Published Oct 19, 2025 | 8:00 AM ⚊ Updated Oct 19, 2025 | 8:00 AM

A Ramachandran's 'In Trance' at the museum. Chameli's works are in the background. (Supplied)

Synopsis: Ramachandran’s early works, born out of the trauma of partition and the dehumanisation he observed in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Delhi, were searing in their intensity. Headless, contorted bodies and satirical murals gave visual form to suffering and political decay, echoing the dramatic narrative of Mexican muralists. These early canvases were steeped in social conscience, bearing witness to human suffering and resilience, and a few are exhibited in the museum.

The Ramachandran Museum at Kollam, Kerala, is in many ways a posthumous homecoming for the Attingal-born artist.

Although A. Ramachandran spent the majority of his professional life in Delhi, the museum brings his vision, memory, and creative spirit back to Kerala, where his formative years shaped his sensibilities. Ramachandran’s life was a creative journey in search of beauty, but he always kept the memories of his childhood alive. Ultimately, it was an extension of that beauty, which he found in the tribal villages around Udaipur, that redefined his works.

“In the tribal villages and Baneshwar, I found an ideal world that satisfied all my aesthetic needs. Unlike the Gaudia Lohars, whom I could observe only from the distance without any direct encounter, the little Bhil villages gave the prodigal son who had left Kerala a second homecoming,” he wrote later. The characters in his monumental work Yayati were based on the life of Gaudia Lohars. But Udaipur changed his language further.

Each time he returned from Udaipur, he would regale the family with the smallest details and stories of his visits, remembers Sujata, Ramachandran’s daughter: “On one occasion, a young boy asked how much my father would charge for making his sketch. He asked the boy how much money he could pay, and the boy offered him the two rupees that he possessed,” she recalls.

Chameli and A Ramachandran.

Such moments reveal not only Ramachandran’s generosity and empathy but also his deep engagement with the lives and stories around him. It is this spirit—his curiosity, sensitivity, and human connection—that the museum, inaugurated on 5 October, seeks to preserve and celebrate.

Less than two years after his passing on 10 February 2024, Kerala now honours one of its most distinguished sons with a space that brings his life, his art, and his enduring vision back to the community that shaped him.

“The Ramachandran Museum at Kollam, like the K.C.S. Paniker Gallery at Thiruvananthapuram, is the happy outcome of the artist’s bequest and the state government’s gracious acceptance and decision to house it as a separate public collection. But what thoughts were behind the bequest and its acceptance, what was Ramachandran’s career like, and what artworks constitute this collection? “We shall look at them very briefly,” says R Sivakumar, art historian and curator of the museum.

The museum is carefully curated to mirror Ramachandran’s expansive vision.

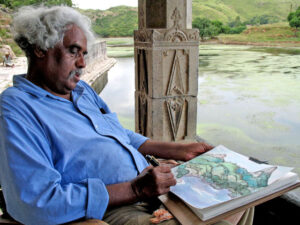

A Ramachandran (1935 – 2024) in Rajasthan.

Far from being a static display of objects, it encourages visitors to engage with the layers of his artistic journey, moving seamlessly between expressionist early works, satirical compositions, monumental lotus pond canvases, and intimate drawings, apart from the works in his personal collection that include Rajasthan murals and oil paintings from the post-Ravi Varma period. It is a space of encounter, where the viewer is invited to traverse the complex intersections of nature, culture, and humanity that Ramachandran explored in his life.

“Although Ramachandran spent his entire professional life in Delhi, his sensibilities were shaped by his early years in Kerala. The rural landscape of Attingal, which he explored, and the murals of its Krishnaswamy temple, which he regularly visited with his mother as a boy, planted the first seeds of his love for nature and the art of Kerala in his mind,” explains Sivakumar.

Born in 1935 in Attingal, Ramachandran’s childhood was steeped in Kerala’s visual and cultural traditions. The murals of the Krishnaswamy temple and the lush rural landscapes of his early years planted the seeds of his lifelong love for nature and the arts.

‘Dead Lotus Pond’, oil on canvas, 78×192, 2020.

Even when his family’s fortunes declined and they moved to Thiruvananthapuram, his interest only deepened—nurtured by music and literature. Writers such as Kunjan Nambiar and the progressive voices of the mid-20th century shaped his conviction that art must speak to society.

His move to Santiniketan for formal training brought him under the mentorship of Ramkinkar Baij and Benode Behari Mukherjee, who left a profound imprint on his artistic grammar. Santiniketan itself, with its unconventional environment and openness to difference, reinforced Ramachandran’s belief in art as a human, empathetic practice rather than a set of rigid rules.

Ramachandran’s early works, born out of the trauma of partition and the dehumanisation he observed in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Delhi, were searing in their intensity. Headless, contorted bodies and satirical murals gave visual form to suffering and political decay, echoing the dramatic narrative of Mexican muralists. These early canvases were steeped in social conscience, bearing witness to human suffering and resilience, and a few are exhibited in the museum.

‘Lotus Pond on Starry Night’, oil on canvas, 78×192, 2019.

Later, his focus shifted outward and inward at once. Drawn to Udaipur and the Bhil communities, he found in the vast lotus ponds of Rajasthan a living ecology, a motif that would dominate his mature work. No longer symbols alone, these ponds embodied life’s cycles of birth, bloom, decay, and renewal, reflecting a rhythm that mirrored human existence itself. His paintings and sculptures transformed these encounters into allegories of humanity’s bond with nature – expansive, rhythmic, and theatrical in their scale.

“Where modernists saw underdevelopment, he saw a lost way of life, and the large village lotus ponds, which progress-mongers saw as potential real estate, taught him the basics of ecology and the interdependence of planetary life. Even sympathetic viewers, who noticed his artistic mastery, thought he was a late romantic and missed his message. But that did not perturb Ramachandran; used to ploughing lonely furrows, he kept reiterating the possibilities beyond the modernist model of progress and the lingering possibilities of languages deemed redundant,” observes Sivakumar.

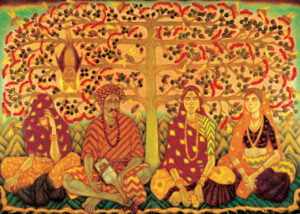

‘Song of the Simbul Tree’ (2001).

The museum captures this wide arc of Ramachandran’s career. The holdings include early expressionist works from the 1960s, trenchantly satirical paintings from the 1980s, and monumental lotus pond canvases, some stretching sixteen by six feet. The sculptures display the breadth of his experiments, from small symbolic objects and ceramics of the 1980s to the nine-figure installation, In Trance, and a monumental Gandhi sculpture, embodying truth, empathy, and moral conviction, with the word Ahimsa inscribed in all Indian languages.

Watercolours and drawings that were central to his practice, form another highlight, ranging from miniature-inspired Bhil life paintings to pen-and-ink drawings that stand on par with his canvases. His engagement with design is also represented: original artworks from his children’s books, created with pedagogic intent to nurture visual sensibility in young readers, as well as stamps designed between 1972 and 1982, including the iconic Dandi March commemorative stamp, are on display.

The museum, in association with Kerala Lalithakala Akademi, is also planning various publications to commemorate the artist. As the first step, five children’s books created by Ramachandran in collaboration with his wife Tan Chameli were released as part of the museum inauguration. The complete artwork of one of these books, Golden City, is also on display.

The Message of Mahatma

The museum preserves his personal collection of Indian art: five post-Ravi Varma Kerala portraits and 30 Nathdwara miniatures, reflecting his curiosity about Indian responses to academic realism and photography. Brushes, pigments, an apron, and his standing easel further lend an intimate sense of the artist’s daily practice.

The museum honours Chameli as well, and some of her paintings are also on display. Trained in Santiniketan and rooted in East Asian brush traditions, her delicate watercolours and ink works transform flowers, ferns, and waves into meditative spaces of stillness.

“I also had the opportunity to witness his mastery of drawing while assisting him in a project to copy the Kumārasambhava drawings of Mattancheri Palace for the Kala Bhavana Museum. But living with him and seeing his work process so closely was a revelation to me. I understood that he was not only a talented artist, but also a thinking artist and art was a sadhana for him,” Chameli recollects.

Nadhwara paintings from A Ramachandran’s collection.

Their shared vision underscores the museum’s spirit: a place where multiple creative sensibilities coexist, complement, and enrich each other. Ramachandran’s approach to art was never hierarchical. From large canvases to children’s books, stamps, and stage designs, he saw every medium as an opportunity to refine human sensibilities.

“Though we wished to open this museum during his lifetime, and Ramachandran himself had identified a few major works, it is his family who helped realise this vision after his passing. This is not just a tribute to him, but a step towards building a vibrant museum culture in Kerala,” said Murali Cheeroth, Chairman, Kerala Lalithakala Akademi, whose efforts played a crucial role in realizing this museum.

More than a collection of objects, the museum is conceived as a living cultural space, hosting interactive sessions, exhibitions, and programmes that cut across generations. Visitors encounter Ramachandran’s protest and empathy, theatre and meditation, humour and satire, nature and humanity—all within one evolving dialogue.

A Ramachandran in his studio.

Although Ramachandran never returned to settle in Kerala, his memories of its landscapes, temple murals, and people remained etched in his imagination, along with the humour of the place.

“When I left Kerala in 1957, I carried with me something peculiar to my place under my skin—a sense of humour. This is not an ordinary variety of humour. It is a combination of satire and humour—black humour,” he wrote later.

Today, that humour, that vision, and that love for Kerala return in the form of this museum—a homecoming that ensures his art continues to live, provoke, and inspire.

His studio was a sacred space, meticulously organized and dedicated to his craft, says son Rahul Ramachandran, who is a scientist with NASA. “Watching him work was a remarkable experience. He approached his art with a cerebral intensity, deeply absorbed in the process of thought, drawing, and painting,” he says.

The museum in Kollam.

From intimate watercolours to monumental canvases, from Bhil villages to Kerala temple murals, the museum presents Ramachandran’s oeuvre in all its complexity and richness. It also celebrates the role of family and collaboration, highlighting Chameli’s works, the children’s books they created together, and personal artefacts that make the artist’s practice tangible.

Each work is a dialogue with the viewer, asking them to slow down, observe, and reflect. By blending the personal and the ecological, the political and the meditative, the museum creates a space where art, memory, and cultural heritage converge. In doing so, it establishes a benchmark for museums in Kerala – not just as repositories, but as dynamic, living spaces of learning, reflection, and inspiration.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).