kannada and Telugu. There was also influence from the Persian and Arabic brought by the courts and Sufi traditions.

“Hau kaiku tension lete ji!”

“Aye miyaan.”

“Nakko yaar.”

Dakhni is a language that holds character. You see these lines, amongst many others, floating through reels and meme pages, sometimes used by the comic character in movies. It is instantly recognisable by a vast majority of people as ‘Hyderabadi Urdu,’ the city’s famous dialect.

Except it’s neither Hyderabadi nor Urdu.

The answer to the question of what it really is goes back centuries.

Yunus Lasania, a journalist and content creator from Hyderabad, noted in an article that Dakhni began in the 14th century, when Dehlavi travelled south during the Tughlaq conquest. That spoken tongue, which was derived from Persian and Sanskrit, was mixed with the languages already rooted in the Deccan. Marathi was the biggest contributor, alongside Kannada and Telugu. There was also influence from the Persian and Arabic brought by the courts and Sufi traditions.

What came out of the mix was not just slang, but a fully operative language.

“Sufis wanted to reach out to the general public,” says historian Sajjad Shahid. A scholar in Dakhni. He is also a visiting Professor at the University of Hyderabad.

“So, they tried all these experiments by using local vocabulary, borrowing from local iconography, local imagery, local similes, metaphors, and then in different places it evolved differently,” he says. “In the Deccan, it came to be known as Dakhni.”

But for the longest time, people didn’t want to admit that. They didn’t want to accept it as a language.

“Persian was supposed to be the language of learning, as with Sanskrit,” explains Shahid. “This language was a mixture. It was not considered to have the purity of any one lineage, neither Sanskritic, Persian, nor Arabic.”

A language that was made for the people was dismissed as soon as they found something more pure, something more sacred.

The same tongue that developed into Dakhni in the south travelled north and became the language of the commons.

What they didn’t realise then, or perhaps they chose to overlook it, was the fact that Dakhni had its own literature already.

“The earliest record we get is from the early 1400s,” Shahid said. “But even then, if you look at those manuscripts or those writings that survived from that period, you get an idea that it was already a highly developed language by that time.”

Those in power wanted their ideas to reach the people; they wanted to talk to them. And hence, they began writing in their tongue, Dakhni.

“So, this was Dakini. Now with Urdu, parallel things are happening there also,” explains Shahid. “But serious writing in this language did not occur there till a very late date.”

In this lies a paradox that Lasania has captured beautifully. “How can a language without any literature have a dialect? How can a dialect have literature before the actual language itself?”

He addressed the popular conception that Dakhni is just a dialect of Urdu, but it turns out that, logically, that cannot be the case. There is the question of the dating of the literature of the languages.

Parallelly, there is also the question of influence. Shahid added that Dakhni writing outdated Urdu. “And that too, after being imported into Delhi from the Deccan.”

He opined that it is not Urdu that influenced Dakhni, but the opposite way. The word ‘tuk’ is a defining feature of Lucknow poetry, but Shahid said he can provide a many examples of it being used in the Deccan first.

Dakhni has had a tradition of literary work behind it, but it lost its position as a written language by the 18th century.

Still, it never stopped being spoken of.

Today, we have reels, memes, film and music. The literature of the modern has a way of manifesting through these online, on-screen platforms.

Before putting anything in a public space, there are many things to consider, language being one of them. The language of the content will have an invariable effect on its reach, on the demographic of the audience.

“Because I think it all comes down to authenticity, right? And originality, said music composer and YouTuber Pasha Bhai, who made the first-ever Dakhni rap song, Eid ka Chaand.

“So if I’m a Bangalorean and I’m making music in Hindi or Urdu, it won’t have that same authenticity as someone from Lucknow or Delhi. Because the language would be more rooted for them,” he said,

Pasha said he felt like a tourist in that space. Dakhni, for him, creates a space that brings more authenticity to the table. A space where he feels at home, and where his audience feels at home. They feel a certain familiarity, he says, and that makes them relate to his music more.

But even Pasha is not ignorant of the fact that people often play a character for the screen, especially on social media.

“See, the people who are posting these things online are not really like that in real life,” he says. “I would have to accept that. They’re not really that expressive or energetic.”

This does not necessarily point to misrepresentation, though. Historically speaking, the whole purpose of the language was to be relatable to the common people, to be representative of them.

Even so, it is the sad reality that the vast majority of people still see it as a Hyderabadi slang. They don’t know its name, even though they use it daily.

“Even though I know it’s Dakhni now, if you ask me what I speak, it’s Hyderabadi,” says 30-year-old Vijay Sharma. Brought up in Hyderabad, he has his maternal family in Nanded. The influences are clear as day.

“I’m just very used to Hyderabadi,” he says. “I’m very comfortable with it, so I don’t care about the name much.”

Dakhni is a language rooted in its usage, in its people.

What contributes to Hyderabadi Dakhni being the most popular one, according to Pasha Bhai, is the city’s pop culture.

“In mainstream films, in mainstream music, we’ve seen it. We’ve heard it,” he says.

“Even Salman Khan remixed that Miyabhai song during lockdown. So I think it’s only fair. We can’t really blame the people who associate Dakini with Hyderabad because it has had a pop culture.”

That may be one reason that the language gets associated with the city, but there is also more to the story, from back when Hyderabad was still a princely state.

“So, Hyderabad state was spread over major parts of the old Deccan,” says Shahid. “You had Marathwada here.”

Hyderabad, Bidar, Gulbarga, Usmanabad, Aurangabad, Parbani, Latur, and Raichur are all cities that speak Dakhni. Cities that are now not even in the same state as the modern city of Hyderabad were once a part of the princely state.

People from all these places associated themselves with Hyderabad because that was the centre of power. Even natives of nearby places said they were from Hyderabad, because that was the name that was widely known.

“So, what is your language? They’ll say Dakini,” Shahid states. “Where are you from? They’ll say Hyderabad.”

Most speakers may not think much of labels.

Linguistically speaking, the differences between Dakhni and Urdu are evident. Dakhni actually shows evidence of influence not from the latter, but from South Indian languages.

“And there’s a very clear classification because Dakhni has words from Dravidian languages. The sentence formation is very different from Urdu,” notes Lasanai. His example demonstrates the statement well.

In Telugu, you say ‘oka aidu minishalu aagu.’ In Dakhni, the same becomes ‘ek panch minute ruko ji.’

They directly translate to ‘one five-minute wait,’ a phrasing that makes complete sense to its speakers. Why is the ‘one’ there? No one has to question it; no one is confused.

Such a structure doesn’t work in modern Urdu at all.

The closer you look at Dakhni, the harder it gets to neatly categorise it. Not a dialect, not just slang, not Hyderabadi, not Urdu. Today, it lives in the gap between the streets and the official papers, between what people speak and what they are told they should instead.

Maybe that gap is finally getting the attention and acknowledgement that it should. Maybe it is finally edging closer to language than dialect.

“Once there is a space for conversation, we will get somewhere,” says Pasha Bhai. “The more the merrier.”

For now, that space is the internet, and the few people who are calling for more dialogue around it. It is a space where Dakhni may sometimes seem exaggerated, stylised and misunderstood, but it is at the same time spoken, noticed and discussed.

“It’s nice to hear as long as you’re used to it,” says Sharma.

For a language that survived mostly by being spoken, it is time people get used to it again.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).