Taking the commercial route, these movies are not only losing out on the nativity but also have become vehicles of regressive propaganda.

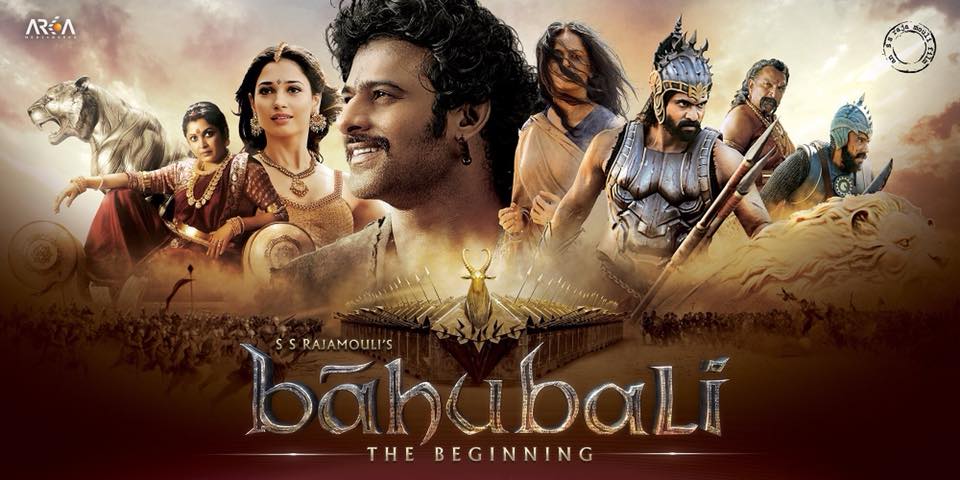

SS Rajamouli's iconic work "Baahubali". (BaahubaliMovie/Facebook)

Business and craft in cinema should complement each other. Dominance of one over the other heavily impacts the output.

A film moves away from the mainstream audience’s sensibility when craft dominates. Similarly, when business looms, the art of cinema struggles to find its space in the product.

So, it is always healthy to ensure the coexistence of commercial factors and artistic nuances in a movie.

In recent years, making a pan-Indian film has become an enviable feat for any film industry in the country.

The story, its emotions, and drama have to travel across borders and cultures to satisfy and connect with an audience who doesn’t speak or understand a film’s original language or value system.

While the idea of “pan-India films” has expanded the business and brought good results for the industry, the art and its sensibilities are at stake.

Making a pan-Indian film isn’t a new idea, to begin with.

When producer SS Vasan made Chandralekha in April 1948, based on The French Bandit in England, his initial intent was to make a film that would entertain the Tamil audience.

However, the success of the Tamil version of the movie gave him the confidence to dub it in Hindi.

KV Reddy’s Mayabazar (1957), an epic fantasy film, is considered a classic in Indian film industry. (Supplied)

Months later, the Hindi version of Chandralekha was released in December 1948 and eventually became the first successful pan-Indian film of independent India.

Many other movies followed in Chandralekha‘s footsteps, such as Maya Bazaar, Naga Devathai, Jaganmohini, and so on.

Producers like LV Prasad, Vittalacharya and AVM were eyeing the Tamil, Telugu and Hindi markets while making any film.

During this era, most of the movies revolved around mythology, horror, or stories of kings and kingdoms.

So the general connective factor was religion or other beliefs of people.

However, from the early 1970s till the early 1990s, there was a significant fall in the number of films being dubbed in any language.

This was when the film industries across the country witnessed the rise of their own exclusive superstars.

Amitabh Bachchan, MGR, Sivaji Ganesan, Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, NTR, Chiranjeevi, Mammootty, Mohanlal, Rajkumar and many others became the icons of their respective languages.

So the stories made with one of these stars in their language would be remade in other languages with actors of similar stardom.

Amitabh Bachchan’s Don (1978) was remade in Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam and even Pakistan-Punjabi with their respective superstars.

That’s one instance of many that followed throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

Since the films were remade in this era, different versions of the same film would be made, suiting the sensibilities and value system of the people of that particular cultural background or the time period.

So the 1980s was full of universal stories with local flavour.

But, in the early 1990s, the idea of pan-Indian films was again revived by filmmaker Mani Ratnam, who made his Tamil film Roja (1992), which was, as well, the debut movie of composer AR Rahman.

Roja created a revolution among the North Indian audiences as it discussed the then ongoing Indo-Pakistan conflicts.

That success gave Mani a boost, and he followed Roja to complete his terror trilogy of films, namely Bombay (1995) and Dil Se (1998).

The success of this trilogy in all the languages they were rereleased inspired South filmmakers like Ram Gopal Varma, Shankar and Kamal Haasan, who ventured into making pan-Indian films like Rangeela, Indian, Hey Ram and so on.

In general, Islamophobia was running through the veins of most of the films in this decade.

Filmmaker Shankar kept up the idea by making all of his films pan-Indian ones, like Jeans, Boys, Anniyan (Aparichit/Aparichithudu), and Enthiran (Robot).

This was when actors who had market value across languages were roped into South films. Aishwarya Rai was part of many pan-Indian films like Enthiran, Guru, and Raavan over the years.

It also continued with stars like Sushmitha Sen, Manisha Koirala, Urmila, Rani Mukherjee, Tabu, Genelia, and Shah Rukh Khan, playing roles in South films.

In this revived era of pan-Indian films, most stories were about patriotism and hyper-nationalism.

There were also sci-fi, comedy, and action films like Aalvandhavaan, Dasavatharam, Vishwaroopam and Mumbai Xpress, all of them written or directed by Kamal Haasan.

During this 2000s era of pan-Indian films, there were too many experiments.

And now, the current era of pan-Indian films, which is commonly referred to as the Baahubali era, is all about larger-than-life cinema.

They’re always about macho protagonists trying to make the impossible possible.

Starting from Baahubali, followed by KGF, 2.0, RRR, Kurup, Vikram, Liger, and so on, the list is full of masculinity-personified characters in this era.

Divided by time and eras, one thing connects all of them — their socio-political incorrectness.

If we observe all these eras, one or the other form of toxicity is affiliated with them.

From glorifying superstitions and false beliefs to fueling hyper-patriotism, misogyny and patriarchy, these films always try to cash in by emotionally manipulating their audiences.

And there’s always only one reason claimed by the makers for this.

When a film is served to a wide range of viewers, satisfying the majoritarian value system is the easy go-to choice of its makers.

A filmmaker like SS Rajamouli, who claims to be an atheist in his real life, has, from time and again, been making pan-Indian films like Eega, Magadheera, Baahubali and RRR, that, in some way or the other, glorify mythology or Hindutva, in particular.

In this lot, Baahubali goes the extra mile to praise Kshatriya dharma, thus acknowledging communal differences and nepotism.

While the second instalment of the KGF franchise has a dialogue against nepotism, if we introspect, KGF would be one of the most misogynistic films ever made in Indian cinema, with a complete male gaze and toxic masculinity.

From the time of films like Don/Billa, we have seen crime lords as protagonists. In those films, those criminals were never worshipped.

But Rocky Bhai of KGF has become a demigod and soon to be a pop-culture icon.

The same goes for Dulquer Salman’s Kurup.

Patriarchy is another element these filmmakers, at least in their films, believe and reiterate. Sye Raa Narasimha Reddy and the upcoming Ponniyin Selvan are a few stories to be put on this list.

However, the most toxic film that romanticised patriarchy on a whole new level is Padmaavat by Sanjay Leela Bhansali.

Yes, it could or could not be based on actual events.

The question is, how relevant is that to the current trends? Why should a film that shows the sick practice of Sati be made in the first place? Even if it was made, at least a social commentary on the same would have made some sense.

Why does Rani Padmaavati fall into the fire? Because if a man other than her husband sees her, it will affect her marital purity or, in other words, “sexual” purity.

So relevant to the 21st century, right?

In a land of diversity, the idea of pan-India has already encroached on regional identities and nativity.

To cater to audiences from different backgrounds, the films take this majoritarian route, painting the characters and value systems in a common shade.

All of KGF: Chapter 2‘s songs are titled in Hindi — Mehabooba, Sultan, and Toofan.

It is from the same industry and soil that resisted Hindi imposition for a long time.

It is not really easy to see a non-Hindu character in the lead role of any pan-India film. But they never fail to propagate Islamophobia.

Just to balance that out, these films will have a good-bad Muslim dichotomy.

Even in this lot, films like The Kashmir Files will top them all by not showing even good Muslims and by just antagonising an entire community.

What can be inferred from all the above instances is that the idea of pan-India is no different from the idea of one nation, one language, and one religion.

The beauty of regional identities and nativities is going to be lost in the plastic identity of one-Indian cinema.

It’s not that all pan-India films are toxic. Let’s take a film like Pink as an example.

It was remade in Tamil as Nerkonda Paarvai and in Telugu as Vakeel Saab, which went on to become huge blockbusters in both languages.

Now let’s reimagine a pan-Indian version of the same film with the three female protagonists played by three leading actresses from three languages and the advocate’s role played by a star from one of the languages or, say, a fourth language.

Now, we have a so-called pan-India film with wide market value, multilingual stars, and vast reach.

Most importantly, it goes against the norm — these types of girls will end up like this only — to knock some sense into the audience’s minds by reiterating ‘No Means No’, in bold.

This film would not have a toxic male in the lead; it would speak of a real social issue, and above all, its relevance will stand the test of time.

So, it’s not difficult to make a pan-India film with real sensibility, isn’t it? And that’s how the art and business of cinema align to create beauty.

World cinema is progressing towards a point where even superhero genre films, which used to have the usual damsel in distress scene, have been revived with the representation of women (Captain Marvel, Wonder Woman), religion (Ms Marvel, Moonknight), race (Black Panther, Shang-Chi) and sexuality (Eternals).

But, Indian films trying to go back in time is not just regression but also very dangerous — time for our cinema to indulge in some introspection.

(The views expressed are personal.)

Jul 24, 2024

Jul 23, 2024

Jul 22, 2024

Jul 19, 2024

Jul 17, 2024

Jul 15, 2024