While the first half is enjoyable and believable, the second half feels disconnected, lacking emotional depth.

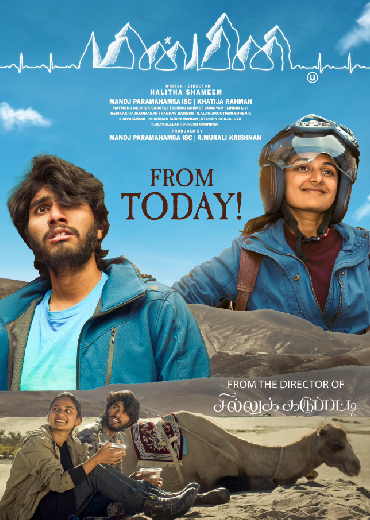

Halitha Shameem's directorial 'Minmini'. (X)

Twenty minutes into Minmini, I realised it was a coming-of-age film. But there is, certainly, more to what meets the eye.

Director Halitha Shameem introduces Paari (Gaurav Kaalai) and Sabari Karthikeyan (Praveen Kishore) to us, at a boarding school in Ooty. Their opposing personalities lead to an initial clash, and they don’t get along.

Paari, an athlete, is adored by everyone, including teachers, who overlook his habit of listening to music during class. In contrast, Sabari is a quiet, studious loner who loves art and excels at chess.

Early in the film, a teacher asks the students about their aspirations. While most answers, like fashion designer or singer, are straightforward, Sabari and Paari’s responses are notably more unusual and don’t fit the mould.

Paari often teases and playfully insults Sabari, and initially, the boys can’t stand each other. Over the following months, Halitha Shameem gradually develops their complex love-hate relationship.

Despite their differences, both Paari and Sabari are caring individuals, who share a love for nature and animals.

Halitha carefully develops their character arcs, clearly showing who they are and the reasons behind their traits.

Although Paari seems rugged, he’s also a softie, a side Sabari never fully sees.

Tragedy strikes when Paari dies, but Sabari later understands that Paari wanted to befriend him. Paari sacrifices his life to save Sabari in an accident, leaving Sabari burdened with guilt upon realising that Paari was the one who saved him.

Paari’s organs are donated to Praveena (Esther Anil), who, eternally grateful, joins the boarding school and learns more about Sabari. She is puzzled by Sabari’s apparent desire to emulate Paari.

Halitha Shameem aims to explore how teenagers confront the weight of survivor’s guilt.

Minmini (the firefly) symbolises positive transience—its season is brief, it shines only in the height of summer, and its light flickers constantly. Paari embodies this firefly—his life was short, but the joy he spread was boundless.

Fireflies, fragile yet stunningly beautiful in large numbers, evoke the essence of adolescence. Like fireflies in a meadow at night, adolescence is delicate and remarkably vibrant.

Seven to eight years later, we see Sabari and Praveena on a bike ride to the Himalayas to fulfil Paari’s dream, driven by their survivor’s guilt. It’s revealed that Praveena intentionally chose to join Sabari, while Sabari barely knows her.

Praveena’s traits symbolise fireflies—hopeful, mindful, and self-aware.

Sabari, like the glowing firefly, too, embarks on a journey of self-reflection and gratitude for what Paari did.

Survivor’s guilt—characterised by feelings of shame or regret from having survived a crisis—can manifest in various ways: discomfort with experiencing joy or positive emotions, remorse over actions or inactions, and persistent questioning of “Why me?” when others did not survive.

This emotional response is common after natural disasters or mass tragedies, even if the survivor is not directly responsible for the event.

The script of Minmini could make an excellent novel. But unfortunately, the emotions don’t fully translate to the screen.

While Halitha Shameem’s attempt to explore survivor’s guilt is commendable, Minmini struggles to connect with the audience. The writing, starting from scratch, feels somewhat convenient and doesn’t resonate.

The issue partly stems from the supporting actors who rely on clichéd expressions. Except for Gaurav Kaalai and Praveen Kishore, the rest of the cast falls short of delivering convincing or natural performances. Esther Anil is somewhat effective in her role.

Shah Ra’s attempt at humour, as the warden, falls flat, due to his inauthentic Malayalam accent.

The teachers, essential for setting the film’s tone, appear artificial, making their performances, unintentionally, comedic. Serious moments are undermined by their exaggerated expressions, shifting the focus from empathy to their lack of authenticity.

For some reason, Minmini feels static, with Halitha Shameem presenting it like a travelogue that misses its mark. The characters only start to open up to each other towards the climax, which makes the ending drag. Esther’s character occasionally reveals details, but this only slows the story’s pace.

It seems Halitha Shameem had too many ideas she wanted to convey and lost her way, unsure of how to end the film.

We see Sabari struggle with guilt as a boy, which is poignant. However, the film doesn’t effectively portray how he manages this guilt as an adult. All we see is him riding a Royal Enfield and being somewhat grumpy, but there’s more to his emotional journey that Halitha Shameem misses exploring.

Sabari and Praveena visit the arts festival, try camel rides, butter tea, and meet fellow bikers. However, as Halitha Shameem portrays in Minmini, real life isn’t as poetic as it appears.

Solo rides are draining and challenging, and soul-searching doesn’t always involve travelling to the Himalayas or connecting with nature. Loneliness persists for survivors, even amidst shared experiences.

#Minmini ✨✨ pic.twitter.com/FKT5Dw7CFX

— Halitha (@halithashameem) August 9, 2024

Survivor’s guilt involves an ongoing internal struggle with a faceless inner judge, without a clear wrong to atone for or a person to make amends to. It’s an intensely personal and internalised emotion.

I wish Halitha Shameem had focused more on these personal conflicts and how the lead characters grappled with them.

I also wish Halitha Shameem had shown how Sabari and Praveena could transform their feelings into a force that propels them forward, rather than being stuck in the past.

Survivor’s guilt attempts to define a feeling that doesn’t fully convey the lived experience. Guilt is constant and doesn’t change day by day; it neither fixes anything nor resurrects the lost. I wish Halitha Shameem had explored these dimensions more deeply.

Additionally, the dialogues in Minmini are overly philosophical. The film’s theme is too heavy for the young actors, and their portrayal of mature activities feels incongruous.

We don’t get detailed insights into their professions; the information is mentioned briefly. Cinema, as we know, is about “showing” rather than just “telling”.

Praveena, who has undergone a heart transplant, is shown travelling alone at high altitudes, putting her health at risk, without any explanation of her preparation or parental permissions.

Similarly, Sabari’s solo ride is depicted without details about his parents’s approval or their background, reducing the credibility of the narrative. These significant oversights weaken the film’s impact.

While the first half of Minmini is enjoyable and believable, the second half feels disconnected, lacking emotional depth and the impact of trauma, turning the film into a series of scenic landscapes and vague Instagram-worthy moments.

However, Manoj Paramahamsa’s cinematography is breathtaking, a true visual feast, complemented by Khatija Rahman’s impressive background score.

The makers of Minmini waited seven years for their child actors to grow up and reprise their roles. While their dedication is clear, the writing needs more substance and engagement beyond its sincere intentions.

You might not mind if an average masala film falls short, but it feels personal when a film aiming for something special doesn’t meet your expectations.

Is Minmini a perfect film? No. But does the director make a significant effort to portray teenage lives, while addressing survivor’s guilt and the importance of living life to the fullest? Yes. But the problem is in how effectively it’s shown.

Minmini, unfortunately, barely scratches the surface of this impactful theme.

(Views expressed here are personal)

(Edited by Y Krishna Jyothi)

(South First is now on WhatsApp and Telegram)

Jan 27, 2026

Jan 17, 2026

Jan 13, 2026

Jan 10, 2026

Jan 09, 2026