Published May 17, 2025 | 8:00 AM ⚊ Updated May 17, 2025 | 8:00 AM

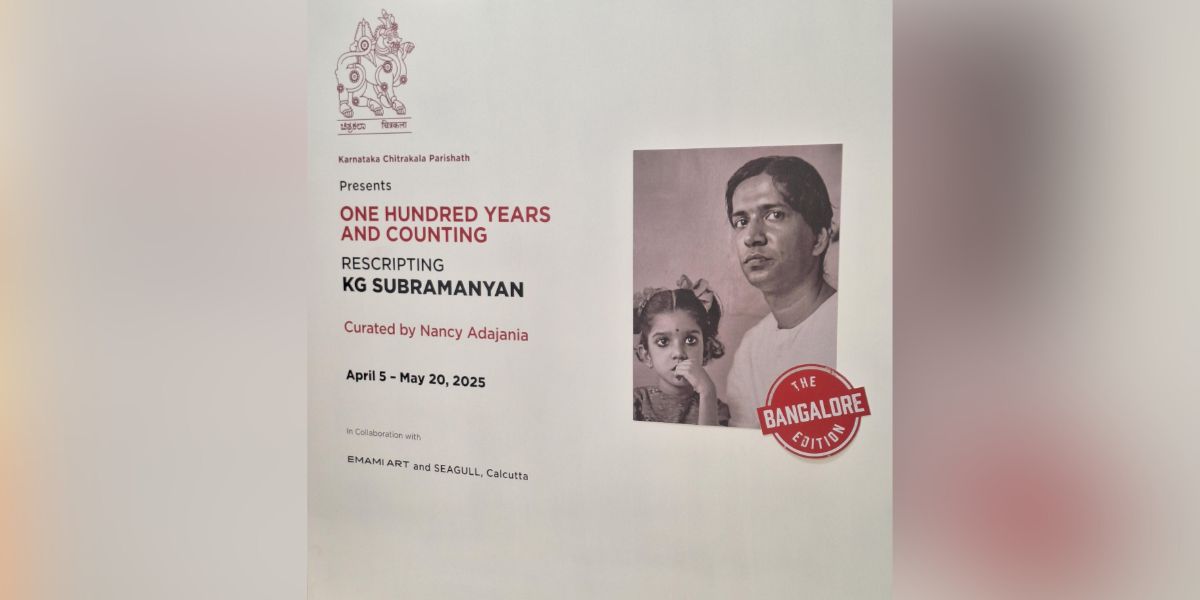

One Hundred Years and Counting: Rescripting KG Subramanyan.

Synopsis: Art curator Nancy Adajania is organising a multi-city exhibition celebrating the birth centenary of renowned artist KG Subramanyan. The exhibition’s pedagogy is not merely explanatory — it offers critical analysis and interpretative depth.

“In our increasingly commodified art world, curatorial practice is often perceived as a wannabe, glamorous profession. It is, in fact, hard work that is equal parts artisanal and imaginative labour,” art curator Nancy Adajania, who is organising a multi-city exhibition celebrating the birth centenary of renowned artist KG Subramanyan, told South First.

Titled “One Hundred Years and Counting: Rescripting KG Subramanyan”, the exhibition is hosted in Bengaluru by the Karnataka Chitrakala Parishath from 5 April to 20 May. It was held in Kolkata from 5 April 2024 to 21 June 2024.

This centenary show aims to reinterpret Subramanyan’s practice and make it relevant to the current political urgencies. To this end, the curator has created an immersive theatre of spectres and visions.

“In our bigotry-haunted times, I wanted us to remember KG Subramanyan’s steadfast belief in an inclusive, pluralistic world. Accordingly, I have devised my exhibition scenography such that large silhouettes, based on the characters from two of his children’s books (Robby and The Tale of the Talking Face), are strategically placed on the walls and floors of the gallery, as a warning against the forces of authoritarianism.

“Robby’s deceptively simple question — Do you think it is funny for one to be so many? — from the children’s book published in 1972 seems even more germane today, when being multiple is punished,” observed Adajania.

Born in 1924 into a Tamil Brahmin family in Kuthuparambu in north Kerala, Subramanyan was a renowned artist and a recipient of the Padma Vibhushan.

Deeply influenced by Indian folk art traditions such as the folk art of Kerala, Kalighat painting, and Pattachitra from Bengal and Odisha, as well as Indian court paintings, his work reflected a unique fusion of tradition and modernity.

The exhibition has 270 objects, including a variety of archival materials. It has Subramanyan’s early paintings from the 1950s, iconic reverse paintings on acrylic sheets, postcard-size drawings and toys made for the Fine Arts Fairs at the MS University, Baroda.

The exhibition also focused on his work process through a significant amount of archival material that has not been seen before, such as the handcrafted mock-ups of his children’s books, preparatory sketches for murals, the maquettes for the powerful mural The War of the Relics (2013) and Subramanyan’s 1970 letter to Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay on what the Crafts Council could do to improve the conditions of the craftspeople.

The Bengaluru edition of this exhibition also features rare works such as Girl with Cat Boy (1991), Chinnamasta (1991), Varanasi 2 (2007), and Devi 2 (2008), which have not been displayed anywhere in the past two decades. The viewers will also be entranced by the magnificent suite of paintings from the 1960s, from the Piramal Foundation, which bears testimony to a major transitional phase in the artist’s practice.

Unlike a conventional show, this is a research-based exhibition with critical annotations by Adajania to recontextualise KGS’s legacy.

“I wish to situate KGS’s artistic imagination in its larger contexts, at the cusp of familiar and unfamiliar histories, contending world views, unexpected connections and varied artistic lineages. To give a few examples from my research and exhibition mise-en-scene, I have placed Subramanyan’s toys next to Abanindranath Tagore’s all-but-forgotten miniature sculptures made out of discarded materials and found objects, kutum katam, shown rare archival footage of a shadowgraphy performance by Prasanna Raghava Rao from Karnataka (a fellow student of KGS from Santiniketan) next to the silhouettes of Subramanyan’s children’s books,” said Adajania.

The exhibition’s pedagogy is not merely explanatory — it offers critical analysis and interpretative depth.

“I use my wall texts as prompts or provocations to plant questions in viewers’ minds, or to confront viewers with an aesthetic, political or ethical dilemma. While my research and findings are art-historically rigorous, my tone is literary, even intimate, as if I am speaking nearby rather than instructing the viewer from on high,” said Adajania.

Visitors can find a lot of female figures, from Subramanyan’s paintings, at different stages of their lives. At the entrance, a miniature painting ‘Girl and a Mirror‘ (2003) glows like a composition in stained glass. The melancholic female figure resembles a ukiyo-e character. Adajania argued that Subramanyan’s representation of female figures could not be seen through the simple binaries of gender.

“While he often characterises his female figures as sexual playthings and, on some occasions, portrays them through a borderline misogynistic gaze. But you can’t easily put him in a box. Just when you think you are trying to define him, his work eludes categorisation and confounds you with its ambivalences and contradictions,” she pointed out.

Children’s books are often regarded as a minor genre in the maestro’s practice. However, Adajania chose to foreground them since it is possible to explore Subramanyan’s continuous thread of ‘political philosophising’ through these books as well as the maquettes of his murals.

“The mockups of KGS’s children’s book How Hanu Became Hanuman, published in 1995, which I’ve selected from the Seagull archive, are a treat for any viewer interested in how KGS composed his collages using humble materials — brown and black chart paper cutouts complemented by free-form graphic elements. These are acrobatic conceptions, with figures shaped by sharp paper cuts and calibrated into swift, rhythmic movements,” said Adajania.

She, however, added that people must question the patriarchal stereotypes. For instance, here the female protagonist is shown as a damsel in distress despite having a black belt in the martial arts.

Between 1958-61, Subramanyan was the deputy director (designs) of the Weavers Service Centre, All India Handloom Board, in Bombay. On the exhibition wall, there is an account of one of his success stories in textile design.

Artist Nilima Sheikh highlighted Subramanyan’s ingenious design solution for reviving the unsold stocks of ‘Bleeding Madras’ textiles in the 1960s.

As it happens, Sheikh also features in this show as one of four women artists, along with Pushpamala N, Mrinalini Mukherjee, and Sheela Gowda, who were deeply inspired by Subramanyan’s practice.

“An inexpensive plaid material, which came to be known as ‘Madras’, was originally made for the African market. Supply of this rose sharply following an expansion to the American market. However, fashions changed in the later years, and large unsold stocks piled up. Because the reds and blacks ‘bled’, Subramanyan tried discharge printing on the plaid. Right through the 1960s, printed ‘Bleeding Madras’ – a designer’s coup – remained both popular and economically viable,” Sheikh told South First.

Meanwhile, Adajania shared about one of her personal favourites, Girl with Cat Boy. In this painting, a masked child-woman with piercing eyes reveals her animal self, as her hands and feet gradually transform into claws.

“This painting is truly enigmatic. On the face of it, it may look like another variation on KG Subramanyan’s quintessential bahurupi or shapeshifting theme. But ‘Girl with Cat Boy’ resists interpretation. It reminds us that beneath the civilisational façade, it is the life of the instincts that determines the choices and actions of the self. It’s a work that definitely fascinates me,” said Adajania.

Some of Subramanyan’s most celebrated works include Untitled (Girl with Sunflower) (1952), Studio Still-Life (1962), The King of the Dark Chamber (1962–63), and Portrait Gallery (circa 1960s). He also created notable murals, such as the Black and White Mural at Kala Bhavan.

During India’s freedom struggle, Subramanyan was actively involved and was known for his adherence to Gandhian ideology. He also had a distinguished academic and professional career. He served as a Lecturer in Painting at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Baroda. He was a British Council Research Scholar in the UK from 1955 to 1956.

(Edited by Muhammed Fazil.)