Published Jul 25, 2025 | 12:45 PM ⚊ Updated Jul 25, 2025 | 12:45 PM

Hari Hara Veera Mallu is blending politics, policy, and ideology seemlessly

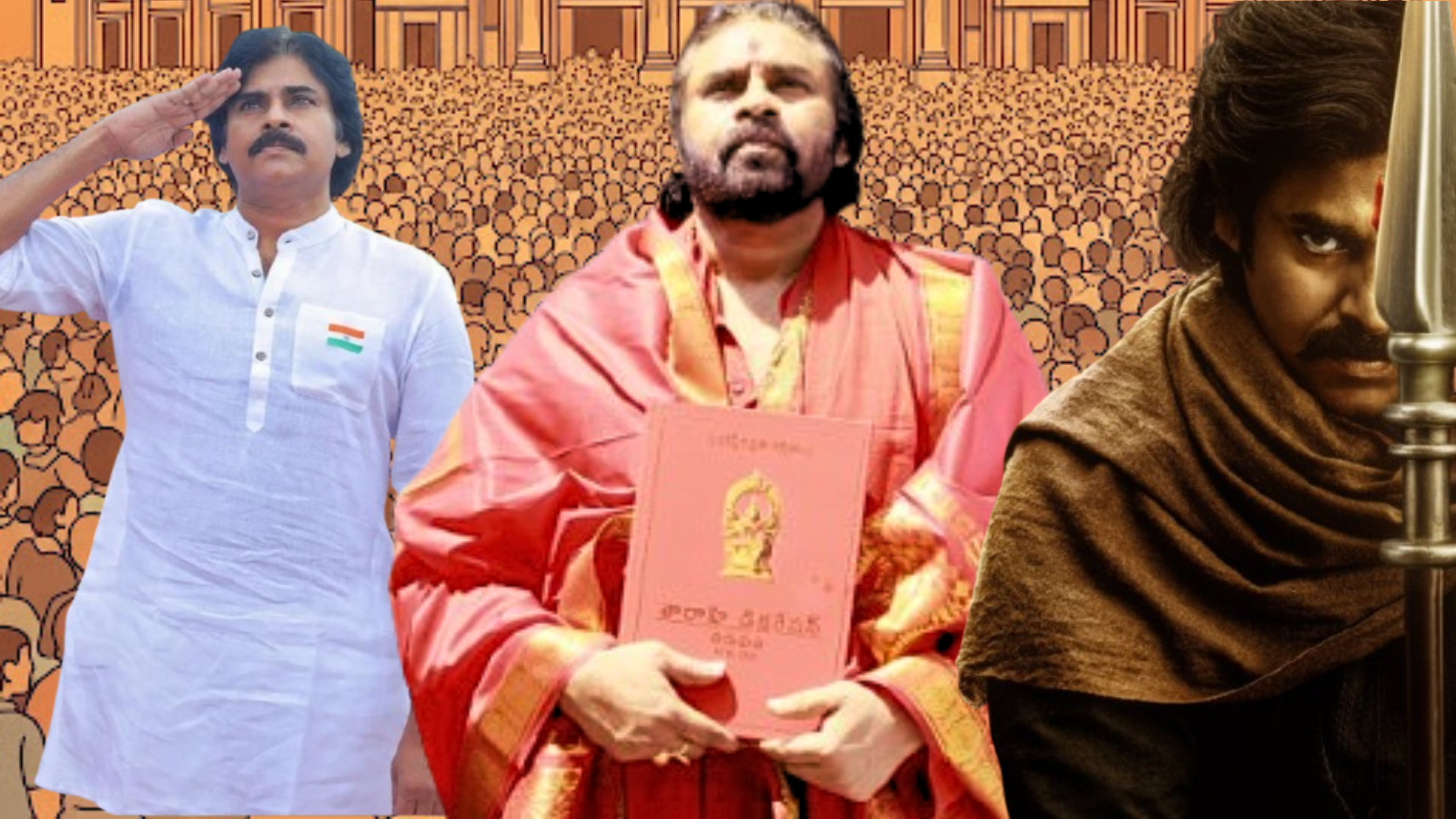

Synopsis: Leaders from Pawan Kalyan’s Jana Sena Party have taken it upon themselves to ensure the film’s commercial success. One leader called it the cadre’s “duty” to support the film, while an MLC reportedly organised mass outings to theatres. The film’s success is being seen, in part, as a test of political strength and symbolic dominance.

Andhra Pradesh Deputy Chief Minister Pawan Kalyan’s latest film, Hari Hara Veera Mallu, released on Thursday, 24 July, is not just a cinematic offering—it is emerging as a political statement.

Set in the Mughal era, the film stars Kalyan as Veera Mallu, a fictional rebel who challenges the Mughal Empire and embarks on a mission to reclaim the Koh-i-Noor.

It’s a story designed to resonate with themes of resistance, Hindu pride, and historical rectification, touching on issues such as the Jizya Tax. However, beyond the story itself, the film appears to serve a dual purpose: to cement Kalyan’s image not only as a mass entertainer but also as a cultural and political figure closely aligned with Hindutva narratives in South India.

While promoting the film on X (formerly Twitter), Kalyan wrote: “The Jizya tax, a punitive levy imposed by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb on Hindus for practising their faith, stands as a stark symbol of oppression, yet historians have long softened its brutality. Hari Hara Veera Mallu boldly unmasks this injustice, exposing the erasure of Hindu suffering and the looting of India’s wealth, like the Kohinoor’s theft. With unwavering resolve, this saga celebrates Sanatana Dharma and the courage of our unsung heroes who defied tyranny.”

The Jizya tax, a punitive levy imposed by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb on Hindus for practicing their faith, stands as a stark symbol of oppression, yet historians have long softened its brutality. #HariHaraVeeraMallu boldly unmasks this injustice, exposing the erasure of Hindu… pic.twitter.com/TiTld0QROP

— Pawan Kalyan (@PawanKalyan) July 24, 2025

Such language signals a clear ideological alignment. Through the film and its promotional discourse, Kalyan is attempting to position himself as the southern torchbearer of Hindutva—someone who is willing to confront the “distorted history” and celebrate Hindu valour against Islamic rulers, a theme that has found electoral resonance in Northern India.

The state administration’s involvement with the film adds another layer to this spectacle. Chief Minister N Chandrababu Naidu, Telugu Desam Party (TDP) supremo and coalition partner of Kalyan’s Jana Sena Party (JSP), extended wishes for the film’s success, expressing hope that it would “captivate all sections of the audience.”

పవన్ కళ్యాణ్ గారి అభిమానులు, ప్రేక్షకులు ఎన్నాళ్ళుగానో ఎదురుచూస్తున్న #HariHaraVeeraMallu చిత్రం విడుదల సందర్భంగా శుభాకాంక్షలు. మిత్రులు పవన్ కళ్యాణ్ గారు… చారిత్రాత్మక కథాంశంతో రూపొందించిన చిత్రంలో తొలిసారి నటించిన ‘హరిహర వీరమల్లు’ సూపర్ హిట్ కావాలని కోరుకుంటున్నాను.… pic.twitter.com/sYHWfoSzg5

— N Chandrababu Naidu (@ncbn) July 23, 2025

Similarly, IT Minister Nara Lokesh tweeted his support, saying: “I too am eagerly waiting for the movie. Pawan Anna, his movies, and his swag are very, very dear to me. I wholeheartedly wish that ‘Hari Hara Veera Mallu‘ achieves tremendous success with Power Star’s powerful performance.”

మా పవన్ అన్న సినిమా #HariHaraVeeraMallu విడుదల సందర్భంగా సినిమా నిర్మాణంలో పాలుపంచుకున్న బృందానికి అభినందనలు. పవర్ స్టార్ అభిమానుల్లాగే నేనూ సినిమా ఎప్పుడెప్పుడా అని ఎదురు చూస్తున్నాను. పవనన్న, ఆయన సినిమాలు, ఆయన స్వాగ్ నాకు చాలా చాలా ఇష్టం. పవర్ స్టార్ పవర్ ఫుల్ పెర్ఫార్మెన్స్తో… pic.twitter.com/NP9rw3eZkR

— Lokesh Nara (@naralokesh) July 23, 2025

However, the blurring of lines between statecraft and cinema promotion has raised eyebrows. Days before the film’s release, the Andhra Pradesh government issued a memo allowing a significant increase in ticket prices—reportedly over 100%—for the first ten days. This boost applies uniformly across cities, towns, and villages. Ironically, this comes just weeks after Kalyan himself advocated for a more affordable cinema experience in the state. The policy contradiction is hard to ignore and has invited criticism about preferential treatment.

The political apparatus surrounding the film goes beyond public endorsements and economic incentives. Leaders from Kalyan’s Jana Sena Party have taken it upon themselves to ensure the film’s commercial success. One leader called it the cadre’s “duty” to support the film, while an MLC reportedly organised mass outings to theatres. The film’s success is being seen, in part, as a test of political strength and symbolic dominance.

Fan activity, too, has intensified in characteristic ways. From violent altercations outside theatres in Machilipatnam and Kadapa to threatening rhetoric against critics in Vijayawada, the frenzy surrounding a Pawan Kalyan film has turned into a spectacle of its own. Such fervour, while not new to Telugu cinema, now exists within a political framework that imbues it with greater consequence.

Adding to the dramatics was the decision to hold a “Success Meet” on the night of the release—an unusual move by industry standards. Speaking at the event in Hyderabad, Kalyan doubled down on the historical and political messaging of the film.

“Many people are still afraid to talk about the atrocities that took place after Aurangzeb’s death. I do not have such fears. I am happy to tell the people about the things that happened in history through the film,” he declared.

He also addressed his critics: “Some of my critics and political opponents are saying that they will boycott my films. I do not care about this at all. Even if I am boycotted, I will not have any problem. The fact that a film I have acted in scares you so much means that we have risen to such a height. I am not someone who is afraid of your slaps. If someone is talking completely negatively about us, it definitely means that we are very strong.”

This rhetoric serves to portray Kalyan as a fearless cultural warrior—one unbothered by elite rejection, bolstered instead by grassroots adoration. In the process, Hari Hara Veera Mallu becomes more than a film; it’s a vehicle for historical revisionism, political projection, and ideological assertion.

The full implications of this experiment—merging mass cinema with state support and Hindutva themes—remain to be seen. But what is evident is that Andhra Pradesh is witnessing the crafting of a new iconography, where the boundaries between screen, state, and saffron are increasingly blurred.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).