Published Jan 16, 2026 | 8:00 AM ⚊ Updated Jan 16, 2026 | 8:00 AM

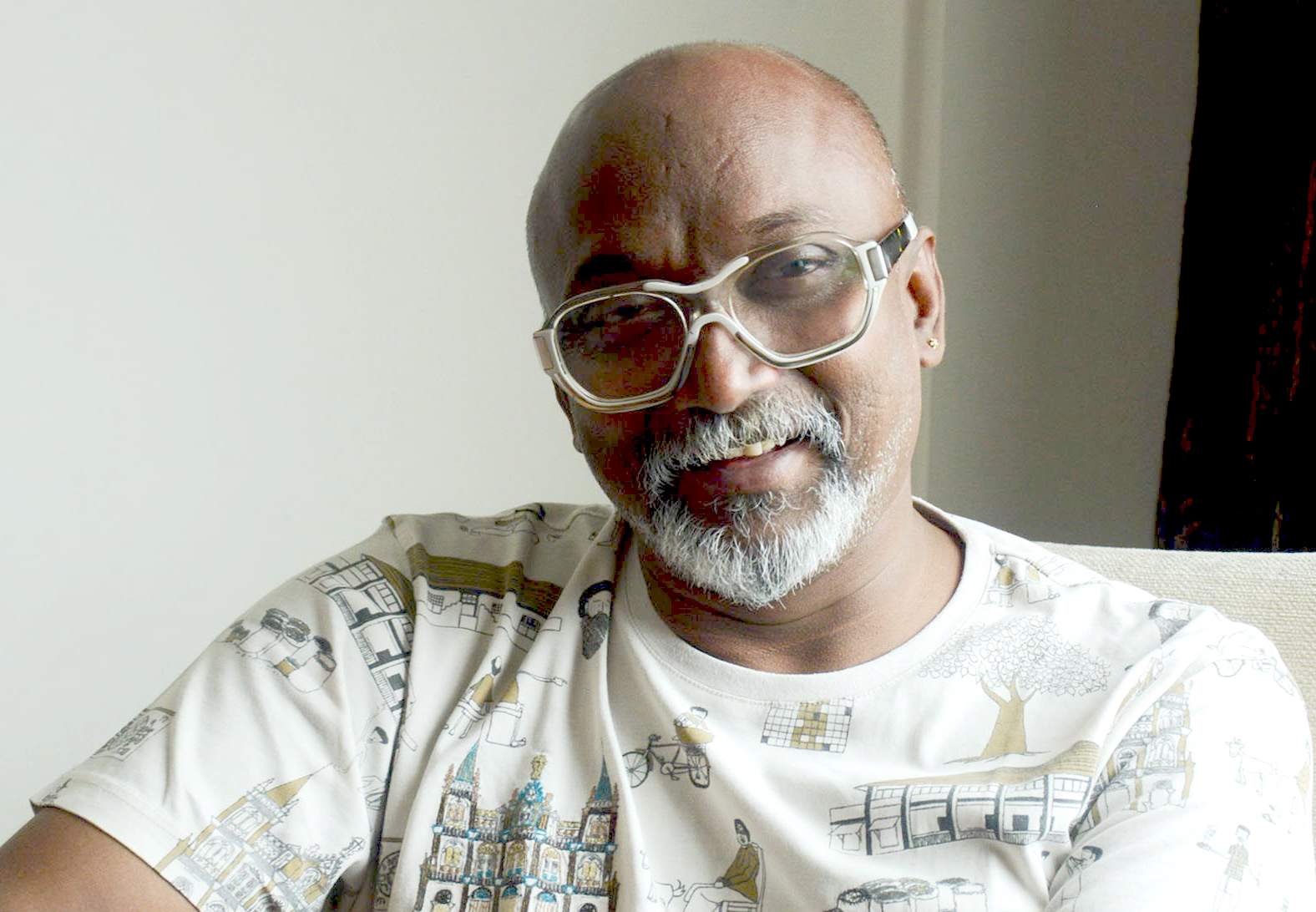

Artist and Curator Bose Krishnamachari.

Synopsis: The continuation of the Biennale seems assured, but its direction and intent are open to question. Will it remain true to what it was originally intended to be? Or will it slowly turn into yet another cultural apparatus, well-funded, well-managed, and carefully depoliticised, something closer to a government programme than an artist-led intervention?

When artist-curator Bose Krishnamachari announced his decision to step down as President of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale and as a Trustee of the Kochi Biennale Foundation on Wednesday, 14 January, the question that immediately crossed one’s mind was not about why he was leaving, but what his absence would mean.

One can speculate umpteen reasons — from the personal to the political, from administrative fatigue to financial pressure, from shifting attention away from organising a massive cultural event to tending to a family that needs him more urgently, from the role of an art administrator back to his forte, his art practice.

But can a replacement ensure that the show goes on as before?

The continuation of the Biennale seems assured, but its direction and intent are open to question. Will it remain true to what it was originally intended to be? Or will it slowly turn into yet another cultural apparatus, well-funded, well-managed, and carefully depoliticised, something closer to a government programme than an artist-led intervention?

The Kochi Biennale Foundation was established in 2010, leading to the launch of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in 2012.

The question is not merely about continuity; it is also about authorship, intent, and ideological direction. It is also a question of ownership. For over 15 years, Krishnamachari was not just the President of the Biennale, he was its most visible face, its principal articulator, and in many ways its moral and conceptual anchor.

When confusion arose, all eyes turned to him. When allegations surfaced, all fingers pointed at him. More often than not, he absorbed it all in silence. His exit, therefore, marks not just a change in leadership but the end of a particular way of thinking about contemporary art in India.

In a personal statement, Bose said the decision followed weeks of reflection and discussion and was prompted by personal and family reasons, as well as a desire to return more fully to his artistic practice.

“After 15 years of being deeply committed and involved in building the Foundation and shaping the Biennale from its inception as an artist-led initiative, I felt this was the right moment to step back,” he noted in a measured statement.

Yet, like all carefully worded exits, it leaves room for questions. Is this the full story, or does it also reflect accumulated pressures, ideological differences, and unresolved tensions around the Biennale’s direction? Is it a moment where administrative logic begins to outweigh artistic intent, or are there forces at play that remain difficult to name or locate?

We may never arrive at a clear-cut answer. But the questions, inevitably, persist.

To understand what Krishnamachari brought to the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, one has to look closely at his practice well before 2012. His artistic journey was never confined to producing objects for galleries. From early on, Bose was preoccupied with how meaning is produced, who controls cultural space, and how institutions frame art.

An exhibition like Double-Enders (comprising works by a host of artists from Kerala) offers an early insight into this thinking. Conceived at a time when Krishnamachari was critically engaging with fixed identities and singular narratives, the exhibition resisted linear interpretation.

The title itself suggests a refusal of closure, something that functions from both ends, never allowing the comfort of a single reading. Here, Krishnamachari explored in-betweenness, between cultures, histories, geographies, visual languages, and ideological positions. Double-Enders also played a significant role in positioning Malayali artists more assertively within contemporary discourse.

Formally, Double-Enders signalled a shift in Krishnamachari’s approach, bringing together different visual modes within a single space. The works resisted easy interpretation and did not settle into a single narrative. Instead, they encouraged viewers to move back and forth, both physically and mentally, and to arrive at meaning through engagement rather than instruction.

In hindsight, Double-Enders can be seen as a bridge between Krishnamachari as an artist and him as a cultural thinker, marking a transition from making artworks to questioning how art is encountered and understood.

What remained unresolved in Double-Enders, and what would soon become central to Krishnamachari’s practice, was the question of scale and access. If meaning is produced through participation, where does that participation take place? Who is allowed to enter the space of art, and on what terms?

That unresolved question found its first concrete response in LaVA, the Laboratory of Visual Arts, initiated in 2005. With LaVA, Bose made a decisive shift from producing objects to building platforms. Conceived as a travelling archive and open reading room, LaVA foregrounded access to knowledge rather than its display. Art was no longer something to be viewed from a distance, but something to be entered, handled, read, and negotiated.

If Double-Enders challenged the authority of the image, LaVA challenged the authority of the institution. Books placed at eye level, or sometimes at ground level, subverted the reverence usually accorded to art knowledge. Temporariness, circulation, and openness became its defining principles. Knowledge was not curated into a fixed narrative, but left deliberately porous.

The project emerged from a simple yet powerful observation: books sold on the pavements of Mumbai, knowledge literally placed on the ground. Krishnamachari transformed this into a critique of elite cultural institutions that treat knowledge as something to be guarded rather than shared. LaVA asked fundamental questions that would later echo through the Biennale. Who controls knowledge? Who has access to it? Where does art begin and end?

LaVA housed books, catalogues, videos, and printed material related to contemporary art. Viewers were invited to read, handle, and engage. The distance between artwork, archive, and audience collapsed. When LaVA found a permanent home at Pepper House in Fort Kochi, it quietly became part of the intellectual groundwork on which the Biennale would later stand. In retrospect, LaVA appears as a proto-Biennale project, artist-led, pedagogical, public-facing, and deeply suspicious of closed systems.

Seen together, Double-Enders and LaVA form a quiet but decisive prelude to the Kochi-Muziris Biennale. One destabilised meaning within the artwork. The other destabilised access to art itself. Both questioned hierarchy, authorship, and enclosure. Both insisted that art must move, across bodies, spaces, and social boundaries.

The Biennale would later scale up these ideas to the level of the city, transforming Kochi itself into an open, participatory site of encounter. In that sense, the Biennale did not arrive as a rupture. It emerged as an expansion of questions first asked in the studio and the reading room, long before they occupied warehouses, streets, and heritage buildings.

The Kochi Biennale Foundation was established in 2010, leading to the launch of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in 2012. Conceived by Krishnamachari along with artist and curator Riyas Komu, the Biennale did not emerge from state policy or corporate ambition. It emerged from an artistic conviction that India needed a platform where contemporary art could engage the public without being filtered entirely through the market or the museum.

Biennale emerged from an artistic conviction that India needed a platform where contemporary art could engage the public without being filtered entirely through the market or the museum.

The choice of Kochi was not accidental. As a historic port city shaped by centuries of exchange, Arab, Chinese, Jewish, and European, Kochi offered a living context rather than a neutral white cube. By invoking Muziris, an ancient port that flourished from the first century BCE, the Biennale situated itself within a longer history of cosmopolitanism that predates colonial modernity.

Equally significant was the decision to use heritage buildings, godowns, and streets as exhibition spaces. This was not merely a logistical choice. It was an ideological one. It rejected exclusivity and embraced permeability. Art entered public life, and the city itself became a collaborator.

Under Krishnamachari’s leadership, the Biennale evolved into the biggest art event in India, fundamentally redefining Fort Kochi. Urban regeneration, the growth of a cultural economy, and the emergence of independent galleries and residencies followed. One may agree or disagree with the Biennale’s curatorial choices, but its impact on the Indian art landscape is undeniable.

Government support was significant, but never singular. The Biennale functioned through a hybrid model, public funding, sponsorship, philanthropy, and community participation, ensuring that it was never fully absorbed into bureaucratic logic. This balance, however, was always fragile.

When the pandemic forced the postponement of the Biennale, a vacuum emerged, economic, psychological, and cultural. Lokame Tharavadu, meaning The World Is One Family, was Krishnamachari’s response to that vacuum. He created a platform for artists across Kerala.

Organised by the Kochi Biennale Foundation in Alappuzha with the support of the Government of Kerala, the exhibition brought together 267 artists, presenting nearly 3,000 works across media. Over 260 temporary galleries transformed godowns into a dense cultural landscape.

The title, drawn from Vallathol Narayana Menon, carried a secular and humanist resonance. At a time of deep social fragmentation, the exhibition asserted shared belonging. Hierarchies were deliberately flattened. Celebrity, market value, and medium were secondary. Each artist was given space, dignity, and visibility.

More than a curatorial project, Lokame Tharavadu was an act of care. Krishnamachari’s travels across Kerala, visiting studios and understanding artists’ conditions, shaped its ethos. It reinforced confidence within a community bruised by crisis and uncertainty.

Though the Biennale functioned through a large team, Krishnamachari remained its most recognisable face. This visibility was both strength and vulnerability. Criticisms targeting the Foundation and Krishnamachari personally were inevitable. Some critiques, particularly those addressing curatorial approaches and contemporary art practices, were valid and necessary, capable of fine-tuning its trajectory and politics. Others were malicious, personalised, and rooted in hostility rather than debate. Such narratives continue to circulate. Tomorrow, more stories may emerge. One cannot deny the possibility of many cans of worms being opened.

Yet, the stress of sustaining an institution of this scale, negotiating with multiple stakeholders while protecting its autonomy, should not be underestimated. A biennale of this magnitude can never be run like a routine government programme. The moment it becomes one, it loses its soul. The Foundation, therefore, has a huge task ahead, to retain it as a living institution rather than an administrative structure.

With or without Krishnamachari, the Biennale has to survive. Institutions, like corporations, often do survive and even progress after their founders leave. But will it remain an artist-led space of risk and dialogue? Or will it gradually settle into administrative safety?

Krishnamachari’s exit marks the end of a phase, one shaped by artistic conviction rather than managerial logic, whatever the reasons behind his departure may be. His contribution to Indian art lies not only in what he created, but in what he made possible. He expanded the very idea of what an artist could do. That, perhaps, is the most enduring question his departure leaves behind.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).